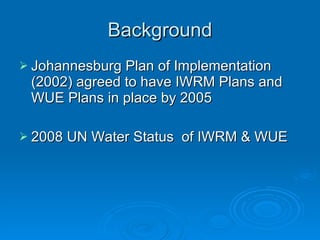

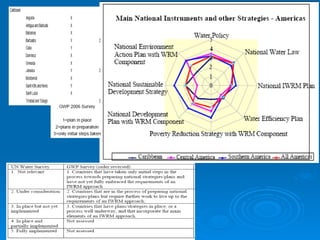

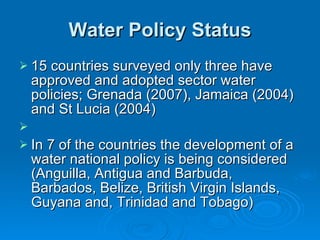

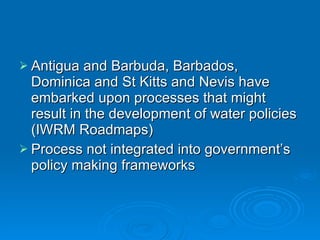

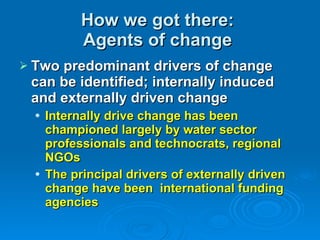

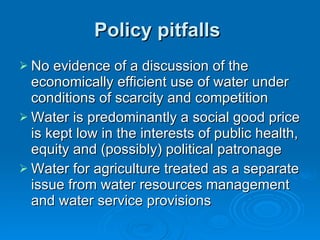

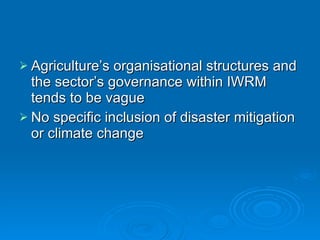

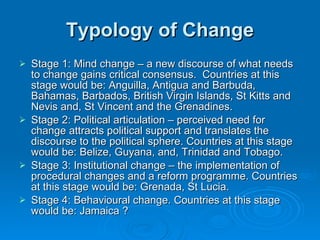

The document discusses the status, experiences, and challenges of Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM) in fifteen Caribbean countries, noting that only three have adopted formal water policies. It highlights the importance of political support, stakeholder participation, and the role of professionals in fostering institutional change, while identifying the need for disaster mitigation and better governance in the sector. The text also outlines stages of change in IWRM implementation across various countries, emphasizing lessons learned regarding the integration of water management and service provision.