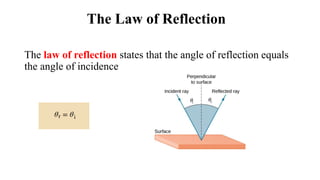

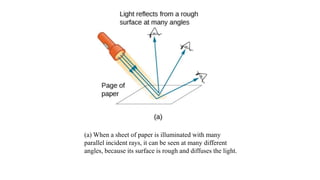

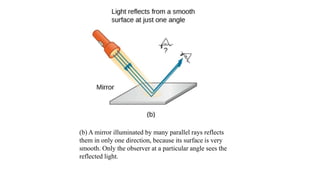

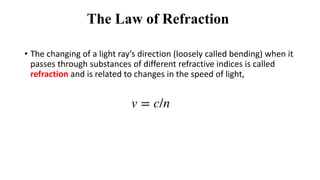

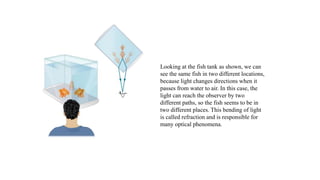

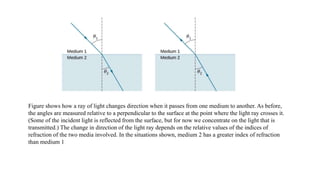

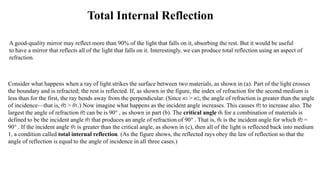

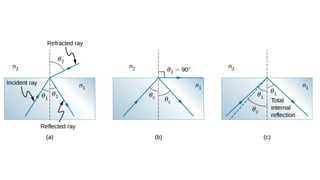

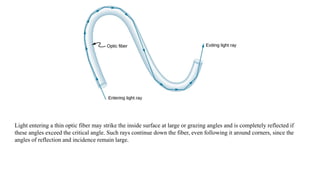

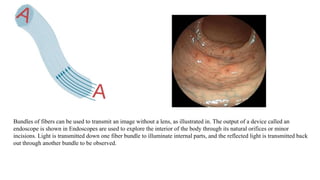

The document summarizes the ray model of light, which describes light traveling in straight lines called rays. It discusses how light rays change direction upon reflection off surfaces or when passing between materials with different refractive indices. This redirection of light rays is governed by two laws: the law of reflection, which states that the angle of reflection equals the angle of incidence, and Snell's law of refraction, which relates the refractive indices of materials to how much a light ray bends when passing between them. Total internal reflection can occur when light passes from a higher to lower refractive index material at an angle greater than the critical angle, causing all the light to be reflected back into the first material.