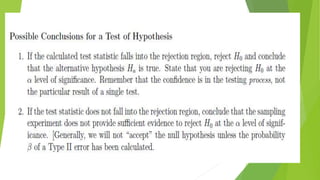

The document discusses hypothesis testing and the scientific research process. It begins by defining a hypothesis as a tentative statement about the relationship between two or more variables that can be tested. It then outlines the typical steps in the scientific research process, which includes forming a question, background research, creating a hypothesis, experiment design, data collection, analysis, conclusions, and communicating results. Finally, it provides details on characteristics of a strong hypothesis, the process of hypothesis testing through statistical analysis, and setting up an experiment for hypothesis testing, including defining hypotheses, significance levels, sample size determination, and calculating standard deviation.

![Tests for statistical significance are used to estimate the probability that a relationship observed in the data

occurred only by chance; the probability that the variables are really unrelated in the population.

To determine whether a result is statistically significant, a researcher calculates a p-value, which is the

probability of observing an effect of the same magnitude or more extreme given that the null hypothesis is

true.

Statistical hypothesis testing is used to determine whether the result of a data set is statistically significant.

This test provides a p-value, representing the probability that random chance could explain the result. In general, a

p-value of 5% or lower is considered to be statistically significant.

The 7 Step Process of Statistical Hypothesis Testing

Step 1: State the Null Hypothesis. ...

Step 2: State the Alternative Hypothesis. ...

Step 3: Set [Math Processing Error] ...

Step 4: Collect Data. ...

Step 5: Calculate a test statistic. ...

Step 6: Construct rejection regions. ...

Step 7: Based on steps 5 and 6, draw a conclusion about H0](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/hypothesistesting-200127093935/85/Hypothesis-testing-34-320.jpg)