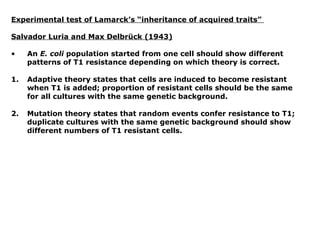

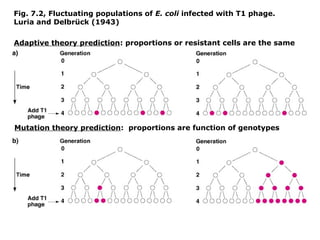

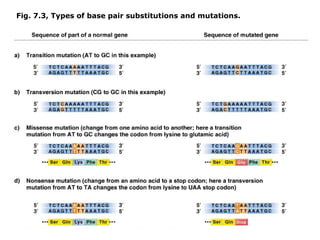

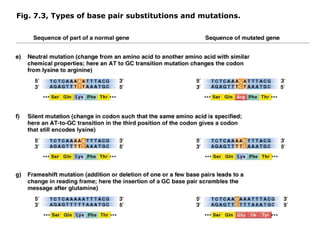

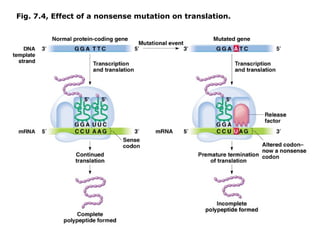

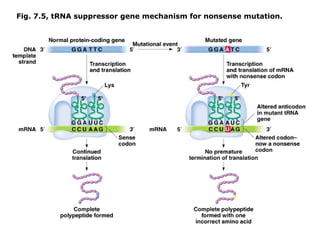

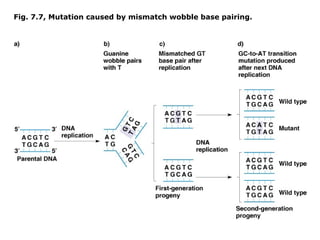

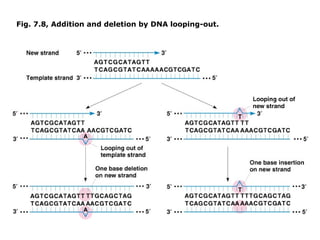

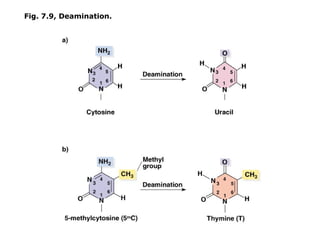

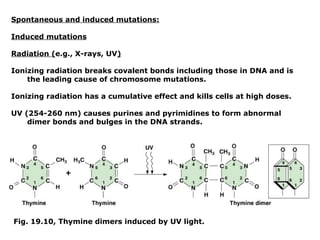

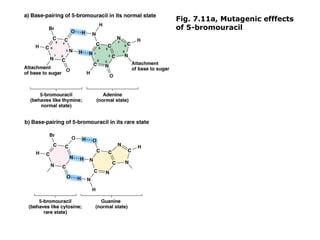

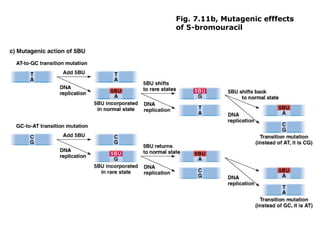

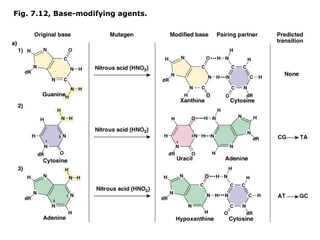

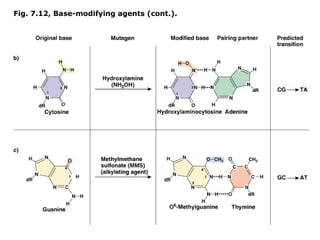

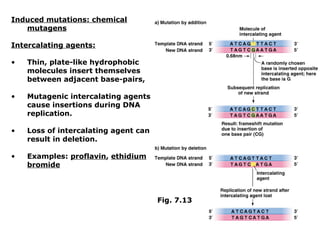

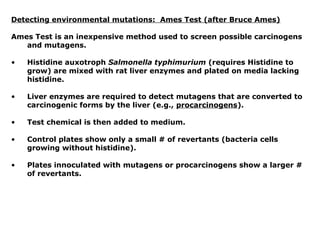

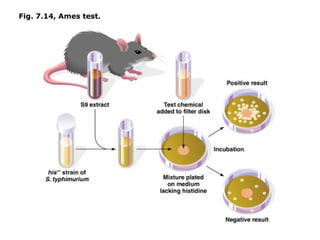

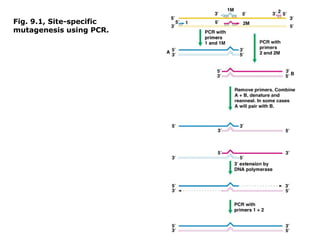

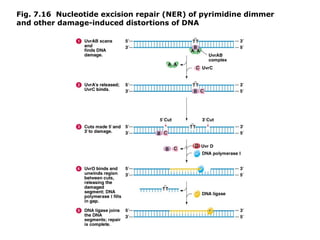

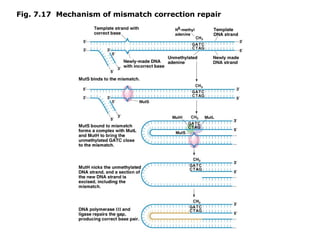

This document summarizes DNA mutation and repair mechanisms. It discusses Lamarck and Darwin's theories of heredity and adaptation. It describes different types of mutations like substitutions, deletions, and frameshifts. Experiments by Luria and Delbrück tested Lamarck and Darwin's theories. The document also discusses DNA repair mechanisms in cells, spontaneous mutations from replication errors, and induced mutations from radiation, chemicals and intercalating agents. The Ames test is described to detect mutagens and carcinogens. Site-specific mutagenesis techniques like PCR can introduce mutations into genes.