This document discusses causality and empirical methods in social sciences. It addresses why causality is an important epistemic norm that shapes how social phenomena are conceptualized and studied. Different views of causality - as something real in the world or as part of statistical models - lead to different modeling approaches. Quantitative and qualitative methods each have strengths and limitations, and combining the two may provide richer insights than either approach alone. Precisely defining and measuring concepts like socioeconomic status is challenging, and larger data sets and more sophisticated tools do not necessarily yield more meaningful results. Causality and choice of methods strongly influence research conclusions.

![Measurement itself, especially if carried out using sophisticated instruments or analysed

using complex methodology, is seen to have the attributes of ‘science’, and often

taken effectively as a justification for believing the results that are presented as

if they have a meaningful relation to whatever social process they are

claimed to measure. […]

New technologies such as powerful dynamic computer graphics do have the potential to

convey findings and patterns in powerful ways, but whether they are used to

inform rather than merely impress, remains an open question.

[…] a better understanding is needed of the difference between data that

‘confirms’ a theory by providing a good model fit, and data that allows

us to explain observed data patterns using as much potentially falsifiable

information as possible.

Harvey Goldstein (2012)

21](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/russo-bamberg-210706151649/85/Causality-and-empirical-methods-in-the-social-sciences-21-320.jpg)

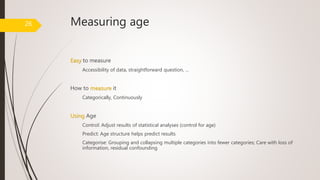

![Why measuring age?

‘Demographic’ age: Locating individuals in the ‘right’ age group

Biological age: A typical health status, for that age

Social age: Social practices that are typical of that age

Epigenetic age: Our internal clock, possibly different from our chronological age

…

[these meanings of age do coincide, possibly they overlap]

Any explanatory import in using age?

27](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/russo-bamberg-210706151649/85/Causality-and-empirical-methods-in-the-social-sciences-27-320.jpg)