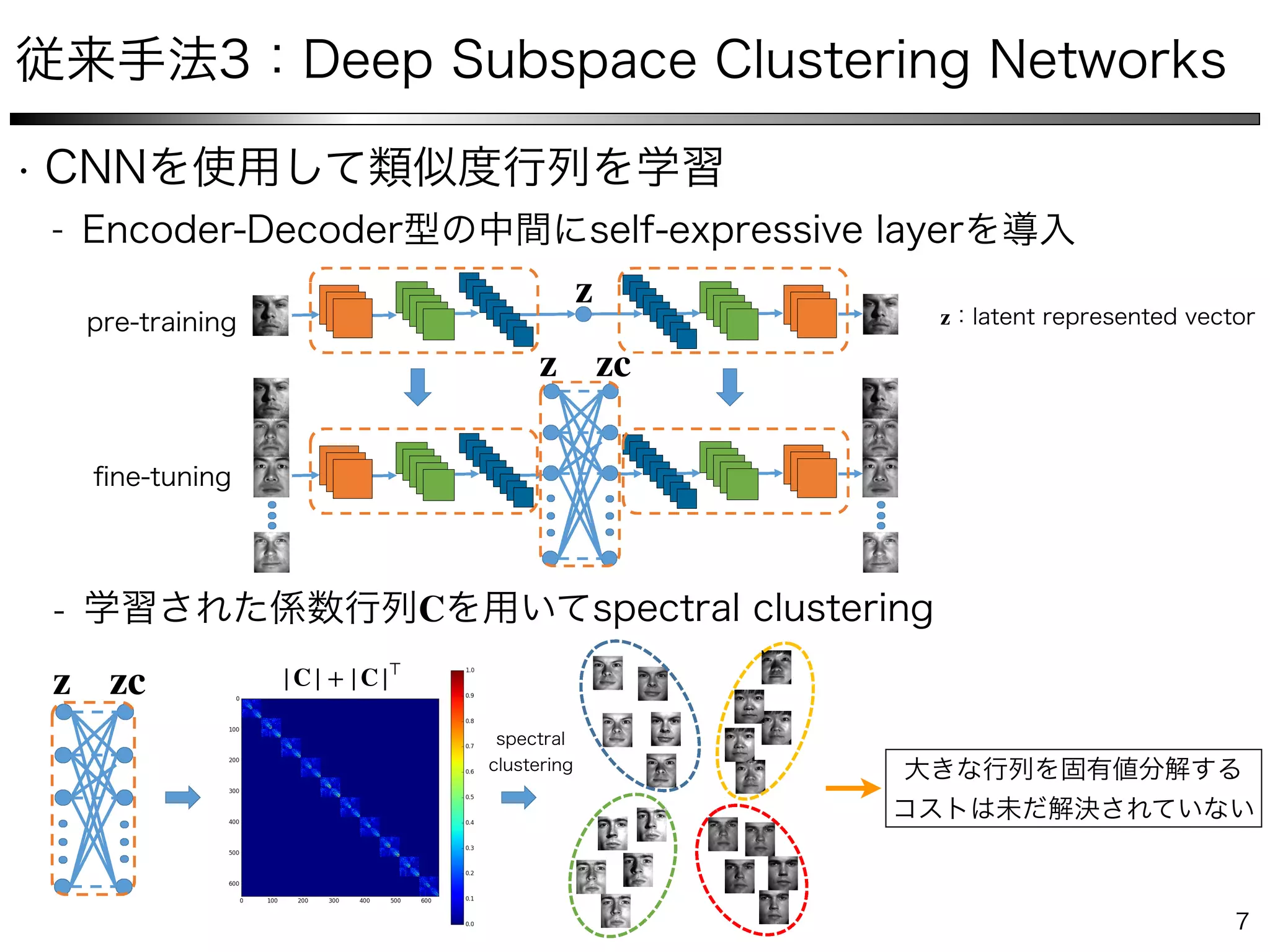

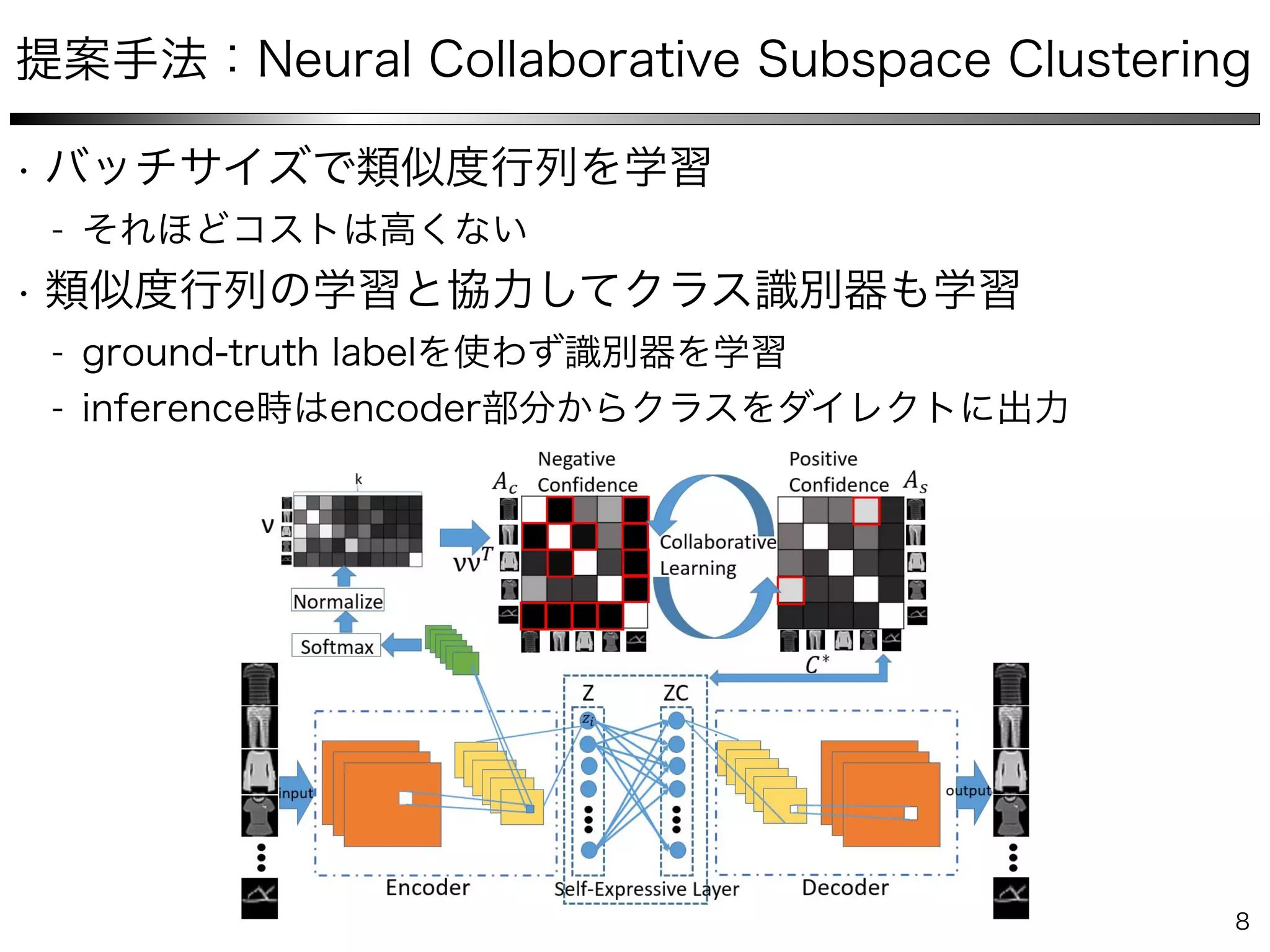

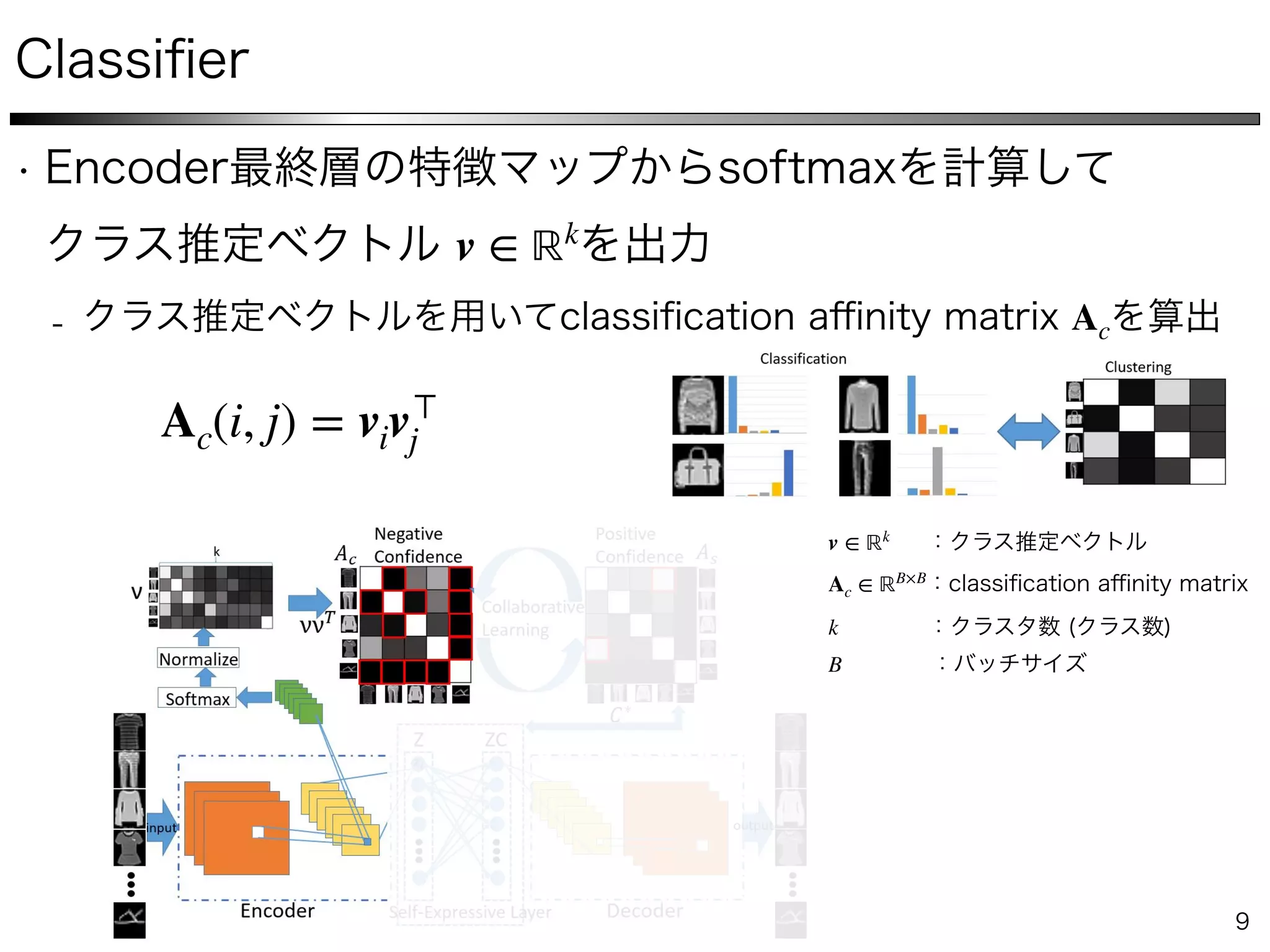

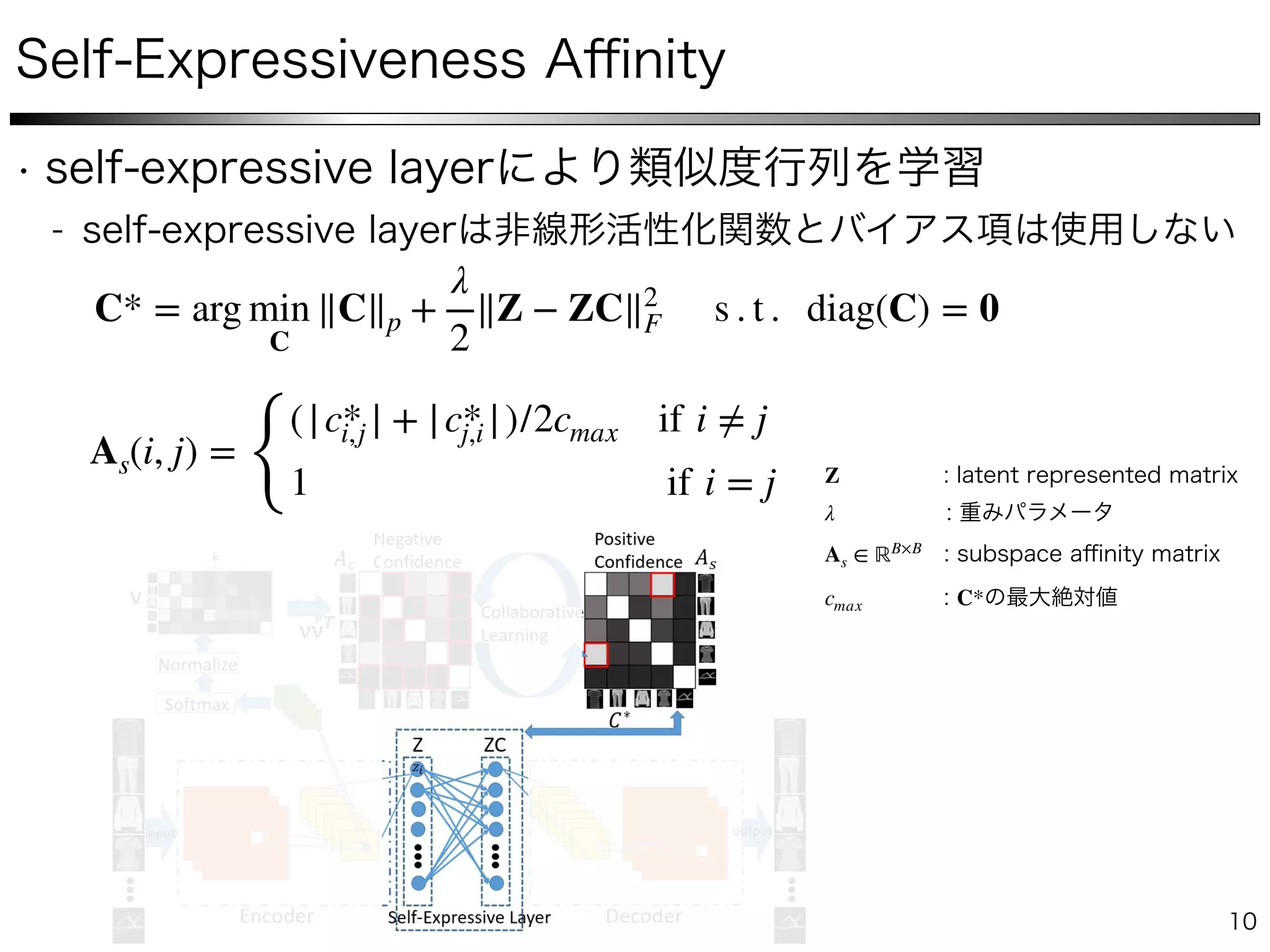

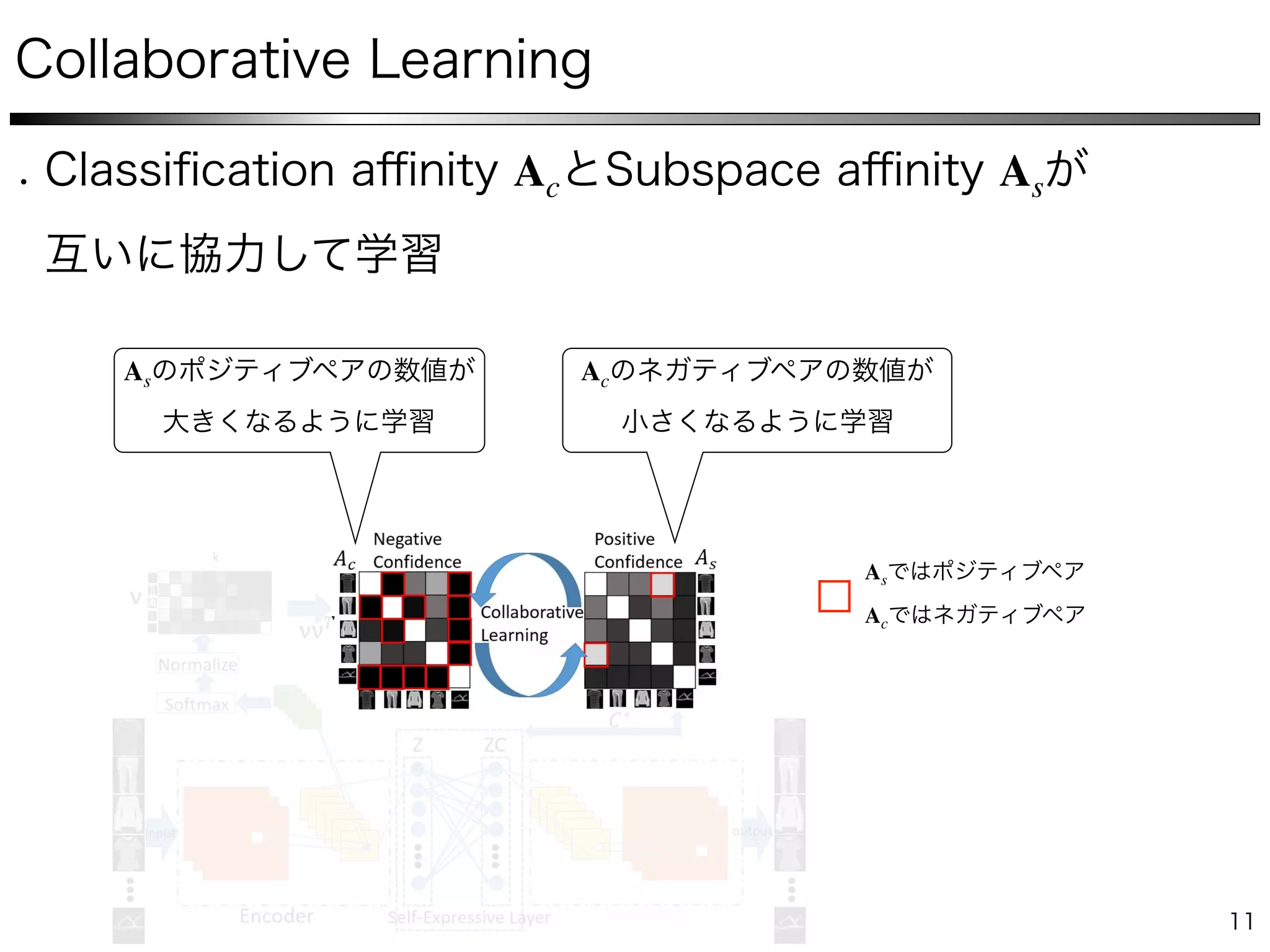

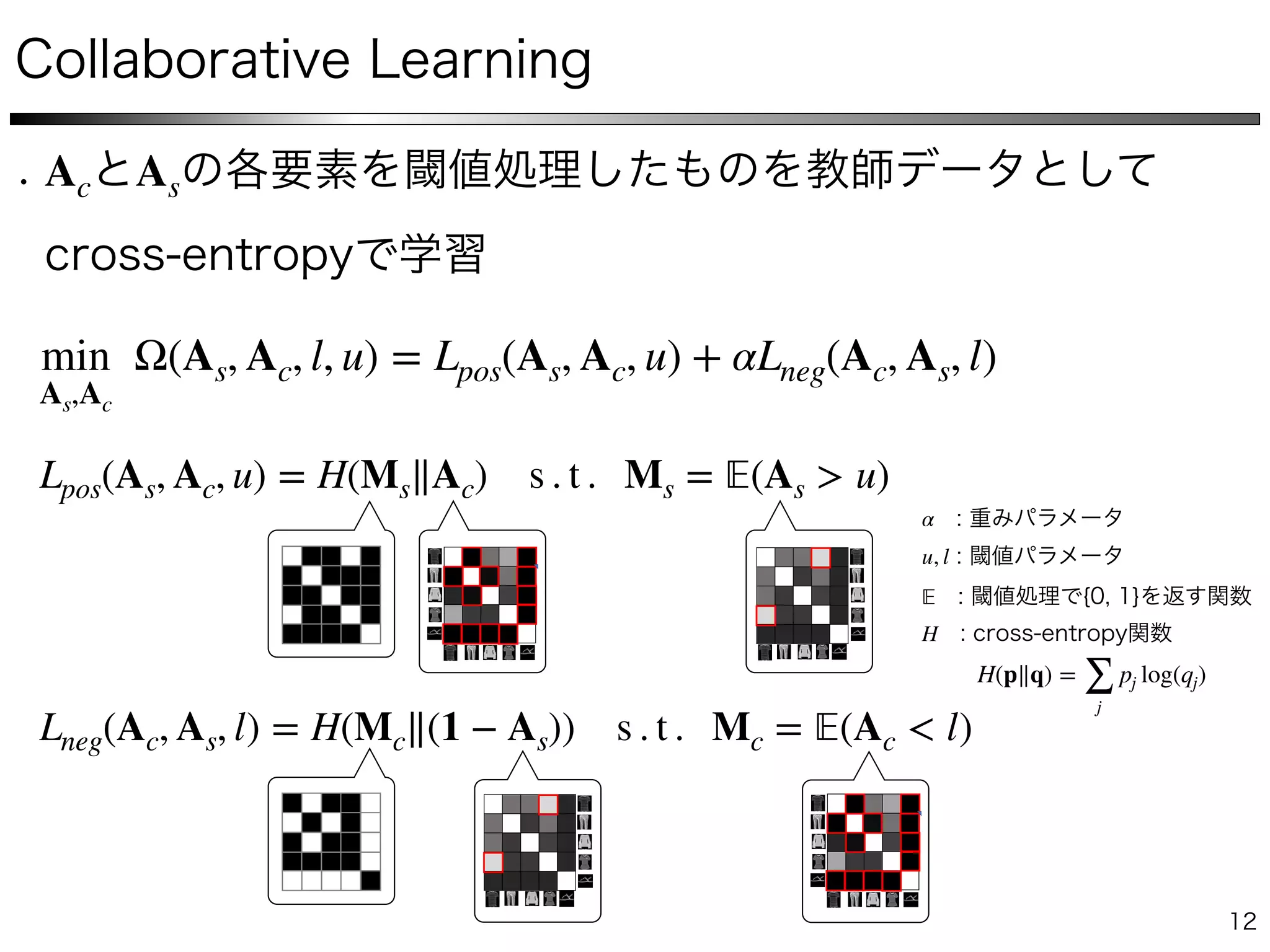

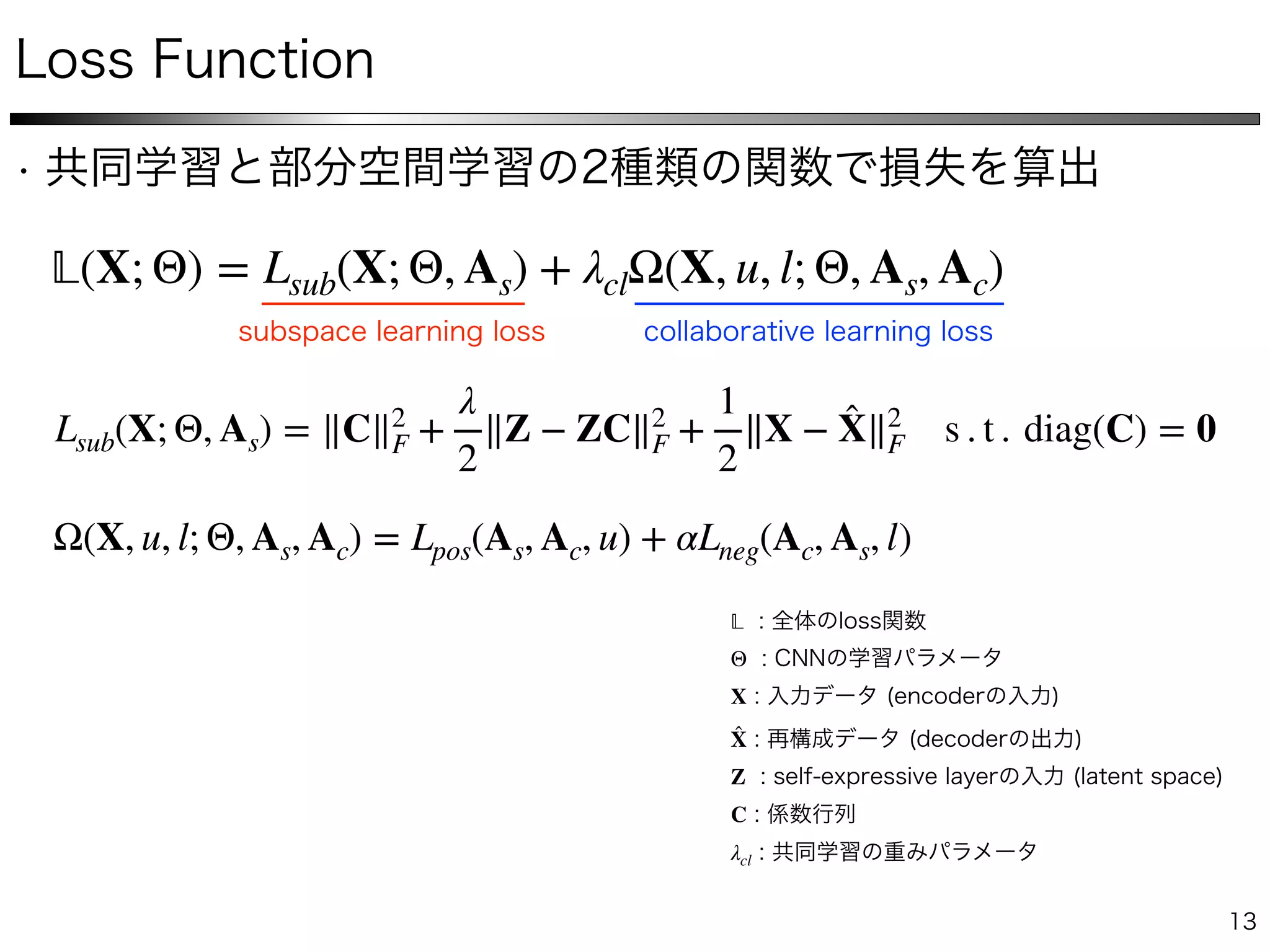

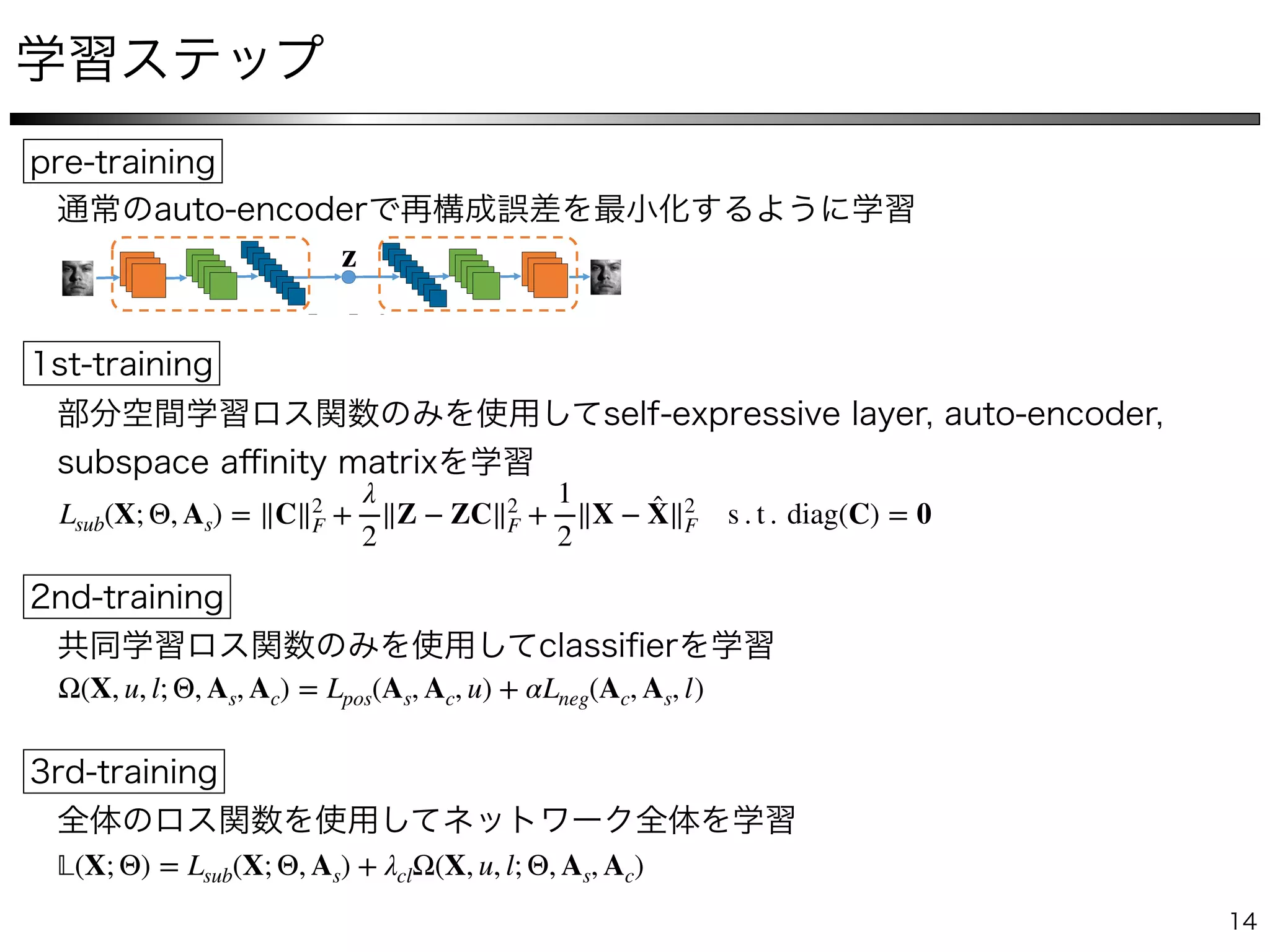

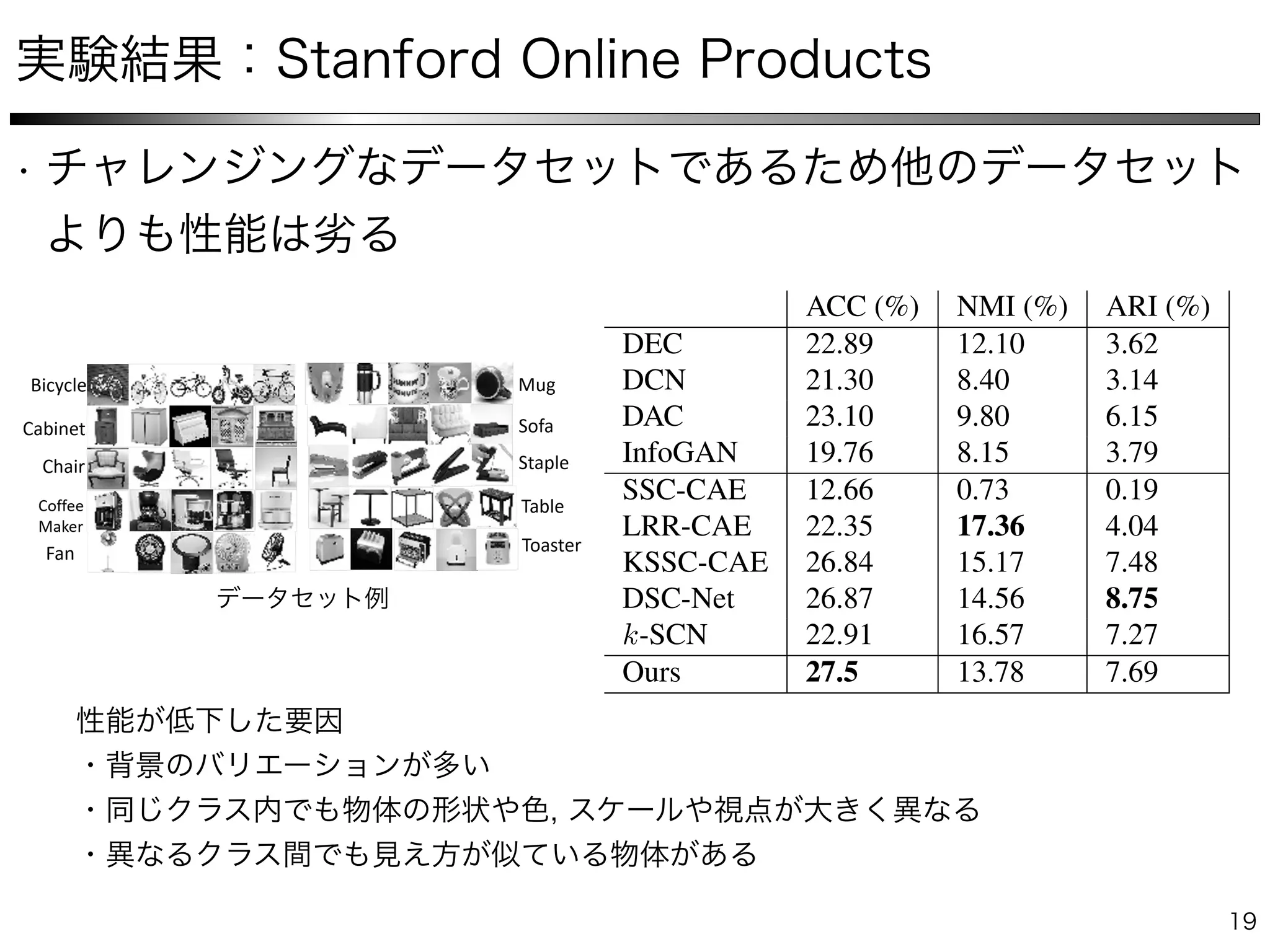

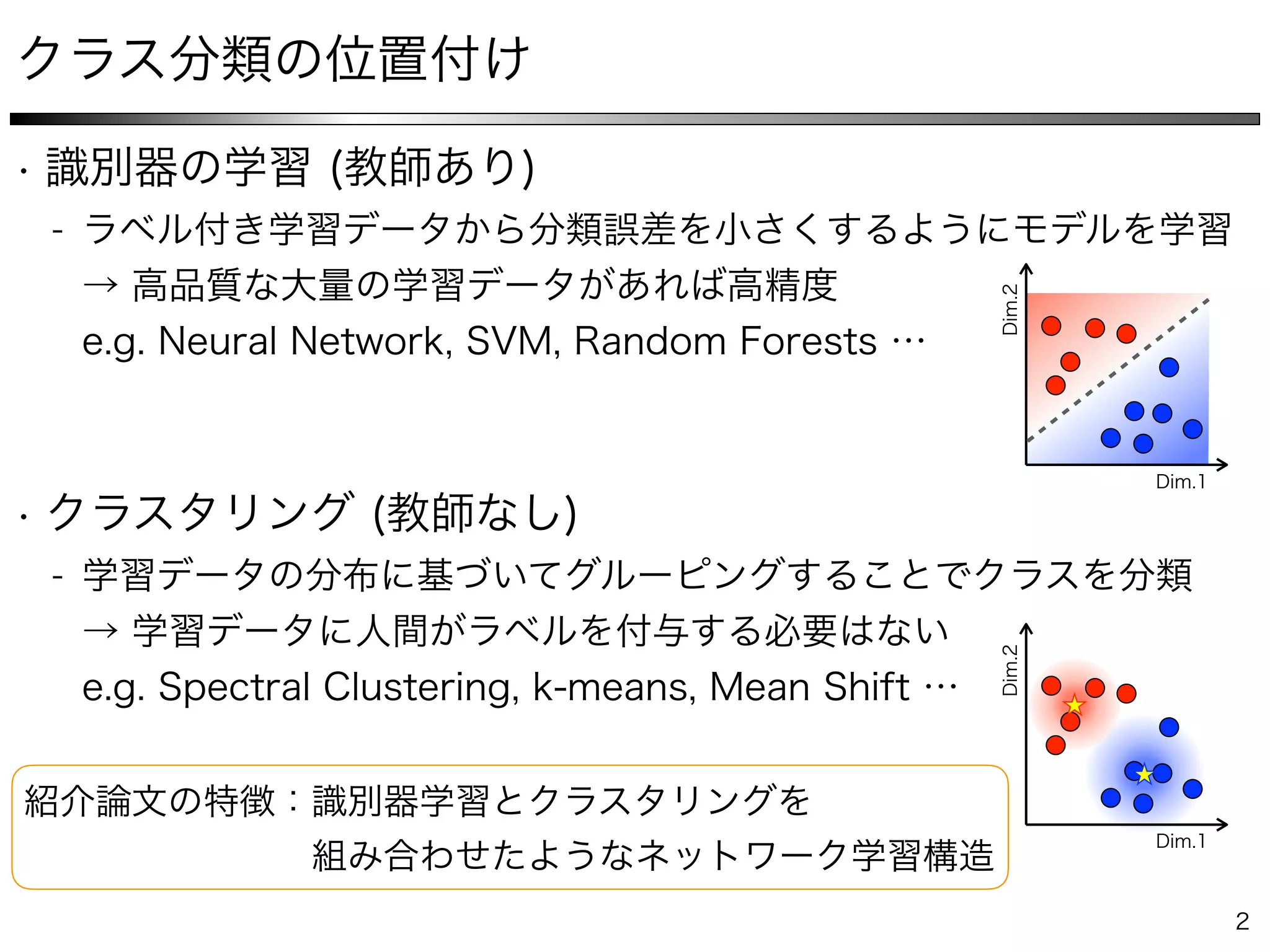

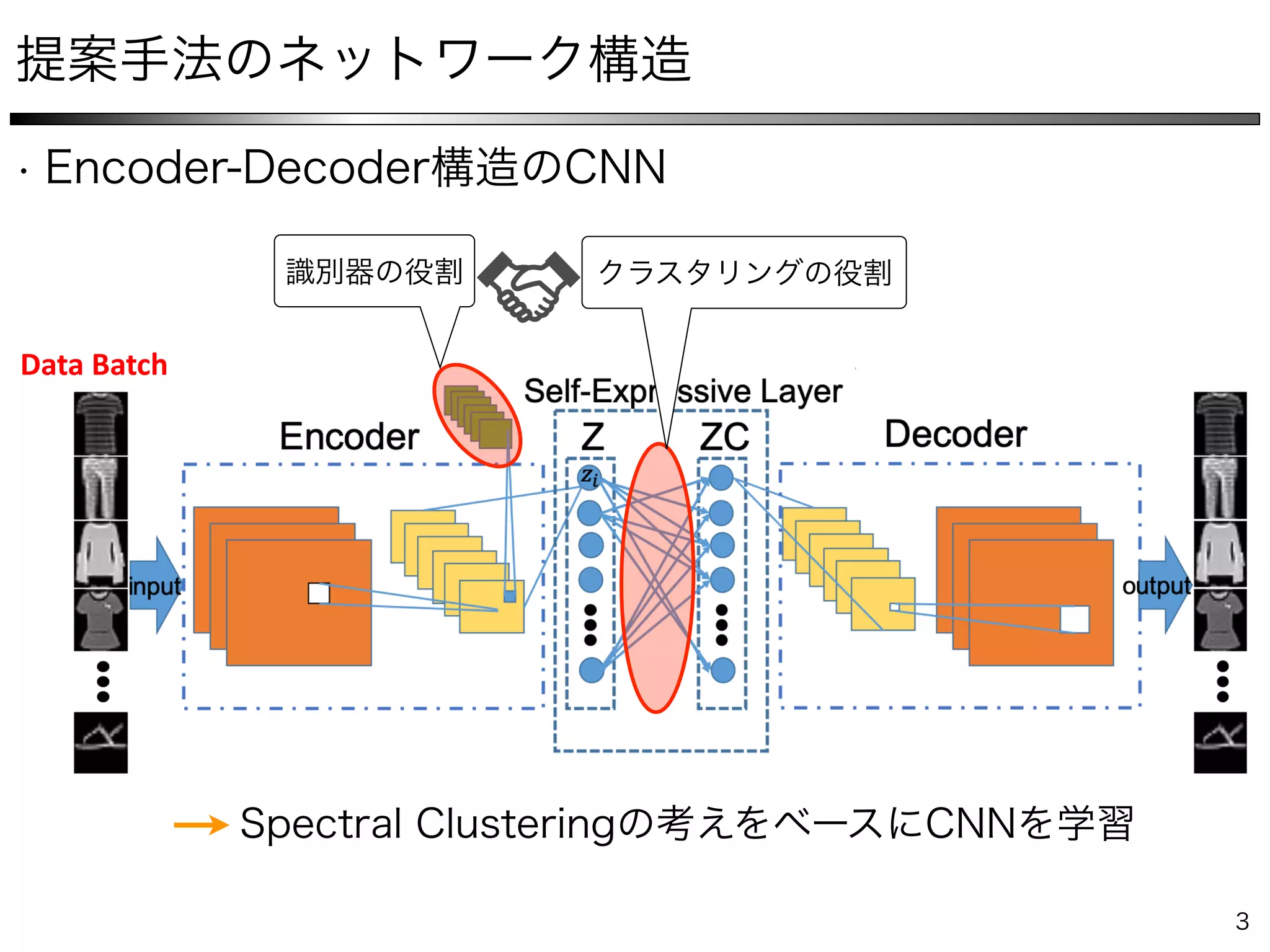

The document describes a method for collaborative subspace clustering using a deep neural network. The network contains an encoder, a self-expressive layer to learn the affinity matrix C, and a decoder. The network is trained end-to-end by minimizing a loss function containing terms for subspace clustering and collaborative learning between the affinity matrix C and a classifier's output affinity matrix. The loss encourages C to be more confident in identifying points from the same class compared to the classifier.

![min

C

∥C∥p s . t . X = XC, diag(C) = 0 X ∈ ℝD×N

X = [x1, x2, ⋯, xN]

xi D

C ∈ ℝN×N 4

S1

S2

S3

yi

0 5 10 15 20 25 30

−0.05

0

0.05

0.1

q = ∞

0 5 10 15 20 25 30

−0.1

−0.05

0

0.05

0.1

0.15

q = 2

0 5 10 15 20 25 30

−0.2

0

0.2

0.4

q = 1

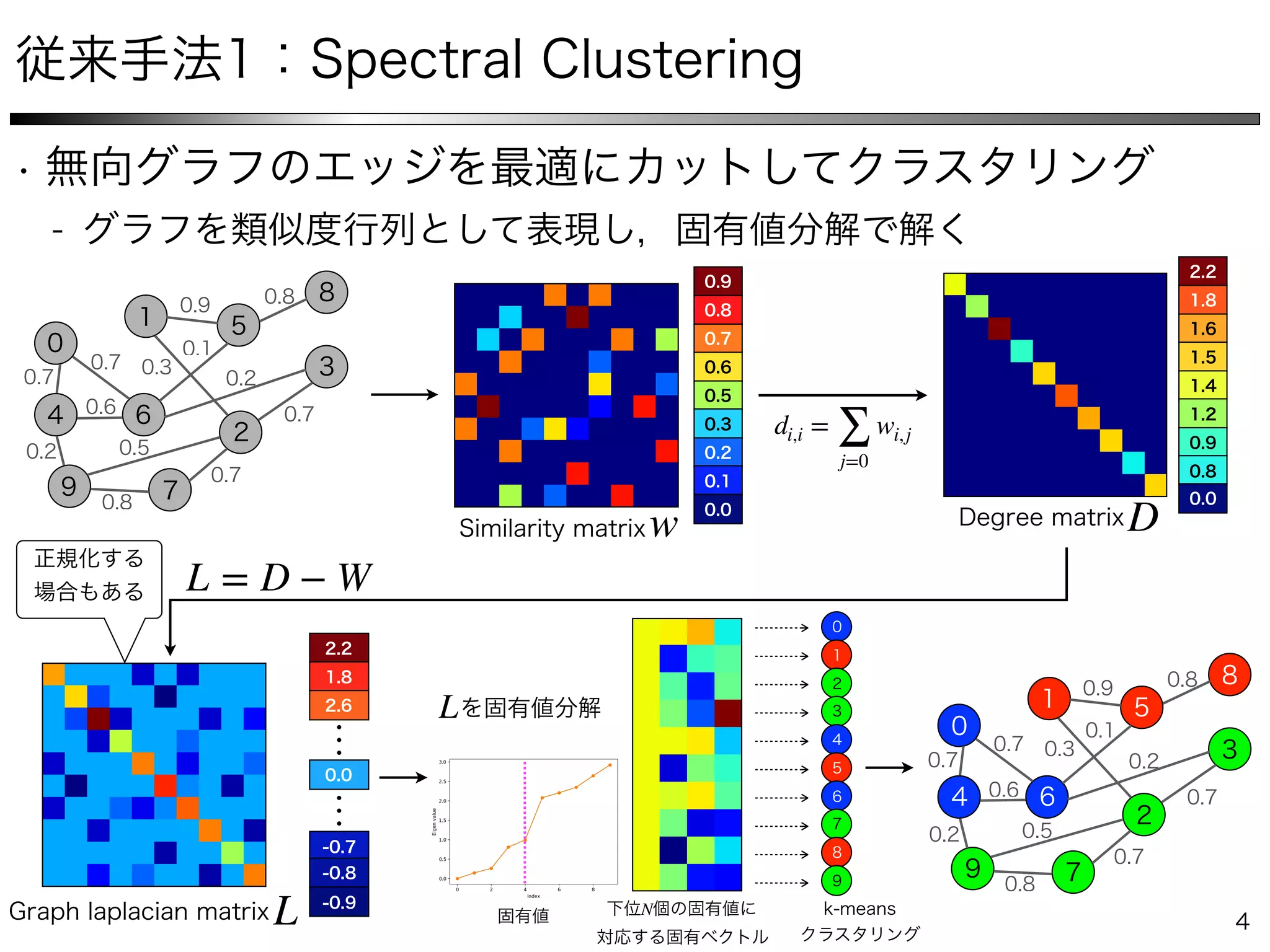

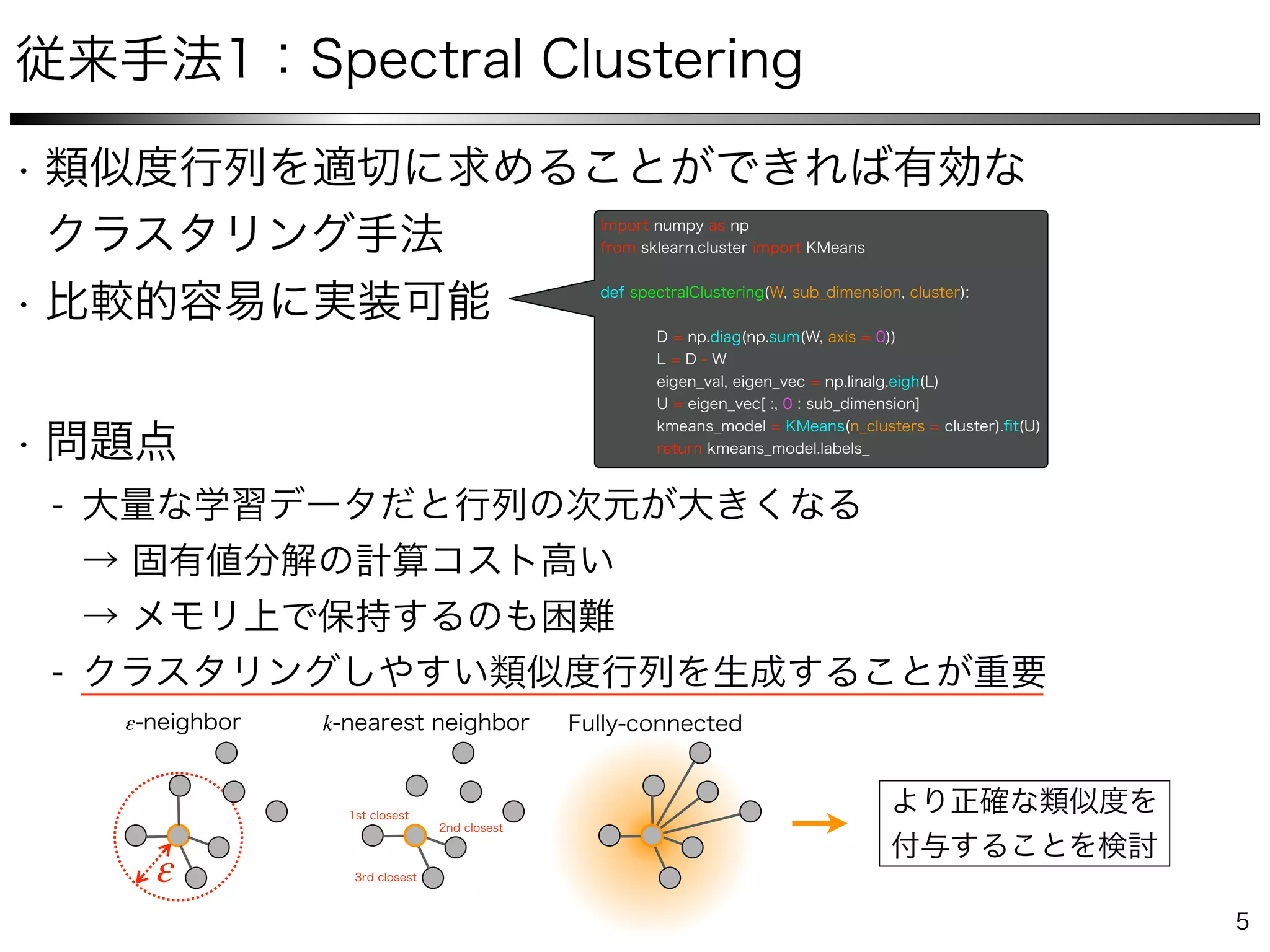

Fig. 3. Three subspaces in R3

with 10 data points in each subspace, ordered such that the fist and the last 10 points belong to S1 and

S3, respectively. The solution of the `q-minimization program in (3) for yi lying in S1 for q = 1, 2, 1 is shown. Note that as the value of q

decreases, the sparsity of the solution increases. For q = 1, the solution corresponds to choosing two other points lying in S1.

Different choices of q have different effects in the obtained

solution. Typically, by decreasing the value of q from infinity

toward zero, the sparsity of the solution increases, as shown in

Figure 3. The extreme case of q = 0 corresponds to the general

NP-hard problem [51] of finding the sparsest representation of

the given point, as the `0-norm counts the number of nonzero

elements of the solution. Since we are interested in efficiently

whose nonzero elements correspond to points from the same

subspace of the given data point. This provides an immediate

choice of the similarity matrix as W = |C| + |C|>

. In other

words, each node i connects itself to a node j by an edge whose

weight is equal to |cij|+|cji|. The reason for the symmetrization

is that, in general, a data point yi 2 S` can write itself as a

linear combination of some points including yj 2 S`. However,

4

S1

S2

S3

yi

0 5 10 15 20 25 30

−0.05

0

0.05

0.1

q = ∞

0 5 10 15 20 25 30

−0.1

−0.05

0

0.05

0.1

0.15

q = 2

0 5 10 15 20 25 30

−0.2

0

0.2

0.4

q = 1

Fig. 3. Three subspaces in R3

with 10 data points in each subspace, ordered such that the fist and the last 10 points belong to S1 and

S3, respectively. The solution of the `q-minimization program in (3) for yi lying in S1 for q = 1, 2, 1 is shown. Note that as the value of q

decreases, the sparsity of the solution increases. For q = 1, the solution corresponds to choosing two other points lying in S1.

Different choices of q have different effects in the obtained

solution. Typically, by decreasing the value of q from infinity

toward zero, the sparsity of the solution increases, as shown in

Figure 3. The extreme case of q = 0 corresponds to the general

NP-hard problem [51] of finding the sparsest representation of

the given point, as the `0-norm counts the number of nonzero

elements of the solution. Since we are interested in efficiently

whose nonzero elements correspond to points from the same

subspace of the given data point. This provides an immediate

choice of the similarity matrix as W = |C| + |C|>

. In other

words, each node i connects itself to a node j by an edge whose

weight is equal to |cij|+|cji|. The reason for the symmetrization

is that, in general, a data point yi 2 S` can write itself as a

linear combination of some points including yj 2 S`. However,

4

S1

S2

S3

yi

0 5 10 15 20 25 30

−0.05

0

0.05

0.1

q = ∞

0 5 10 15 20 25 30

−0.1

−0.05

0

0.05

0.1

0.15

q = 2

0 5 10 15 20 25 30

−0.2

0

0.2

0.4

q = 1

Fig. 3. Three subspaces in R3

with 10 data points in each subspace, ordered such that the fist and the last 10 points belong to S1 and

S3, respectively. The solution of the `q-minimization program in (3) for yi lying in S1 for q = 1, 2, 1 is shown. Note that as the value of q

decreases, the sparsity of the solution increases. For q = 1, the solution corresponds to choosing two other points lying in S1.

Different choices of q have different effects in the obtained

solution. Typically, by decreasing the value of q from infinity

toward zero, the sparsity of the solution increases, as shown in

Figure 3. The extreme case of q = 0 corresponds to the general

NP-hard problem [51] of finding the sparsest representation of

the given point, as the `0-norm counts the number of nonzero

elements of the solution. Since we are interested in efficiently

whose nonzero elements correspond to points from the same

subspace of the given data point. This provides an immediate

choice of the similarity matrix as W = |C| + |C|>

. In other

words, each node i connects itself to a node j by an edge whose

weight is equal to |cij|+|cji|. The reason for the symmetrization

is that, in general, a data point yi 2 S` can write itself as a

linear combination of some points including yj 2 S`. However,

p = ∞ p = 1p = 2

{S1, S2, S3}

4

S1

S2

S3

yi

0 5 10 15 20 25 30

−0.05

0

0.05

0.1

q = ∞

0 5 10 15 20 25 30

−0.1

−0.05

0

0.05

0.1

0.15

q = 2

0 5 10 15 20 25 30

−0.2

0

0.2

0.4

q = 1

Fig. 3. Three subspaces in R3

with 10 data points in each subspace, ordered such that the fist and the last 10 points belong to S1 and

S3, respectively. The solution of the `q-minimization program in (3) for yi lying in S1 for q = 1, 2, 1 is shown. Note that as the value of q

decreases, the sparsity of the solution increases. For q = 1, the solution corresponds to choosing two other points lying in S1.

Different choices of q have different effects in the obtained

solution. Typically, by decreasing the value of q from infinity

toward zero, the sparsity of the solution increases, as shown in

Figure 3. The extreme case of q = 0 corresponds to the general

NP-hard problem [51] of finding the sparsest representation of

the given point, as the `0-norm counts the number of nonzero

whose nonzero elements correspond to points from the same

subspace of the given data point. This provides an immediate

choice of the similarity matrix as W = |C| + |C|>

. In other

words, each node i connects itself to a node j by an edge whose

weight is equal to |cij|+|cji|. The reason for the symmetrization

is that, in general, a data point yi 2 S` can write itself as a

xiS1

S2

S3

W = |C| + |C|⊤ ( wi,j = |ci,j | + |cj,i | ) W ∈ ℝN×N

C = C⊤](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/icml2019neuralcollaborativesubspaceclustering-190804015812/75/Neural-Collaborative-Subspace-Clustering-6-2048.jpg)