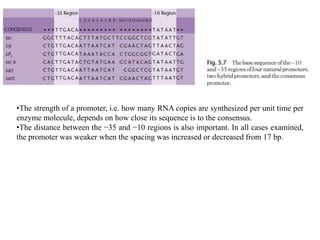

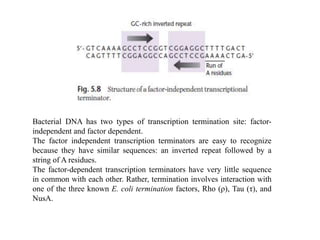

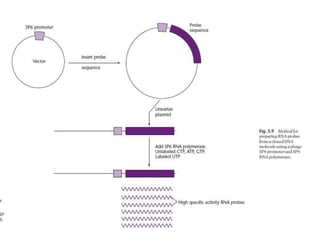

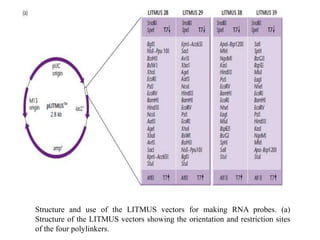

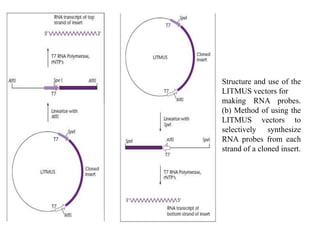

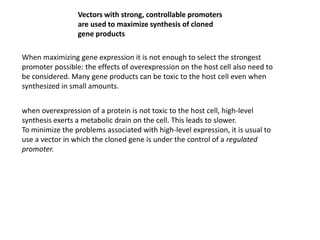

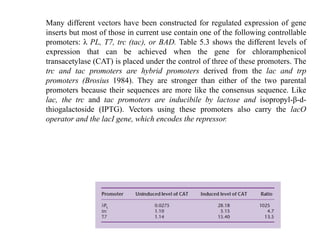

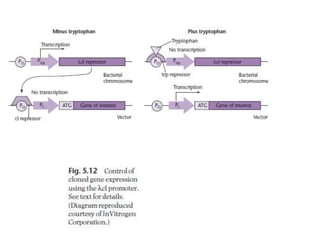

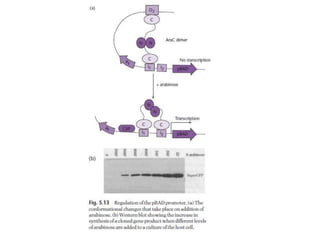

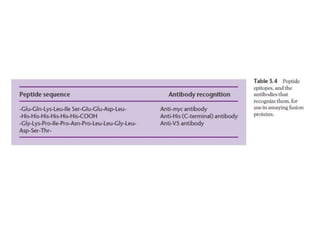

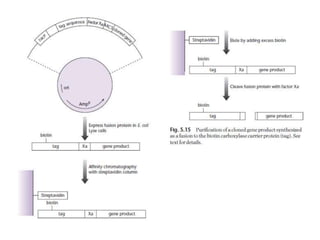

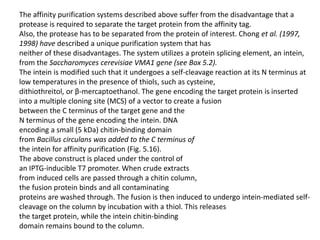

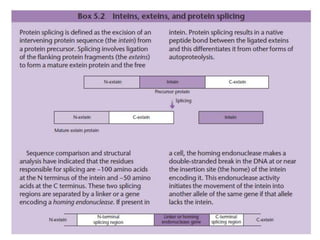

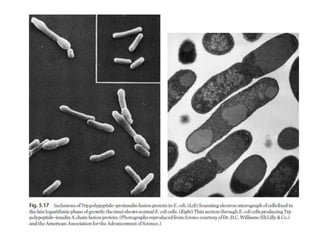

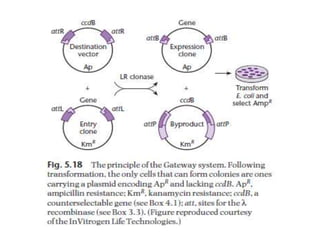

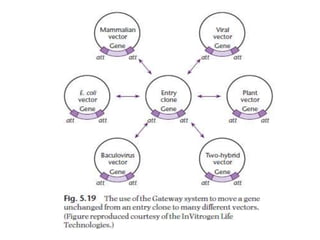

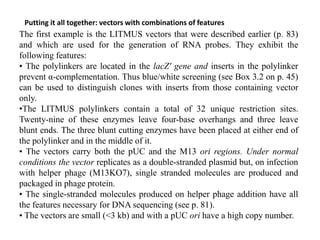

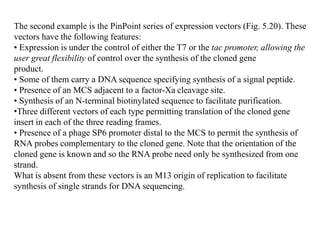

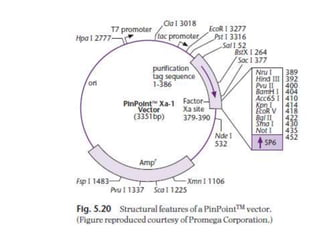

The document discusses several features of vectors used for cloning and expressing genes. It describes how vectors can be engineered to include promoters of different strengths, purification tags, signal sequences, and other elements to optimize expression and purification of cloned gene products. Vectors like LITMUS are designed for making RNA probes while the PinPoint vectors allow expression under different promoters with optional signal peptides or tags to facilitate purification. Together these vectors demonstrate how multiple features can be combined to achieve specific experimental goals.