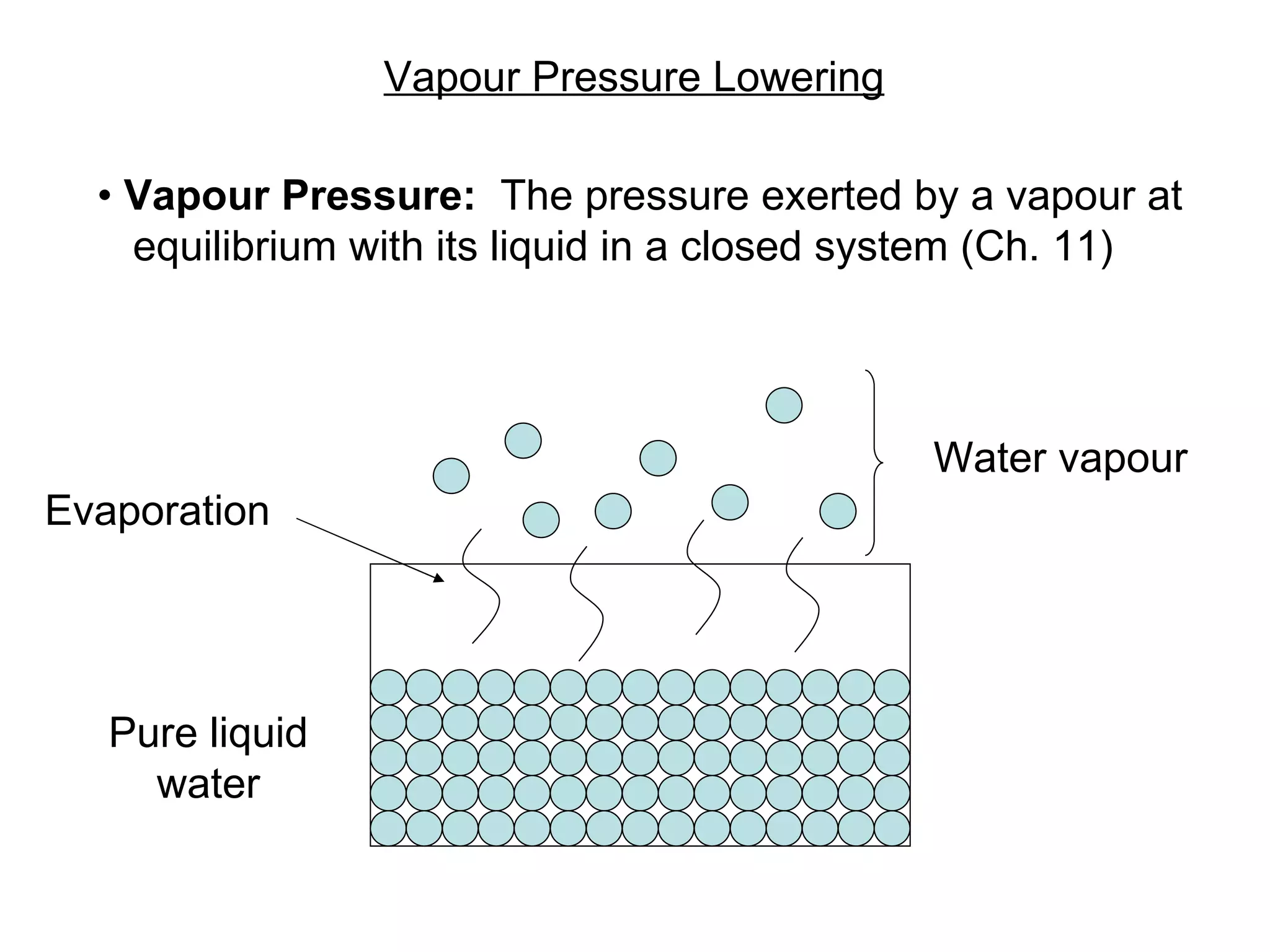

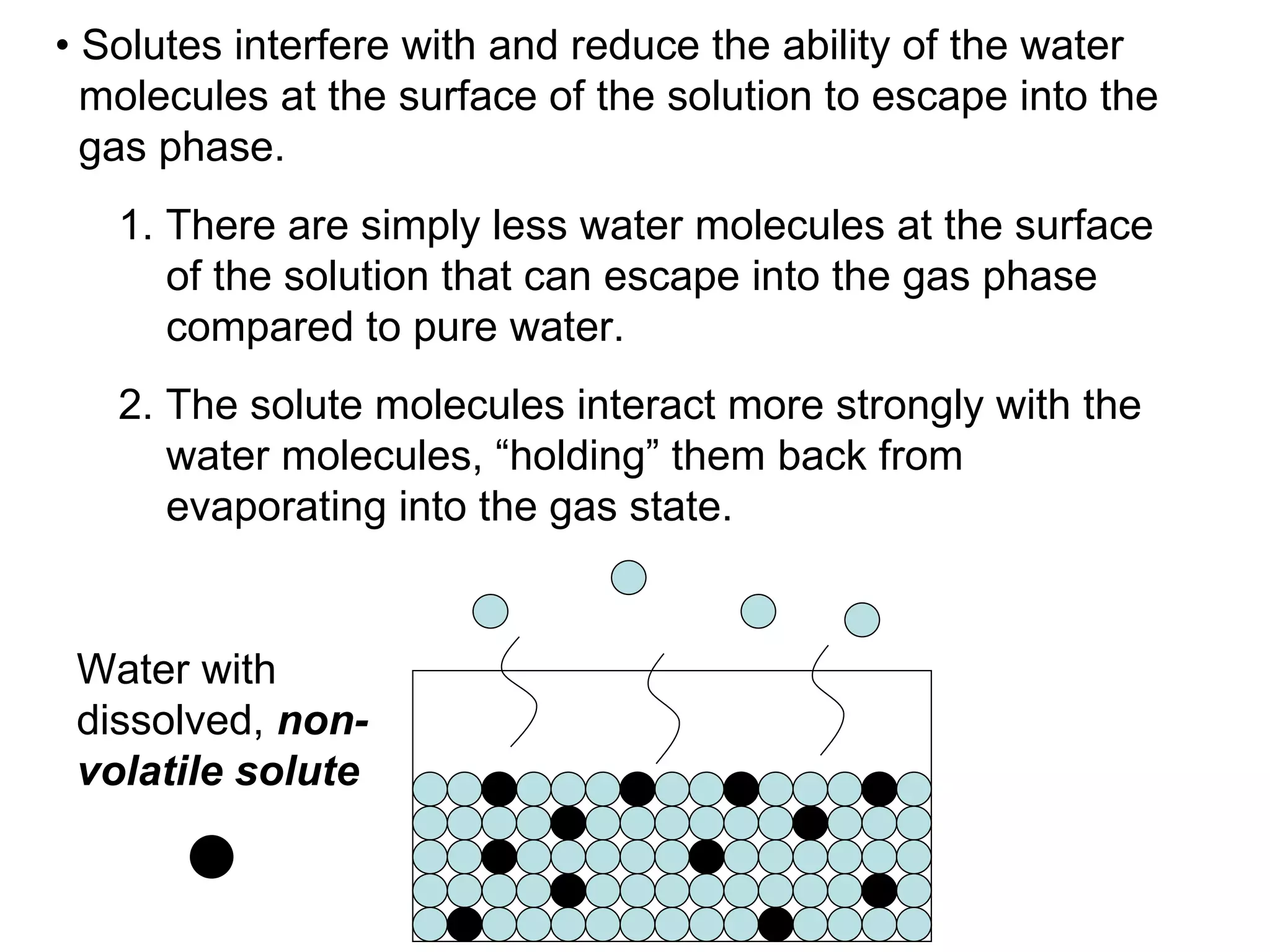

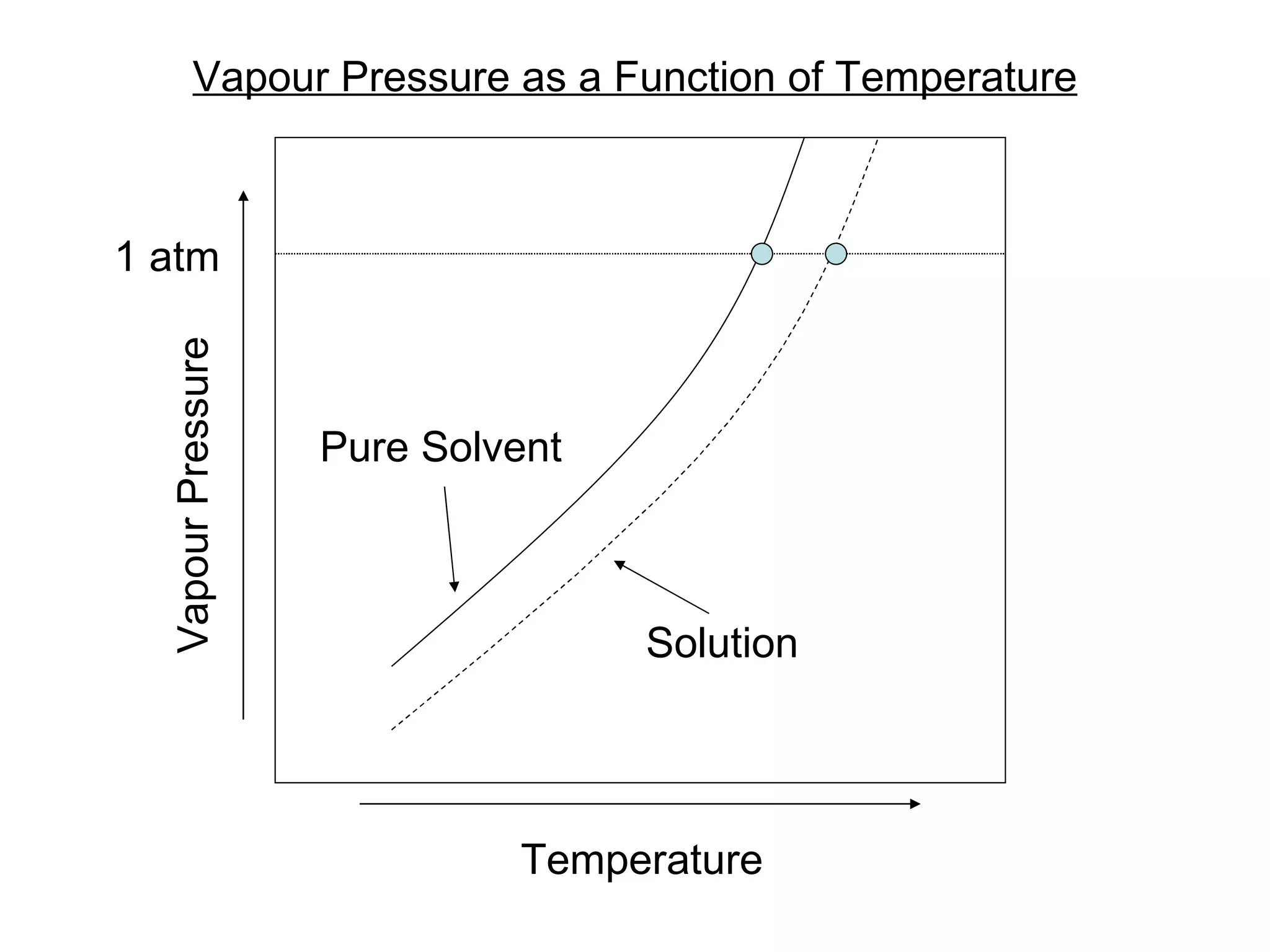

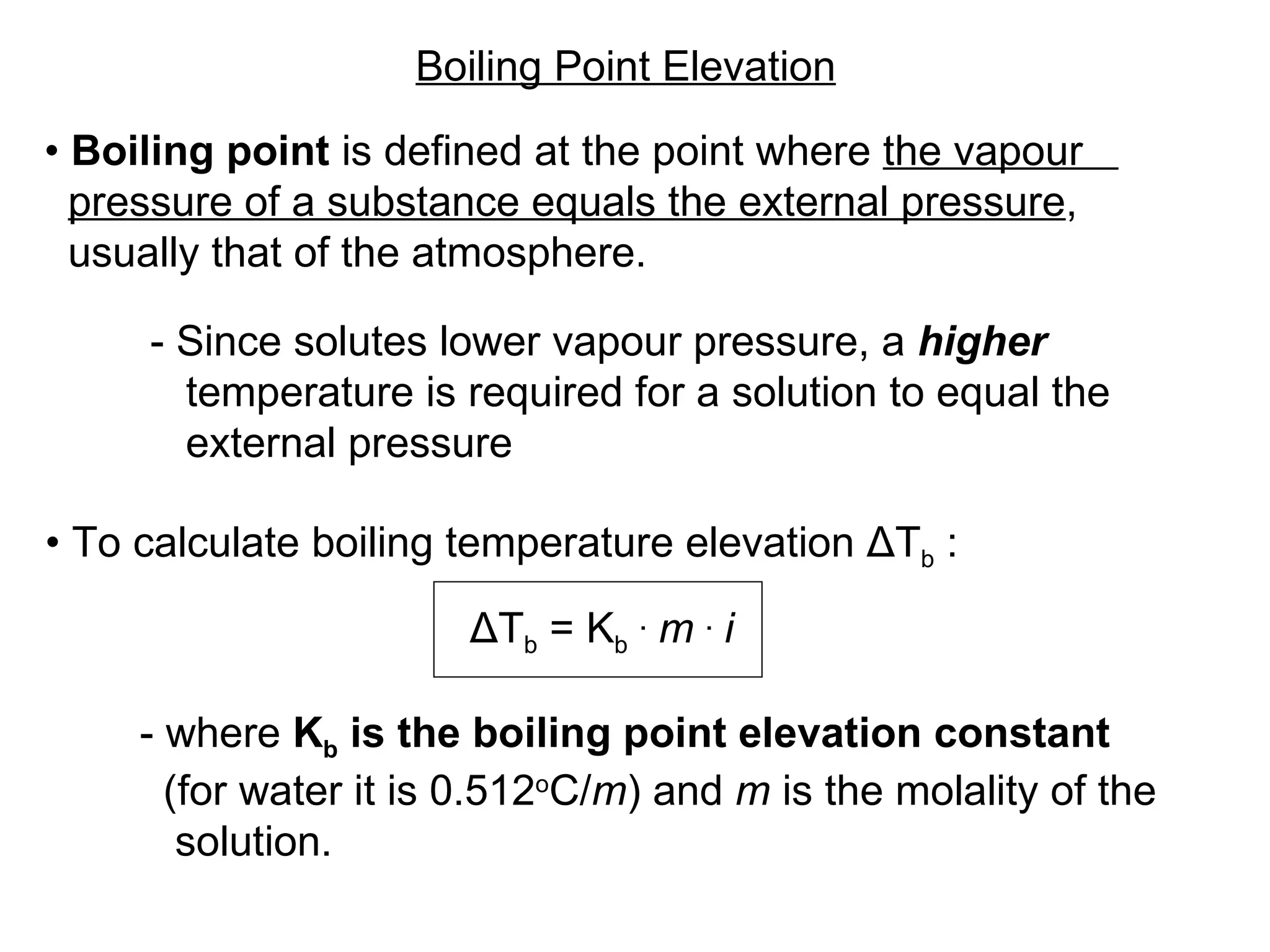

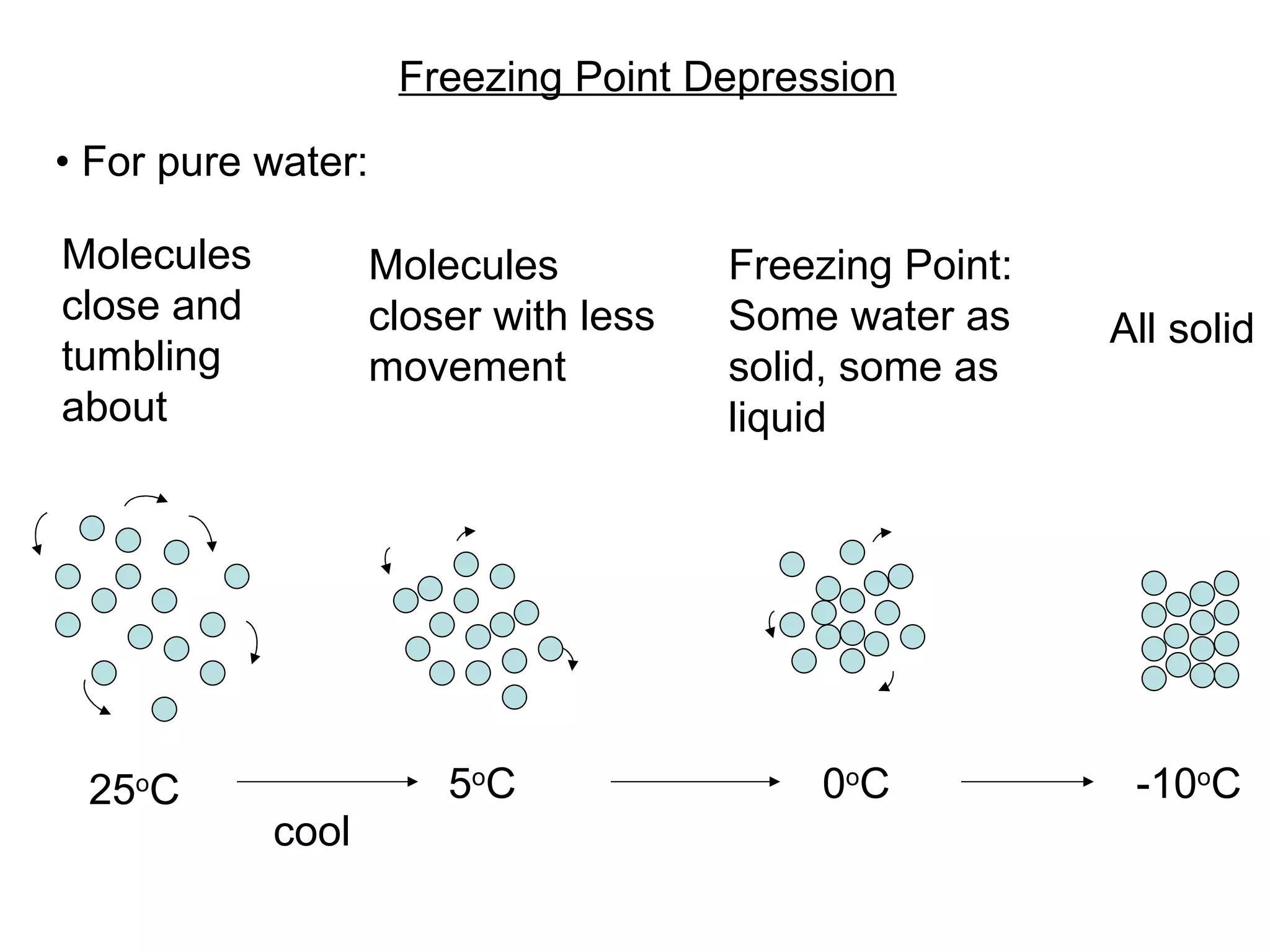

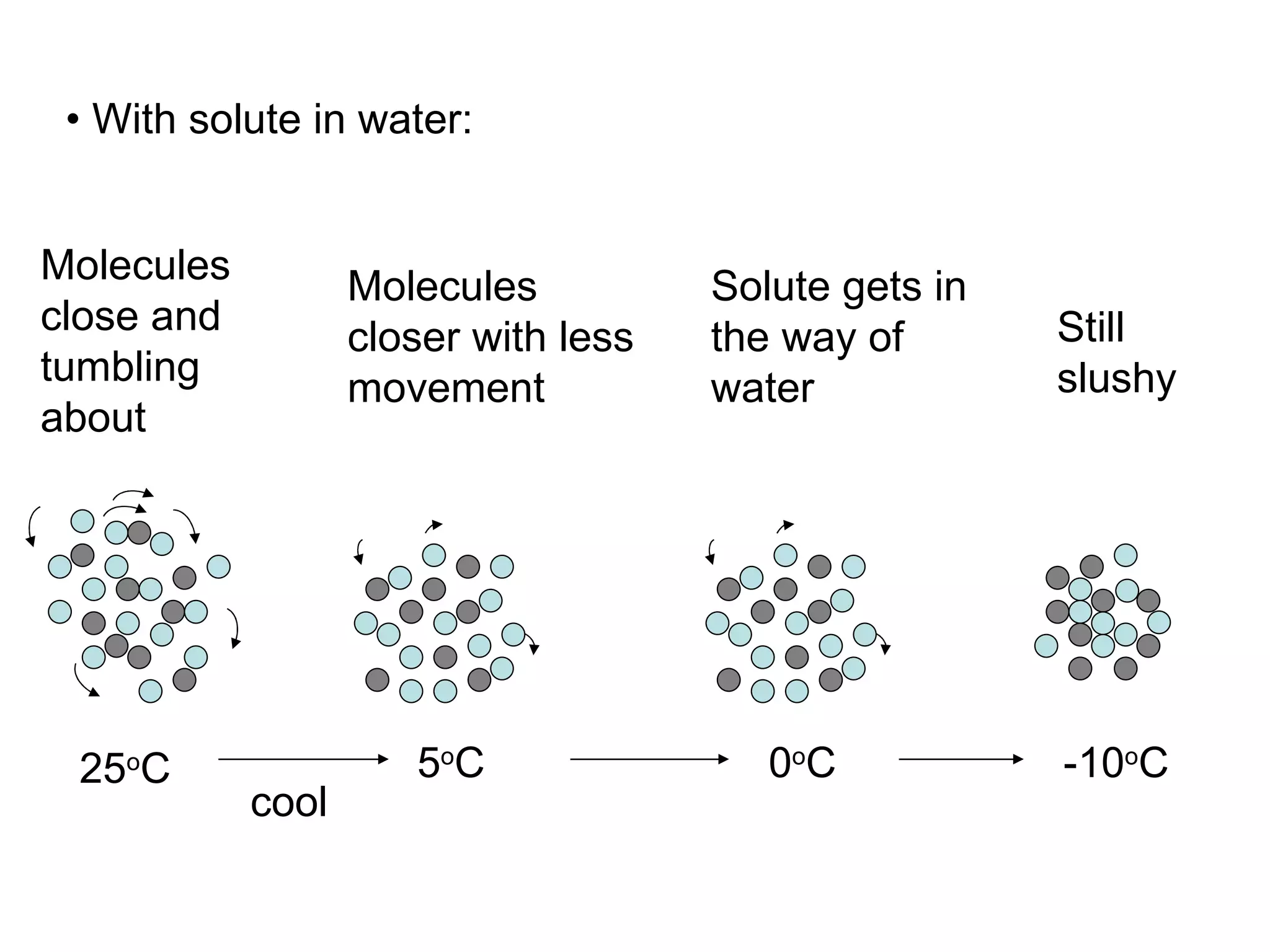

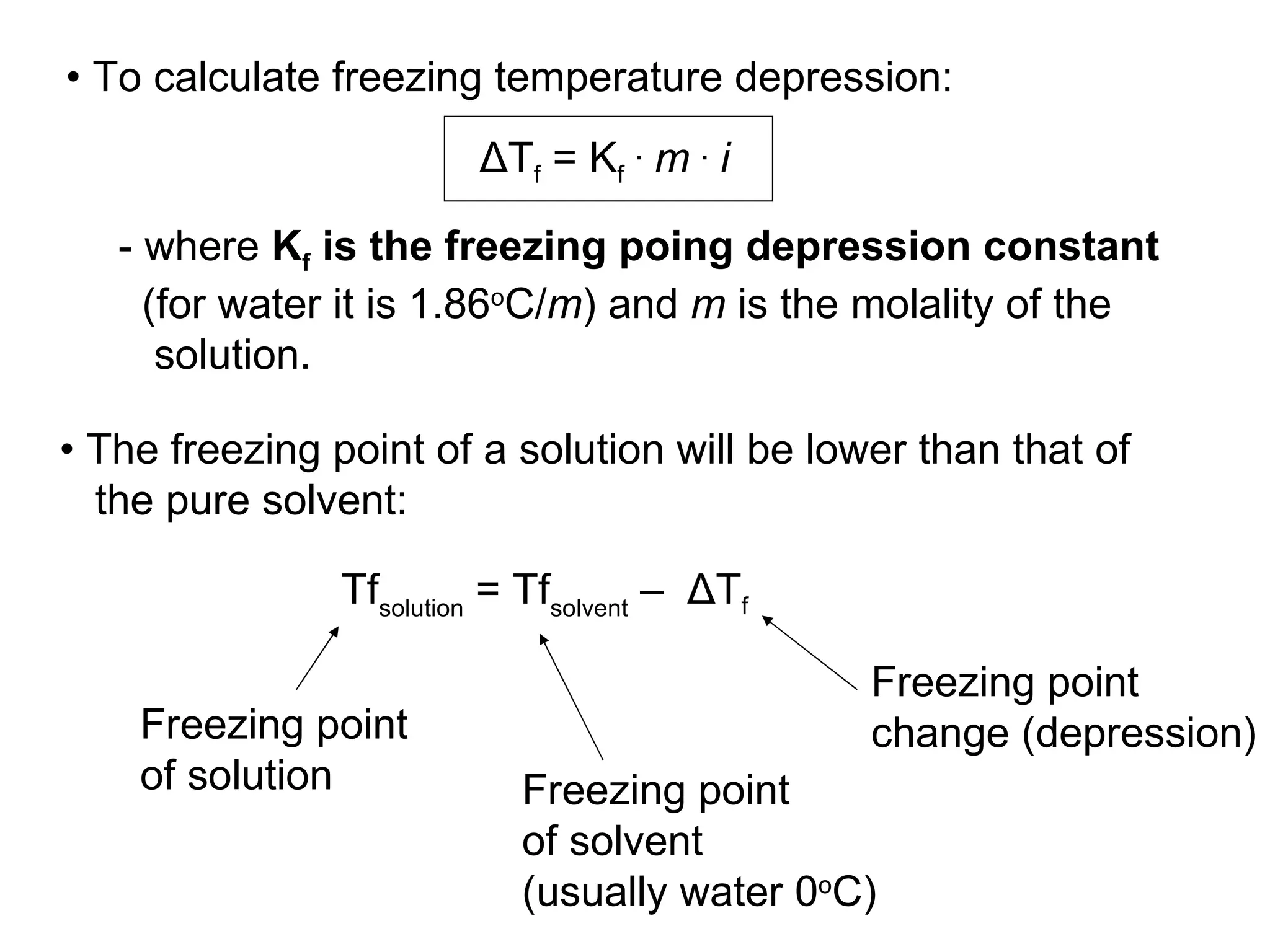

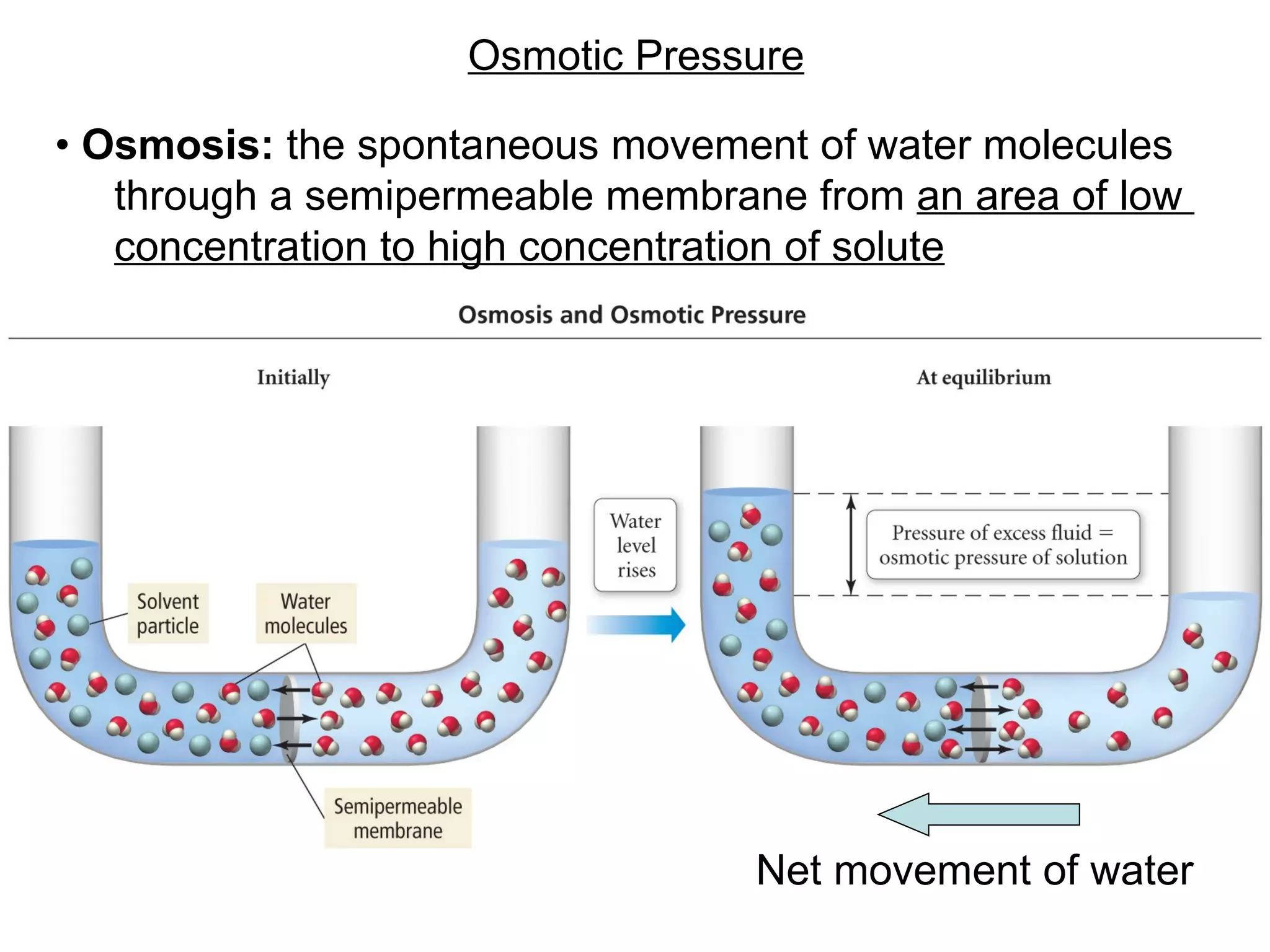

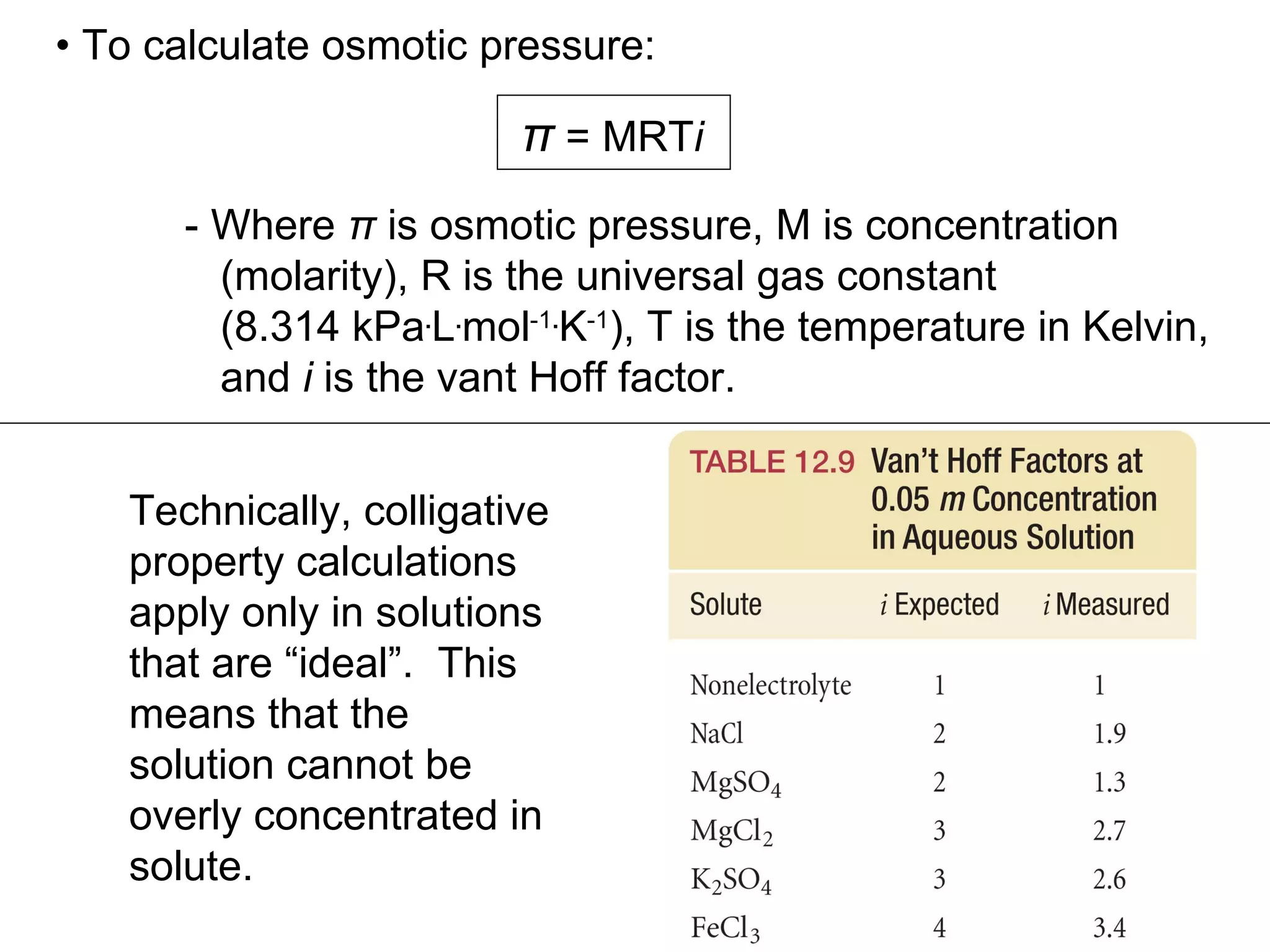

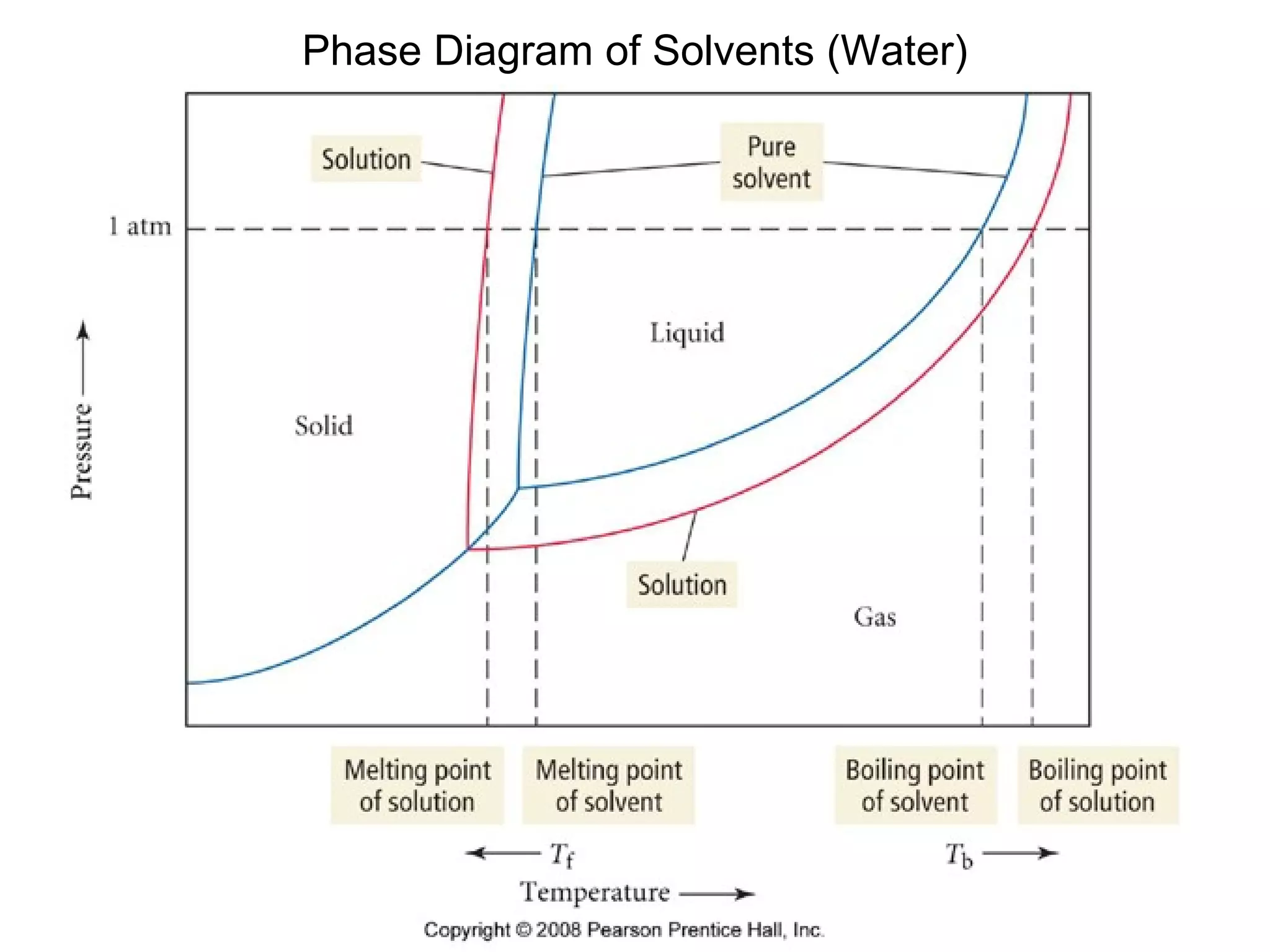

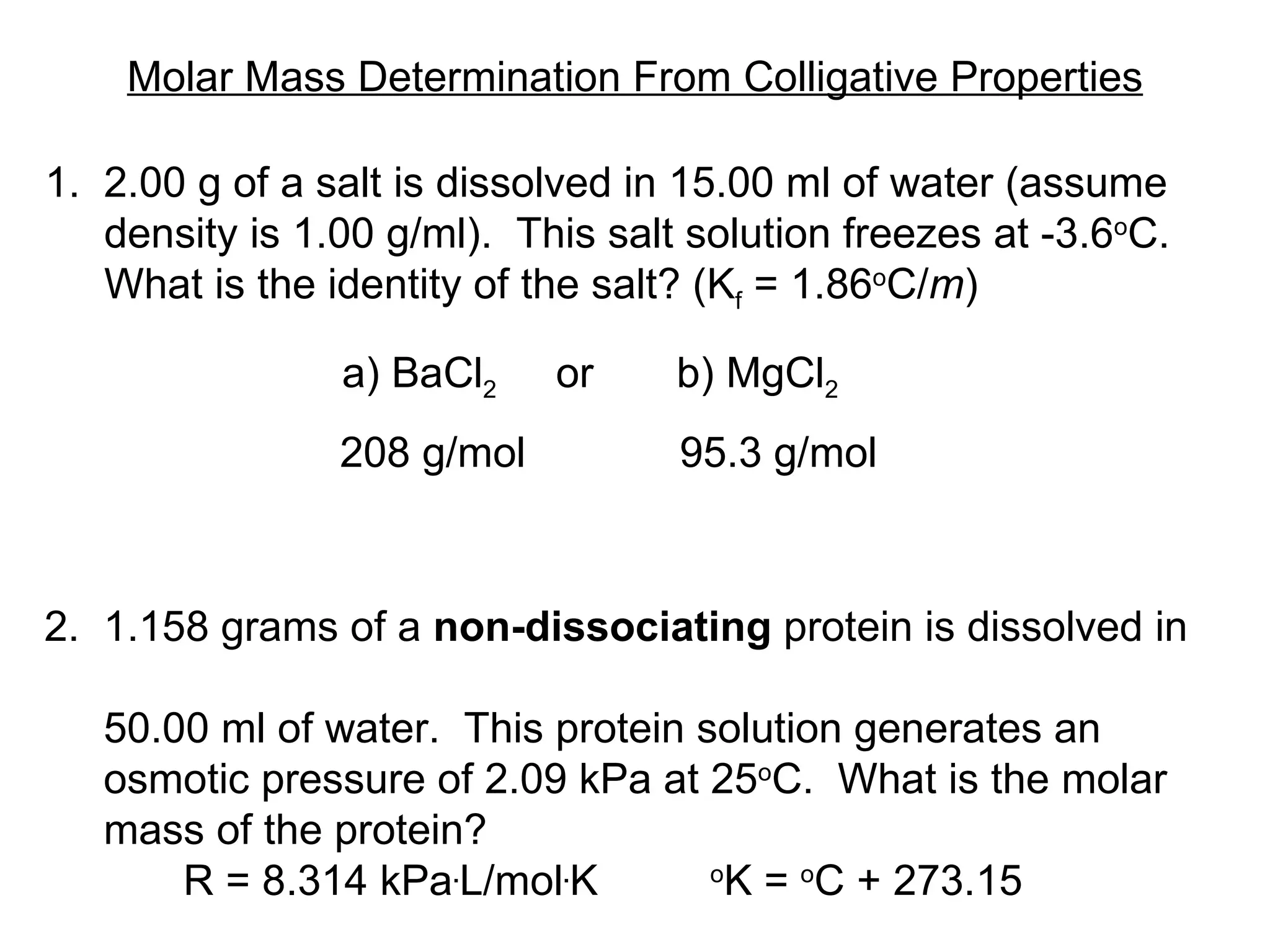

The document discusses colligative properties of solutions, which depend only on the number of solute particles and not their type. It describes how adding solute particles lowers vapor pressure and freezing point and raises boiling point of the solvent. Specifically, it provides equations to calculate boiling point elevation, freezing point depression, and osmotic pressure based on molality and van't Hoff factor of the solution.

![• Expressing Reaction Rate (of Reactants and Products) - Rate is defined as a change in some variable per unit of time. - If we measure the change in concentration of A over time, we can determine its reaction rate. Take the reaction A B = = [ ], square brackets are short-hand notation for concentration Δ [A] Δ t [A] 2 - [A] 1 t 2 – t 1 There is a minus sign since A is disappearing in the reaction change in [A] change in time](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nybf09-unit2slides1-25-100125181432-phpapp01/75/Nyb-F09-Unit-2-Slides-1-25-21-2048.jpg)

![- Alternatively, we could have also measured the rate of change in B. Since B is being produced, its change is positive Reaction A B Finally, in this particular example. Since reactants disappear, the change is negative Since products are produced, the change is positive . Δ [A] Δ t Therefore rate = And is measured in units of M/time ( mol . L -1 . time -1 ) Δ [B] Δ t Δ [A] Δ t =](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nybf09-unit2slides1-25-100125181432-phpapp01/75/Nyb-F09-Unit-2-Slides-1-25-22-2048.jpg)

![• For any general reaction of say a A + b B c C + d D - Where the italicized letter is the stoichiometric coefficient - The rate expression of all reactants and products would be: Rate = Δ [B] Δ t Δ [A] Δ t = Δ [D] Δ t Δ [C] Δ t = 1 a 1 b = 1 c 1 d](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nybf09-unit2slides1-25-100125181432-phpapp01/75/Nyb-F09-Unit-2-Slides-1-25-23-2048.jpg)