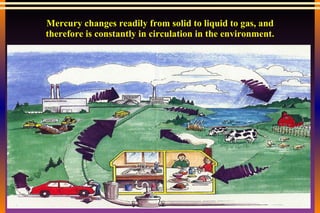

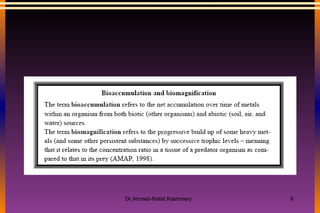

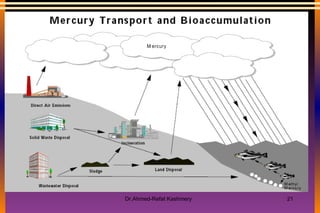

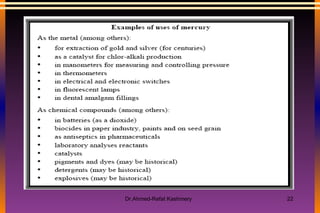

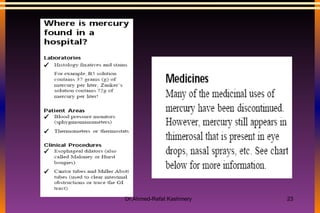

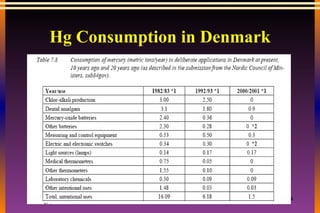

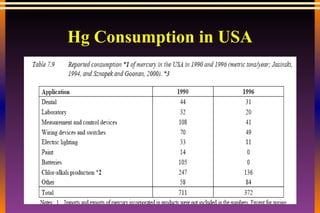

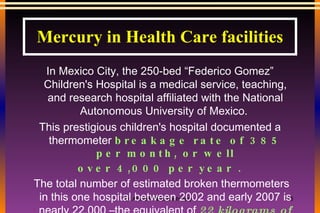

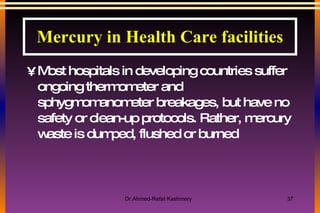

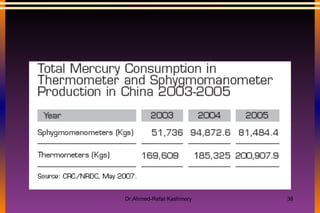

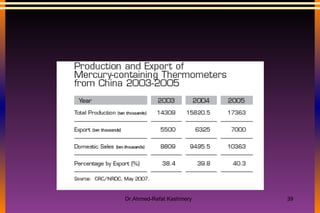

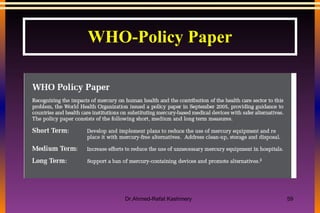

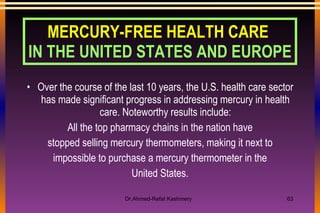

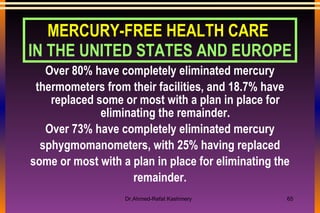

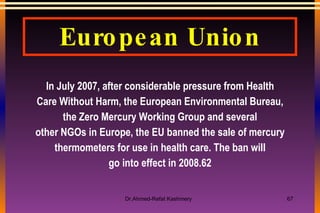

This document summarizes the challenges of mercury use in healthcare facilities in Egypt and discusses alternatives. It outlines the hazards of mercury, especially for healthcare workers and the environment. It discusses obstacles to eliminating mercury, like reluctance to change and lack of affordable alternatives. The document also reviews policies by the WHO and other countries to promote mercury-free healthcare and proper disposal of mercury waste.