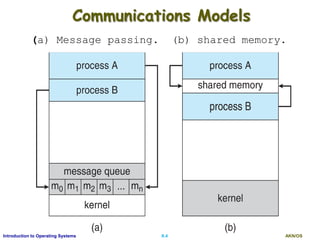

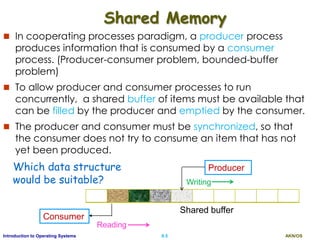

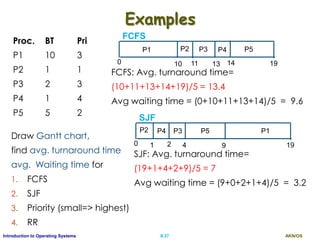

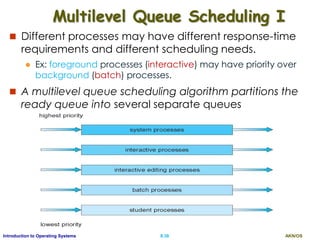

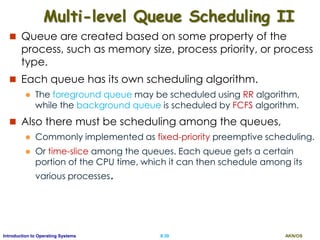

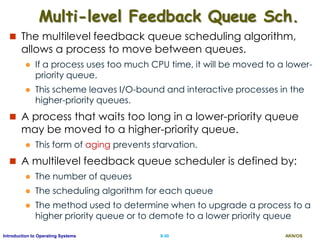

This document discusses interprocess communication and CPU scheduling in operating systems. It covers two models of interprocess communication: shared memory and message passing. It also describes different CPU scheduling algorithms like first-come first-served (FCFS), shortest job first (SJF), priority scheduling, and round-robin. The key aspects of process synchronization, producer-consumer problem, and implementation of message passing are explained.

![AKN/OSII.24Introduction to Operating Systems

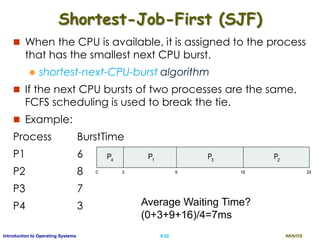

SJF Contd.

SJF can either be preemptive or non- preemptive

Preemptive SJF is known as shortest-remaining-time-first

Example

Proc. A.Time Burst

P1 0 8

P2 1 4

P3 2 9

P4 3 5

P1 P2 P4 P3

0 8 12 17 26

Non-preemptive

P4

0 1 26

P1

P2

10

P3

P1

5 17

Preemptive

Average waiting time for non-preemptive SJF?

[(0-0)+(8-1)+(12-3)+(17-2) ]/ 4 = 7.75ms

Average Waiting time for preemptive SJF?

[(0-0)+(1-1)+(5-3) +(10-1) +(17-2)]/4 = 6.5 ms](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ospartii-170526070622/85/Operating-Systems-Part-II-Process-Scheduling-Synchronisation-Deadlock-24-320.jpg)

![AKN/OSII.25Introduction to Operating Systems

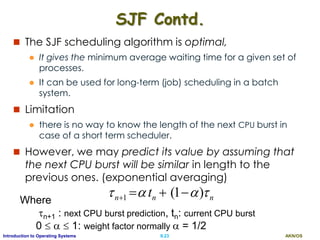

Priority Scheduling

A priority is associated with each process, and the CPU

is allocated to the process with the highest priority.

Equal-priority processes are scheduled in FCFS order.

An SJF algorithm is simply a priority algorithm where the

priority (p) is the inverse of the (predicted) next CPU

burst.

The larger the CPU burst, the lower the priority, and vice versa.

Example (lowest integer is highest priority)

Proc. Burst Priority

P1 10 3

P2 1 1

P3 2 4

P4 1 5

P5 5 2

Average Waiting time?

[0+1+6+16+18]/5 = 8.2 ms

P2 P5 P1 P3 P4

0 1 196 16 18](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ospartii-170526070622/85/Operating-Systems-Part-II-Process-Scheduling-Synchronisation-Deadlock-25-320.jpg)

![AKN/OSII.30Introduction to Operating Systems

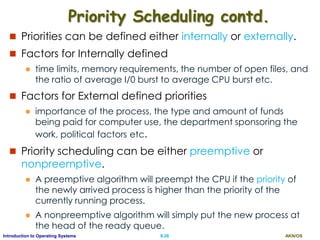

Round-Robin Example with TQ=4

Process Burst

P1 24

P2 3

P3 3

P P P1 1 1

0 18 3026144 7 10 22

P2

P3

P1

P1

P1

Average waiting time?

[(10-4) + 4+ 7]/3 = 5.67ms

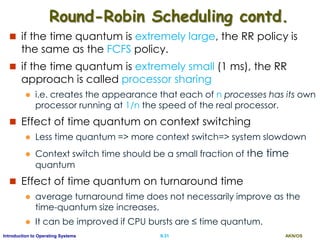

If there are n processes in the ready queue and the time quantum is

q, then each process gets 1/n of the CPU time in chunks of at most q

time units.

Each process must wait no longer than (n - 1) x q time units until its

next time quantum.

Example: Five processes and a time quantum of 20ms.

i.e. each process will get up to 20 milliseconds in every 100ms.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ospartii-170526070622/85/Operating-Systems-Part-II-Process-Scheduling-Synchronisation-Deadlock-30-320.jpg)

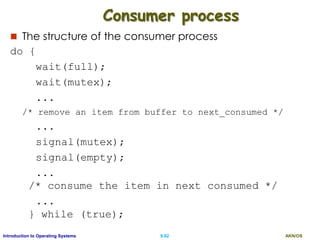

![AKN/OSII.43Introduction to Operating Systems

Producer

while (true) {

/* produce an item in next_produced*/

while (counter == BUFFER_SIZE) ;

/* do nothing */

buffer[in] = next_produced;

in = (in + 1) % BUFFER_SIZE;

counter++;

} while (true) {

while (counter == 0) ;

/* do nothing */

next_consumed = buffer[out];

out = (out + 1) % BUFFER_SIZE;

counter--;

/* consume the item in next_consumed*/

}

Consumer](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ospartii-170526070622/85/Operating-Systems-Part-II-Process-Scheduling-Synchronisation-Deadlock-43-320.jpg)

![AKN/OSII.66Introduction to Operating Systems

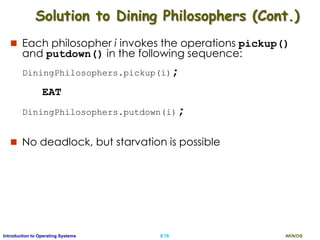

Dining-Philosophers Problem

It is a simple representation of allocating several resources among

several processes in a deadlock-free and starvation-free manner.

represent each chopstick with a semaphore.

Semaphore chopstick [5]

All elements are initialized to 1

Philosophers spend their lives alternating

thinking and eating

Don’t interact with their colleagues, when

hungry, try to pick up 2 chopsticks (one at a

time) that are closest to her

When a hungry philosopher has both her

chopsticks at the same time, she eats.

When she is finished eating, she puts

down both of her chopsticks and starts

thinking again.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ospartii-170526070622/85/Operating-Systems-Part-II-Process-Scheduling-Synchronisation-Deadlock-66-320.jpg)

![AKN/OSII.67Introduction to Operating Systems

The structure of Philosopher i

do {

wait (chopstick[i] );

wait (chopStick[ (i + 1) % 5] );

// eat

signal (chopstick[i] );

signal (chopstick[ (i + 1) % 5] );

// think

} while (TRUE);

Solution guarantees that no two neighbors are eating

simultaneously

But may result in a deadlock

If all five philosophers become hungry simultaneously and each

grabs her left chopstick.

All the elements of chopstick will now be equal to 0. When they

try to grab their right chopstick, they will be delayed forever.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ospartii-170526070622/85/Operating-Systems-Part-II-Process-Scheduling-Synchronisation-Deadlock-67-320.jpg)

![AKN/OSII.76Introduction to Operating Systems

Monitor Solution to Dining Philosophers

monitor DiningPhilosophers {

enum { THINKING; HUNGRY, EATING) state [5] ;

condition self [5];

void pickup (int i) {

state[i] = HUNGRY;

test(i); //makes eating if two chopsticks found

if (state[i] != EATING) self[i].wait;

}

void putdown (int i) {

state[i] = THINKING;

// test left and right neighbors

test((i + 4) % 5);

test((i + 1) % 5);

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ospartii-170526070622/85/Operating-Systems-Part-II-Process-Scheduling-Synchronisation-Deadlock-76-320.jpg)

![AKN/OSII.77Introduction to Operating Systems

Solution to Dining Philosophers (Cont.)

void test (int i) {

if ((state[(i + 4) % 5] != EATING) &&

(state[i] == HUNGRY) &&

(state[(i + 1) % 5] != EATING) ) {

state[i] = EATING ;

self[i].signal () ;

}

}

initializationCode() {

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++)

state[i] = THINKING;

}

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ospartii-170526070622/85/Operating-Systems-Part-II-Process-Scheduling-Synchronisation-Deadlock-77-320.jpg)

![AKN/OSII.97Introduction to Operating Systems

Data Structures for the Banker’s Algorithm

Let n = # of processes, and m = # of resource types

Available: Vector of length m.

If available [ J ] = k, there are k instances of resource type RJ

available

Max: n x m matrix.

If Max [ i, J ] = k, then process Pi may request at most k

instances of resource type RJ

Allocation: n x m matrix.

If Allocation[ i, J ] = k, then Pi is allocated with k instances of RJ

Need: n x m matrix.

If Need[i, J] = k, then Pi may need k more instances of RJ to

complete its task

Need [ i, J ] = Max[ i, J ] – Allocation [ i, J]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ospartii-170526070622/85/Operating-Systems-Part-II-Process-Scheduling-Synchronisation-Deadlock-97-320.jpg)

![AKN/OSII.98Introduction to Operating Systems

Banker’s Safety Algorithm

1. Let Work and Finish be vectors of length m and n,

respectively. Initialize:

Work = Available

Finish [ i ] = false for i = 0, 1, …, n- 1

2. Find an i such that both:

(a) Finish [ i ] = false

(b) Needi Work

If no such i exists, go to step 4

3. Work = Work + Allocationi

Finish[i] = true

go to step 2

4. If Finish [i] == true for all i, then the system is in a safe

state](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ospartii-170526070622/85/Operating-Systems-Part-II-Process-Scheduling-Synchronisation-Deadlock-98-320.jpg)

![AKN/OSII.99Introduction to Operating Systems

Resource-Request Algorithm for Process Pi

Requesti = request vector for Pi.

Requesti [ J ] = k , Pi wants k instances of RJ

Algorithm

1. If Requesti Needi go to step 2.

a) Otherwise, raise error, since it has exceeded its maximum claim

2. If Requesti Available, go to step 3.

a) Otherwise Pi must wait, since resource not available

3. Pretend to allocate requested resources to Pi by modifying

the state as follows:

a) Available = Available – Requesti;

b) Allocationi = Allocationi + Requesti;

c) Needi = Needi – Requesti;

4. If safe the resources are allocated to Pi

a) Otherwise Pi must wait, and the old resource-allocation state is

restored](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ospartii-170526070622/85/Operating-Systems-Part-II-Process-Scheduling-Synchronisation-Deadlock-99-320.jpg)

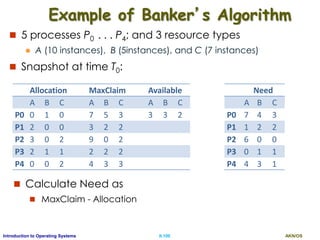

![AKN/OSII.101Introduction to Operating Systems

P1 Request (1,0,2)

Check that Request Available (that is, (1,0,2) (3,3,2) true

So find the new state at time T1

Allocation Need Available

A B C A B C A B C

P0 0 1 0 7 4 3 2 3 0

P1 3 0 2 0 2 0

P2 3 0 2 6 0 0

P3 2 1 1 0 1 1

P4 0 0 2 4 3 1

Now execute safety algorithm and find the safe sequence

1. Work = Available, Finish [ i ] = false for i = 0, 1, 2, 3, 4

2. Find an i such that

Finish [ i ] = false & Needi Work

If no such i exists, go to step 4

3. Work = Work + Allocationi

Finish[i] = true, go to step 2

4. If Finish [i] == true for all i, is in a safe state

Safe sequence is < P1, P3, P4, P0, P2>, so request allowed.

Can request for (3,3,0) by P4 be granted? At T0, if yes then find the

safety sequence

Can request for (0,2,0) by P0 be granted? At T0 , if yes then find

the safety sequence](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ospartii-170526070622/85/Operating-Systems-Part-II-Process-Scheduling-Synchronisation-Deadlock-101-320.jpg)

![AKN/OSII.104Introduction to Operating Systems

Several Instances of a Resource Type

Available:

A vector of length m => the number of available

resources instances

Allocation:

An n x m matrix => the number of resources

instances of each type currently allocated.

Request:

An n x m matrix => the current request of each

process.

If Request [i][J] = k, then process Pi is requesting k

more instances of resource type RJ.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ospartii-170526070622/85/Operating-Systems-Part-II-Process-Scheduling-Synchronisation-Deadlock-104-320.jpg)

![AKN/OSII.105Introduction to Operating Systems

Detection Algorithm

1. Let Work and Finish be vectors of length m and n, initialized as

follows

(a) Work = Available

(b) For i = 1,2, …, n, if Allocationi 0, then

Finish[i] = false; otherwise, Finish[i] = true

2. Find an index i such that:

(a) Finish[i] == false

(b) Requesti Work

If no such i exists, go to step 4

3. Work = Work + Allocationi

Finish[i] = true

go to step 2

4. If Finish[i] == false, for some i, 1 i n, then the system is in

deadlock state.

Moreover, if Finish[i] == false, then Pi is deadlocked

Algorithm requires an order of

O(m x n2) operations to detect

a deadlocked state](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ospartii-170526070622/85/Operating-Systems-Part-II-Process-Scheduling-Synchronisation-Deadlock-105-320.jpg)

![AKN/OSII.106Introduction to Operating Systems

Example of Detection Algorithm

Five processes P0 through P4; three resource types

A (7 instances), B (2 instances), and C (6 instances)

Snapshot at time T0:

Allocation Request Available

A B C A B C A B C

P0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

P1 2 0 0 2 0 2

P2 3 0 3 0 0 0

P3 2 1 1 1 0 0

P4 0 0 2 0 0 2

Find if there is a deadlock?, if no then find the sequence.

Sequence <P0, P2, P3, P1, P4> will result in Finish[i] = true for all i

Suppose P2 requests an additional instance of type C, then find the

system status

i.e. No deadlock => process execution sequence

Deadlock => list of deadlocked process](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ospartii-170526070622/85/Operating-Systems-Part-II-Process-Scheduling-Synchronisation-Deadlock-106-320.jpg)