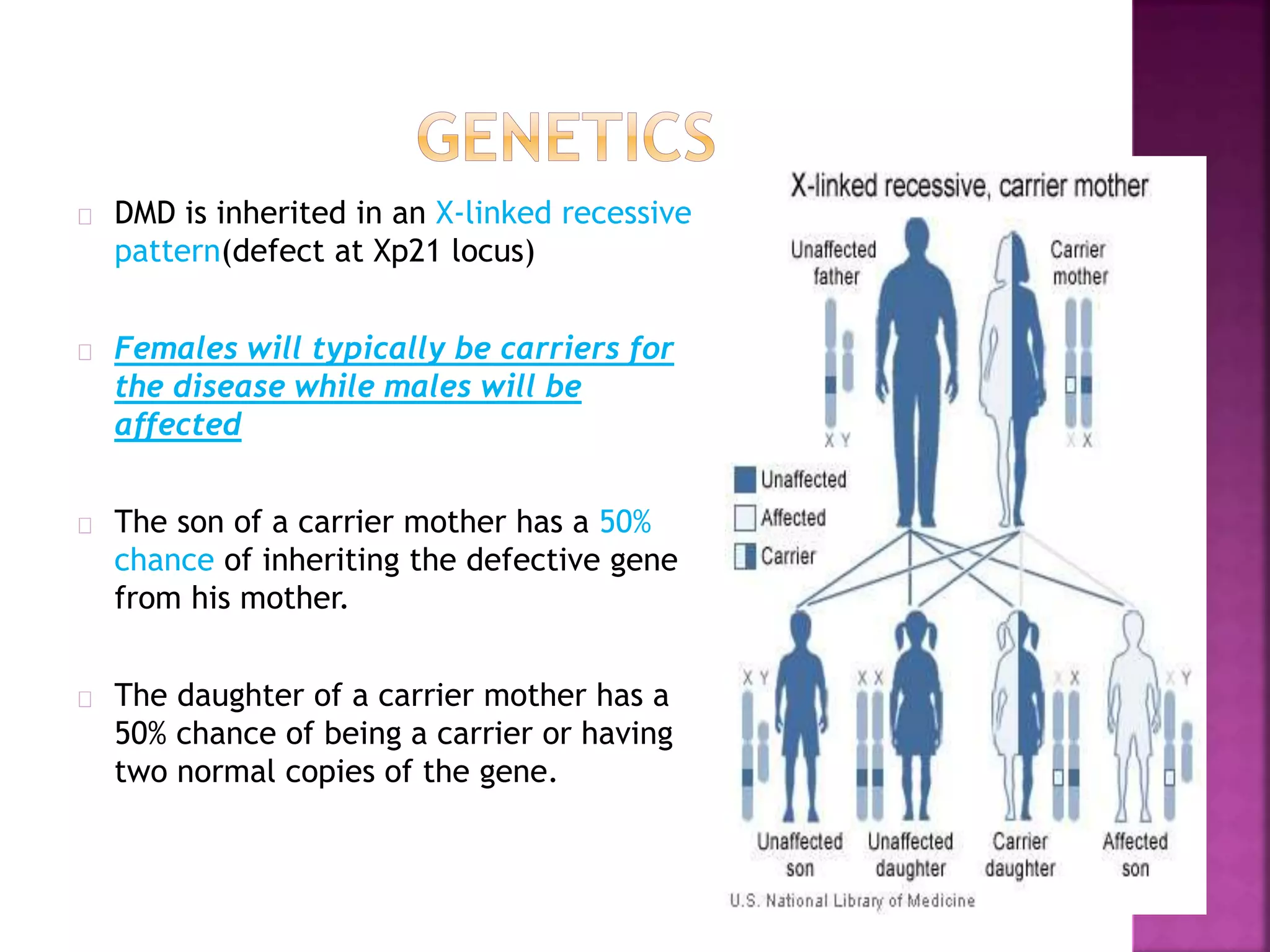

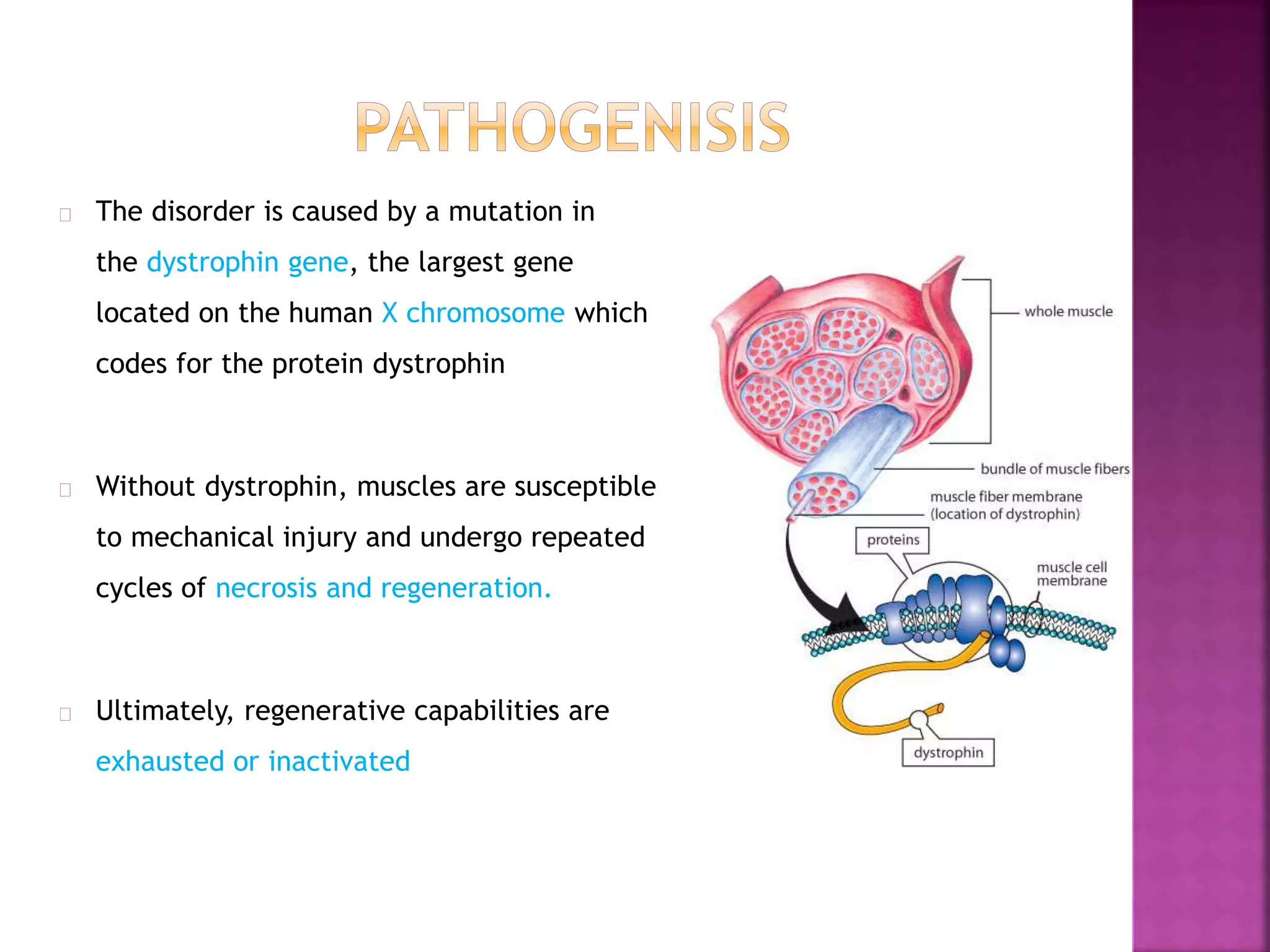

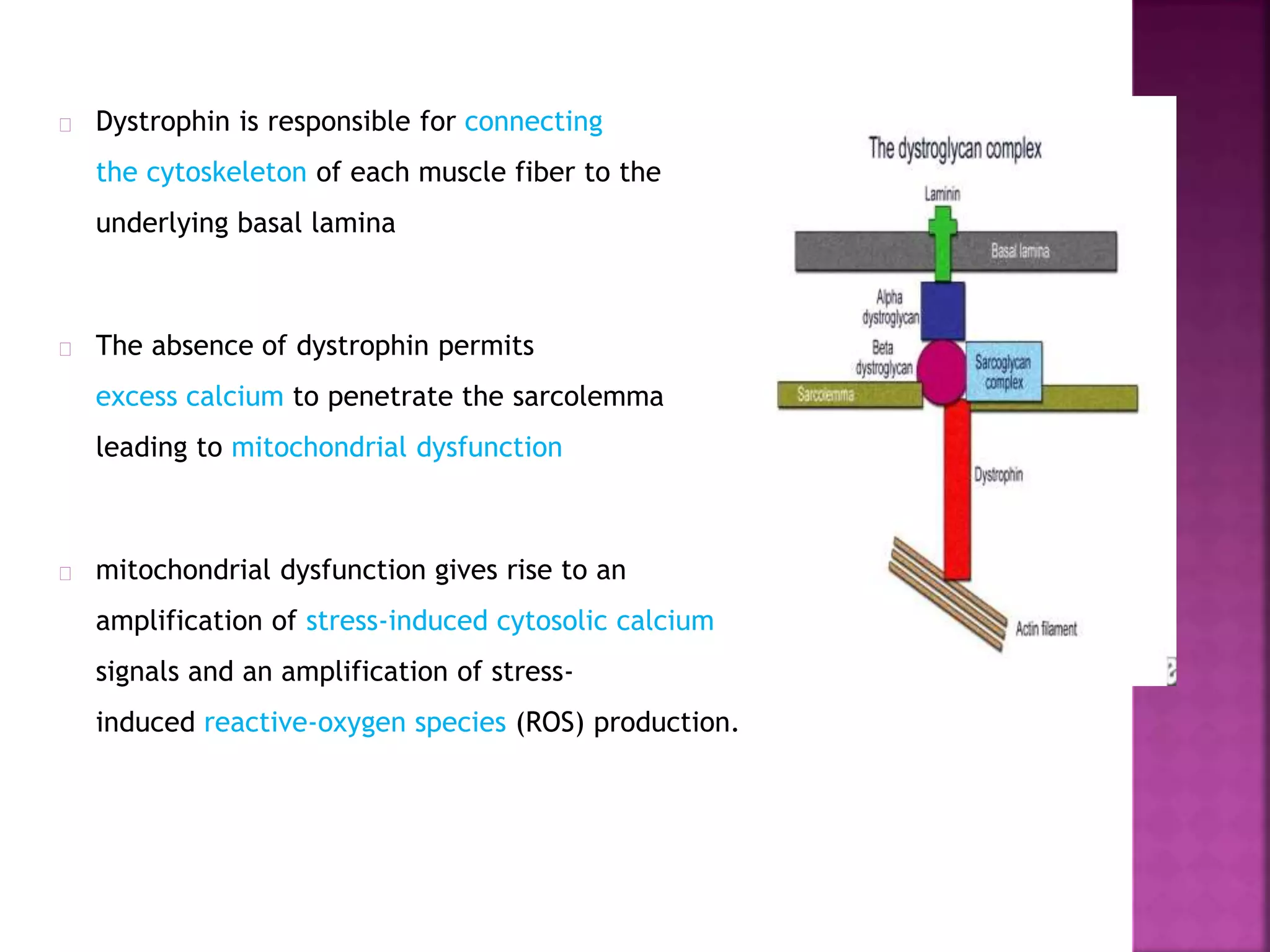

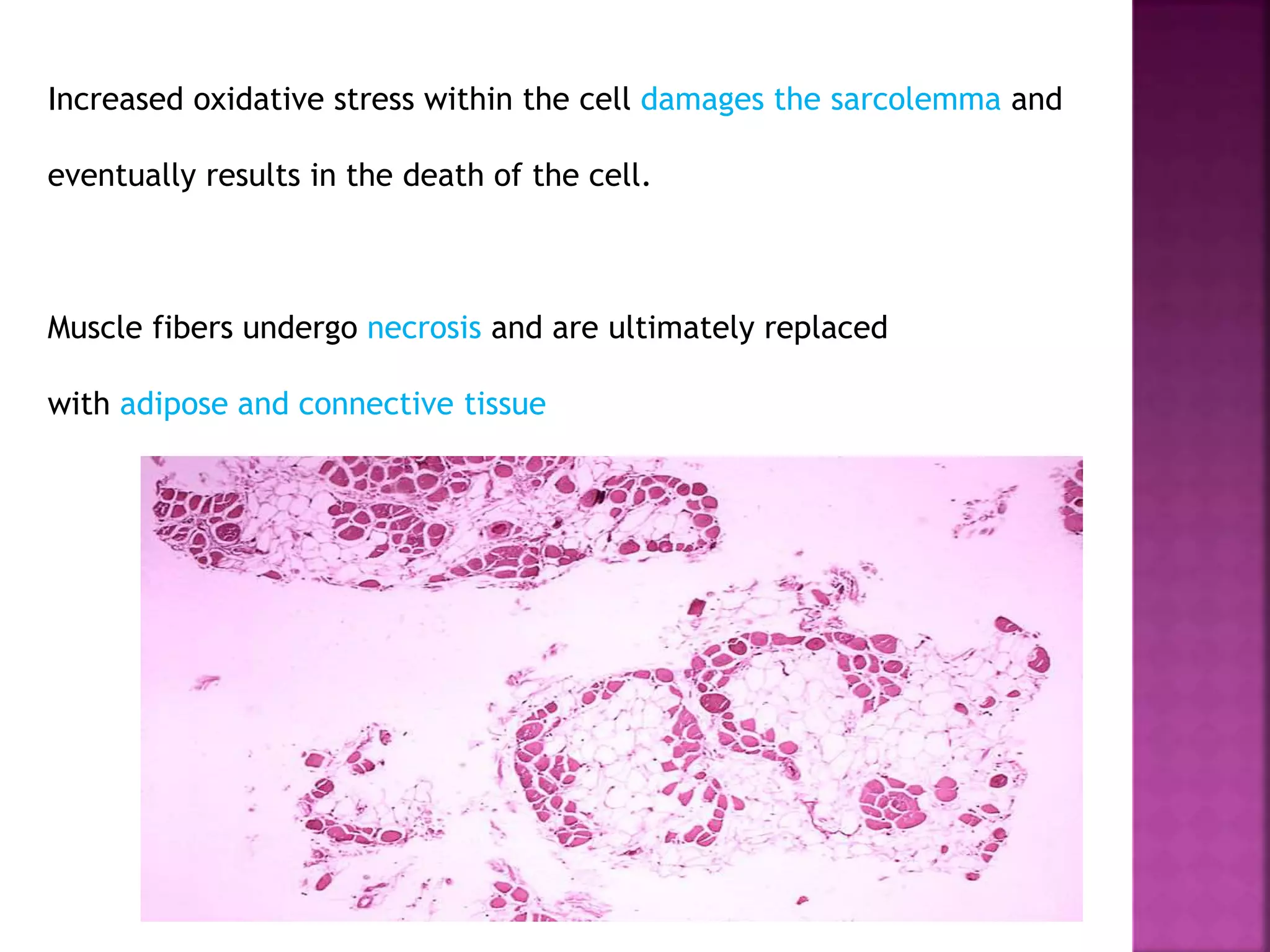

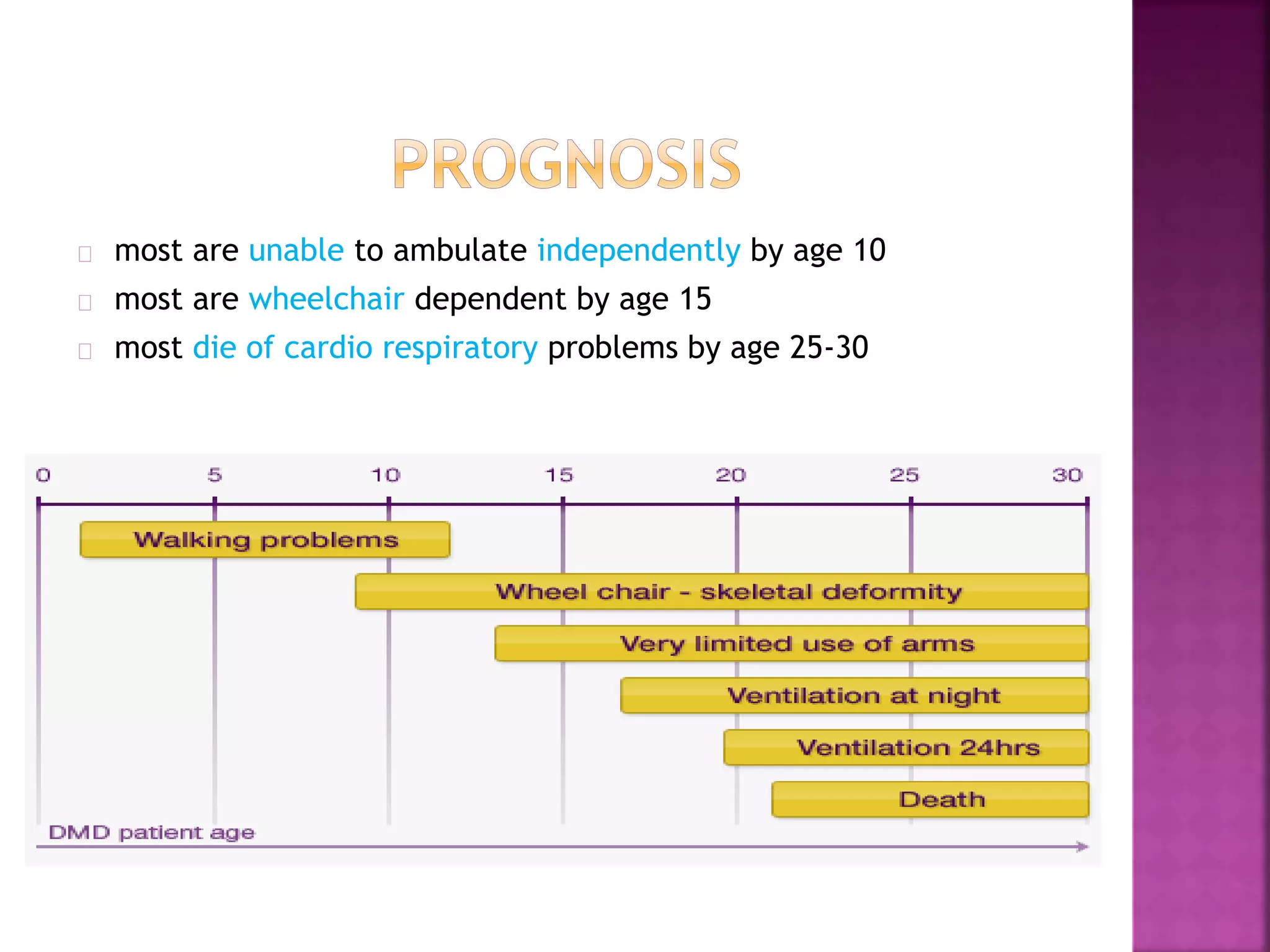

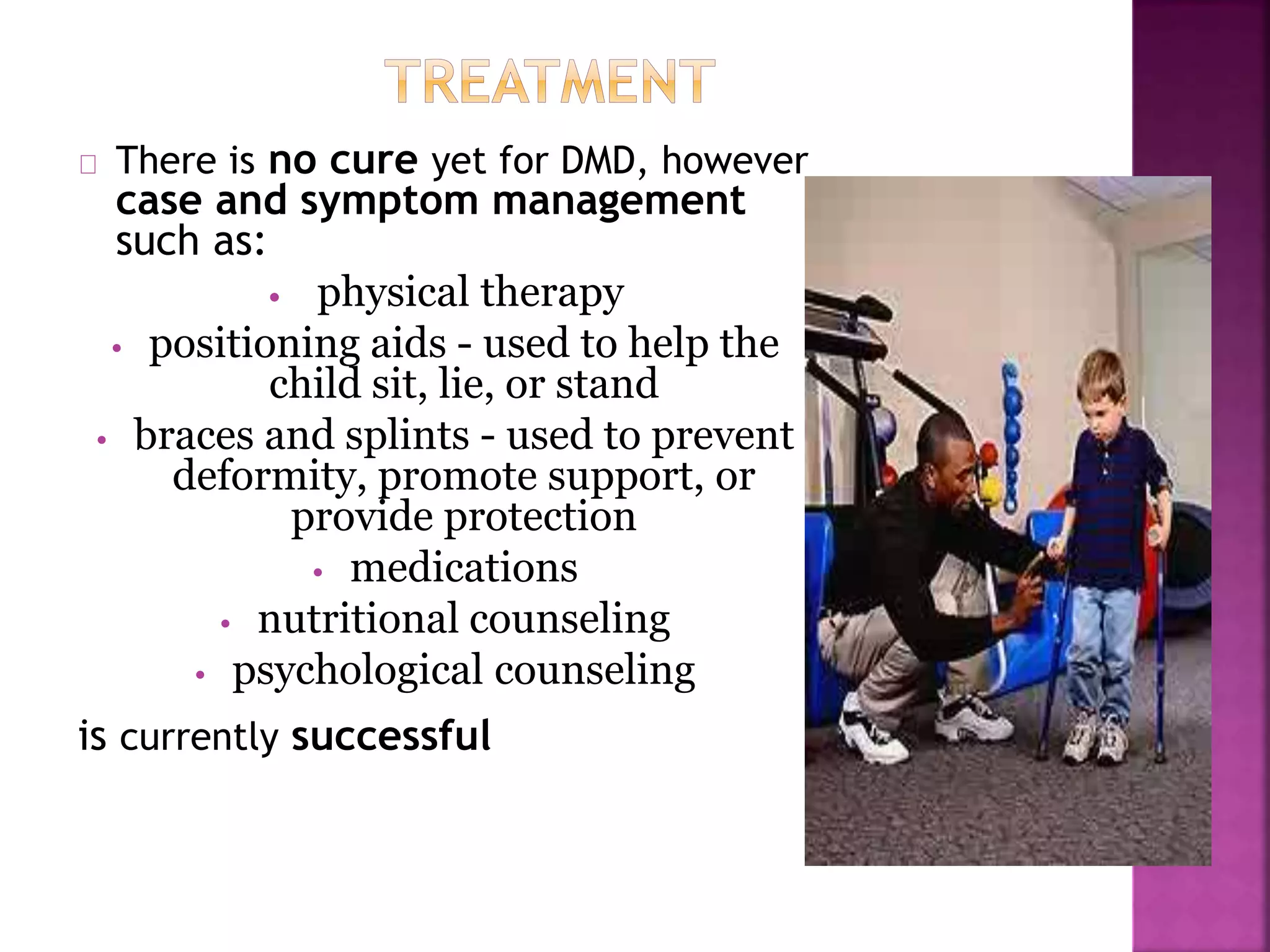

Duchenne muscular dystrophy is a genetic disorder characterized by progressive muscle weakness. It is caused by an absence of the protein dystrophin due to mutations in the dystrophin gene on the X chromosome. The disease mainly affects boys and results in the breakdown of skeletal muscles. While there is no cure, treatment aims to manage symptoms and improve quality of life through physical therapy, bracing, medication, and respiratory/nutritional support. Research continues on new therapies such as gene therapy to replace the missing dystrophin protein.