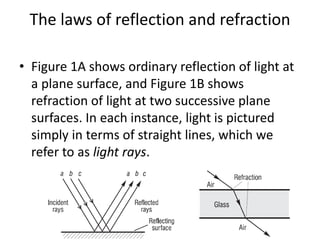

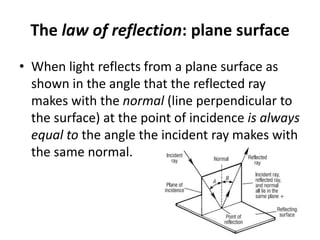

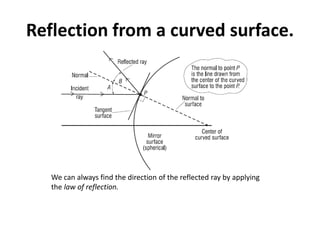

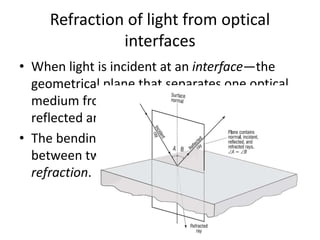

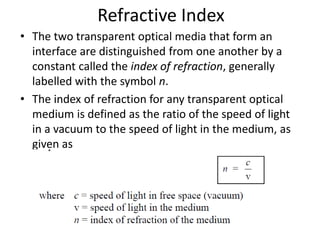

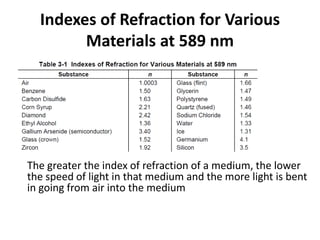

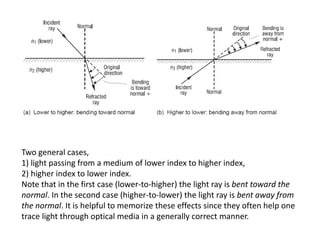

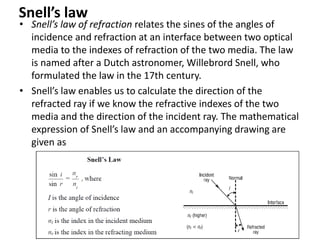

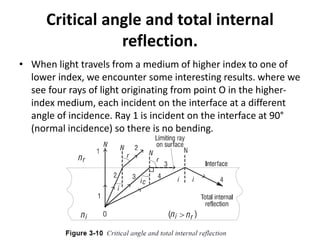

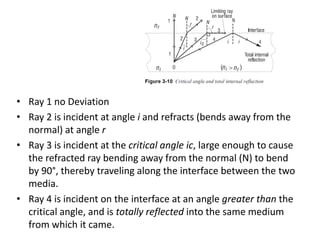

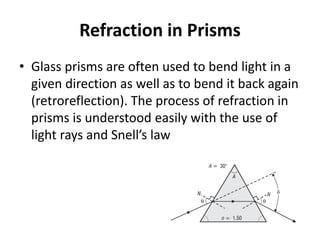

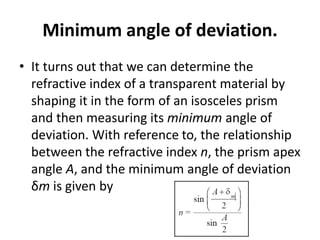

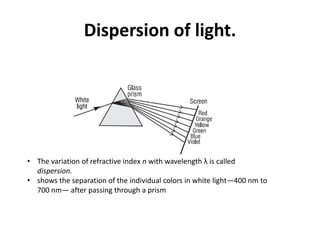

Geometrical optics describes the laws of reflection and refraction of light. When light travels from one medium to another, it can be reflected, refracted, scattered, or absorbed at the interface. Reflection follows the law that the angle of incidence equals the angle of reflection. Refraction is described by Snell's law, which relates the sines of the angles of incidence and refraction to the refractive indices of the media. The bending of light occurs due to changes in speed as it passes between materials of different refractive indices. Prisms are used to demonstrate refraction and dispersion of light into its component wavelengths.