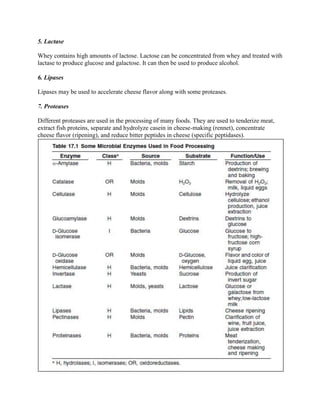

Microbial enzymes are widely used in food processing due to their ability to catalyze specific reactions. About 80% of total enzyme production by dollar value is used by the food industry. Enzymes offer advantages over whole microorganisms by catalyzing single step conversions of specific substrates to products. The main classes of enzymes used in food processing are hydrolases, isomerases, and oxidoreductases. Recombinant DNA technology allows for improved production of enzymes in bacteria and yeast. Immobilizing enzymes allows for their reuse, reducing costs. Thermostable enzymes are advantageous as they maintain activity at higher temperatures, increasing reaction rates. Enzymes are also used to treat food waste by converting components into value-added