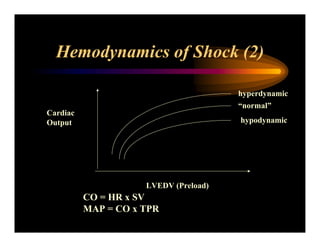

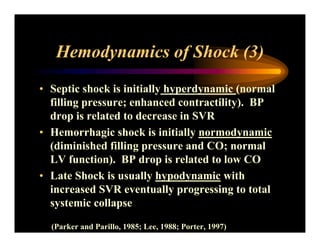

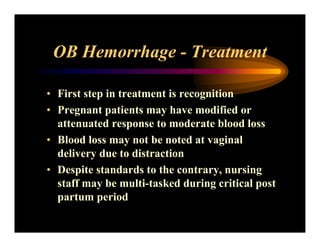

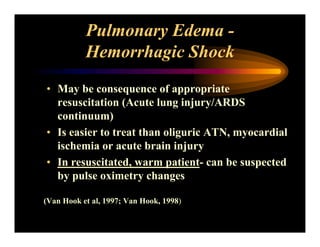

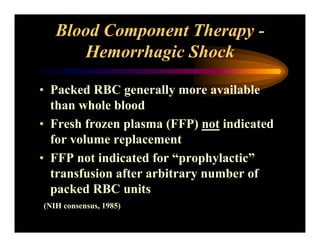

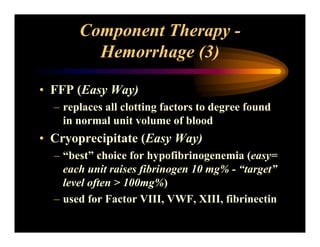

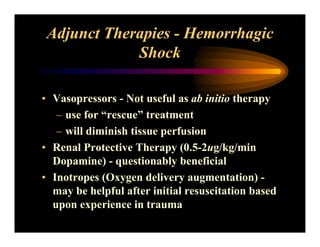

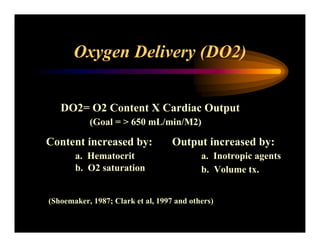

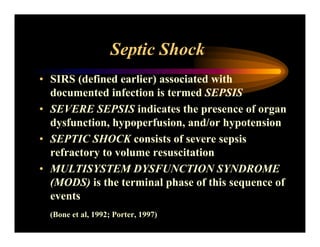

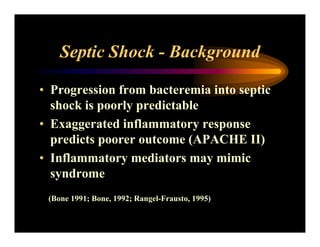

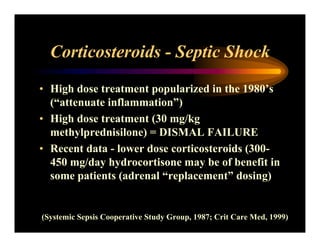

This document discusses obstetric shock, with a focus on hemorrhagic and septic shock. It defines shock and outlines the pathophysiology and continuum of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and shock. It discusses the mediators involved in SIRS and shock like cytokines, nitric oxide, and others. It also covers the hemodynamics of shock and how it can present as hyperdynamic, hypodynamic, or normodynamic. Treatment of hemorrhagic shock through fluid resuscitation and blood component therapy is outlined.