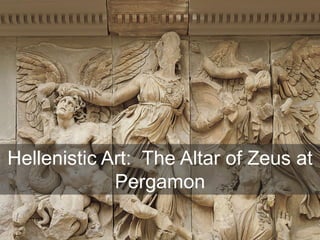

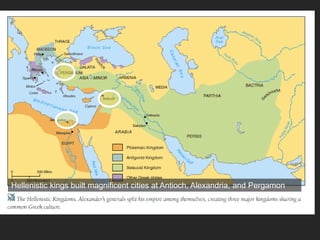

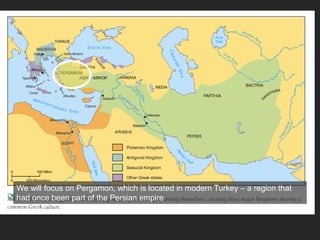

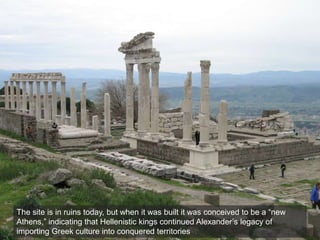

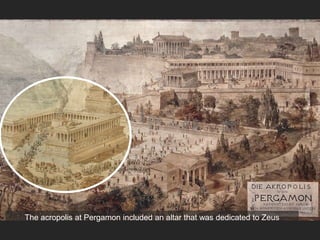

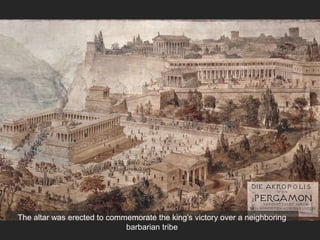

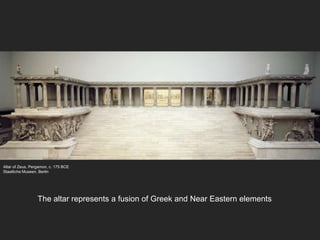

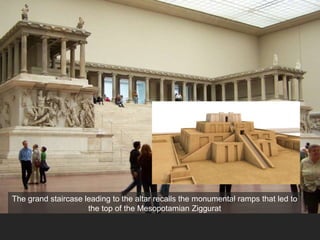

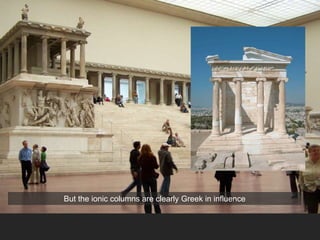

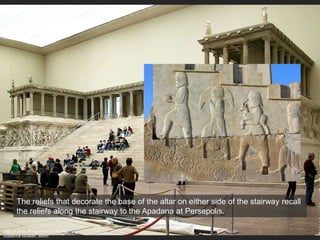

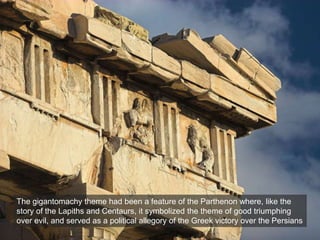

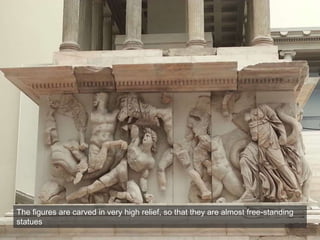

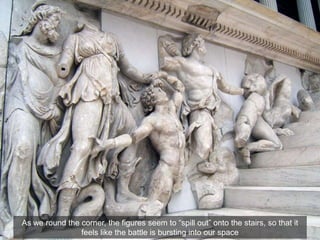

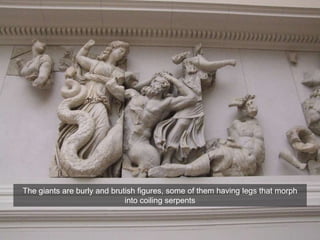

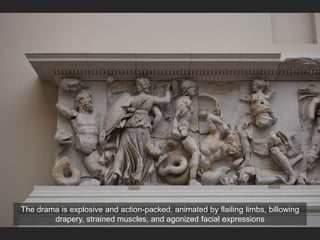

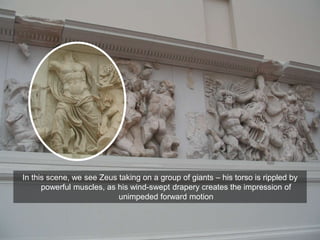

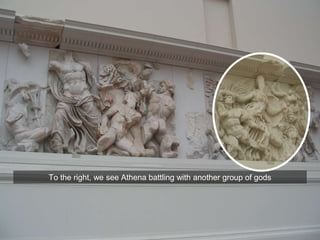

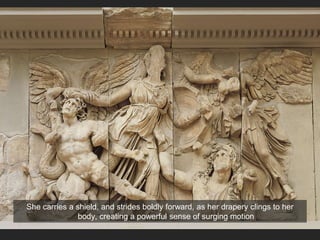

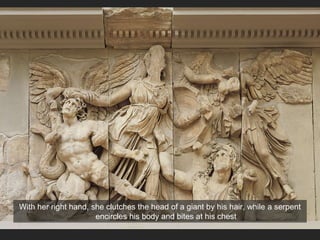

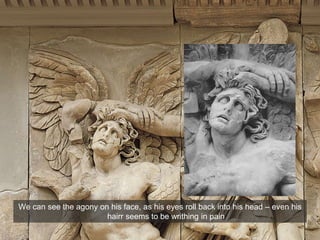

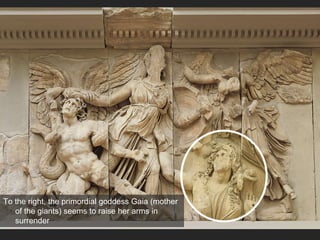

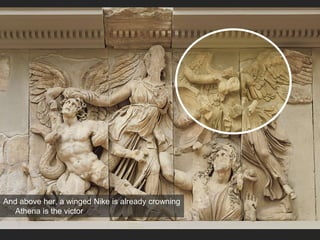

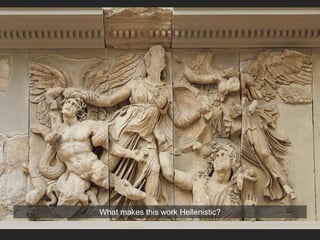

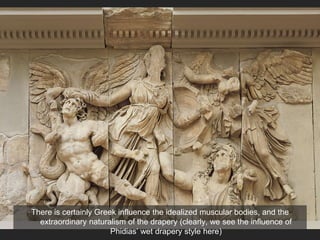

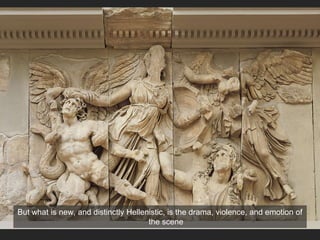

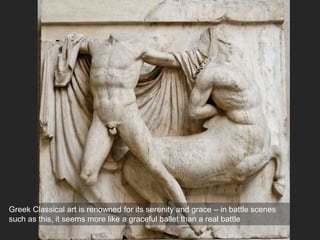

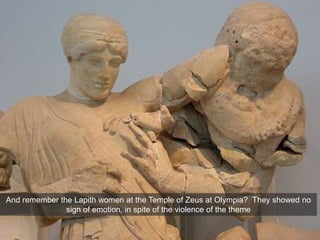

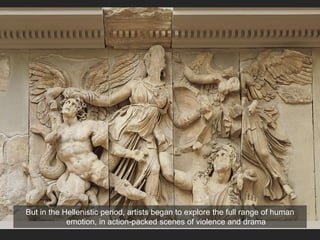

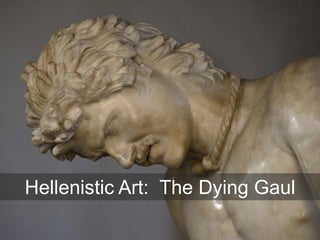

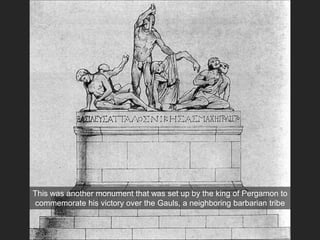

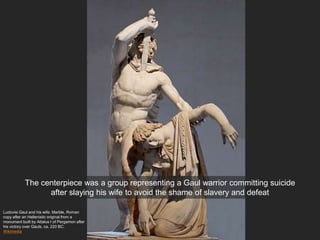

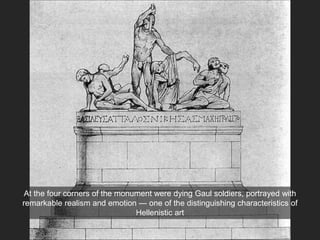

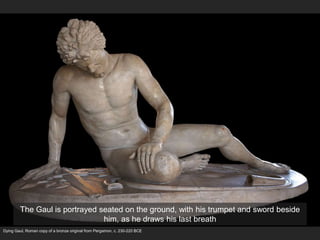

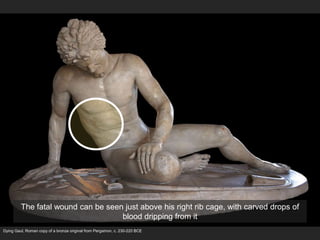

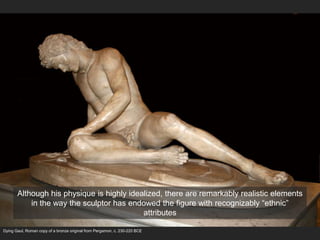

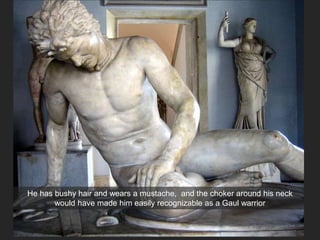

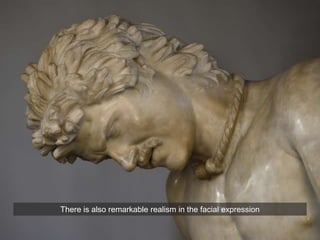

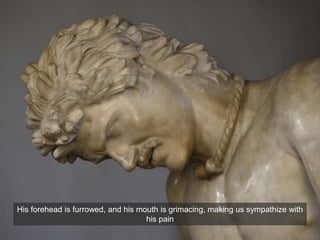

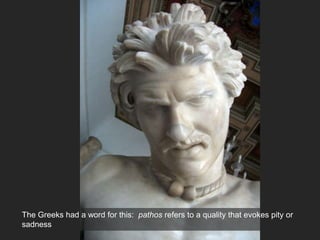

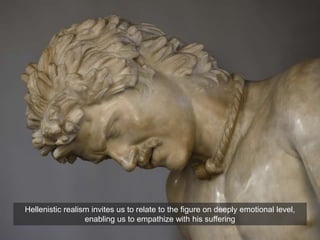

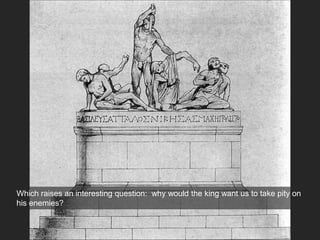

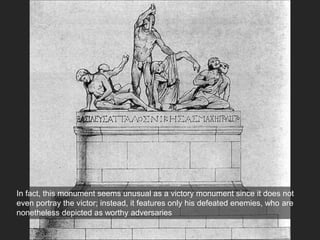

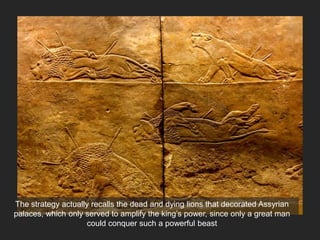

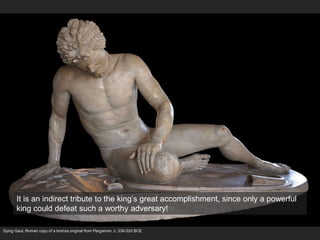

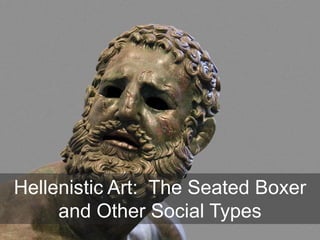

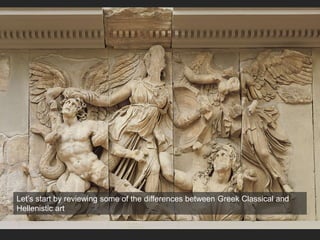

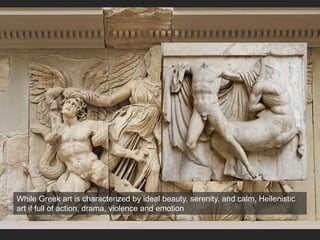

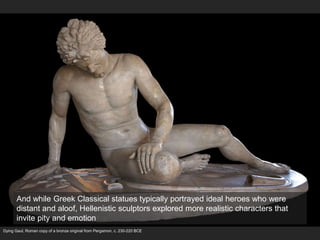

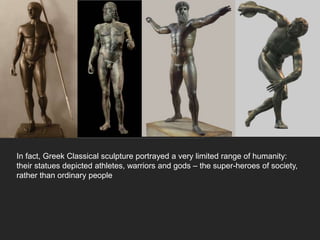

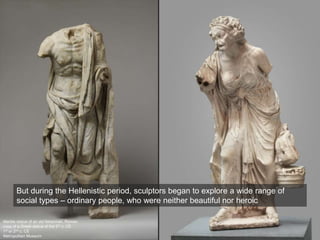

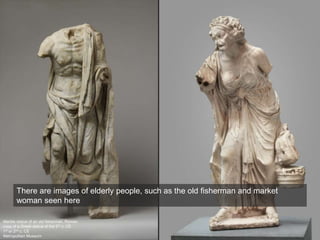

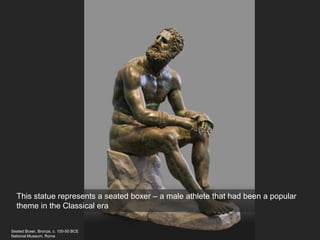

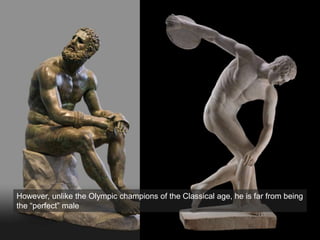

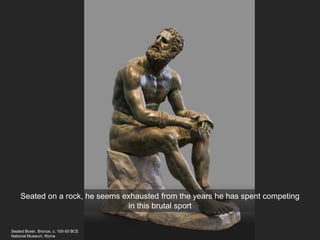

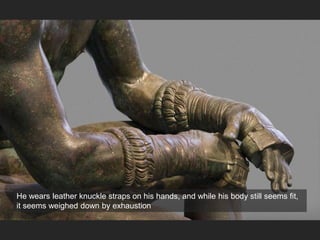

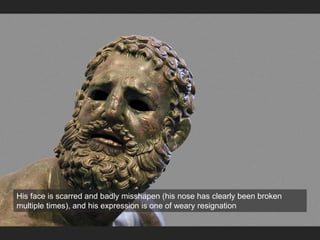

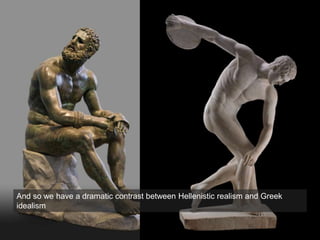

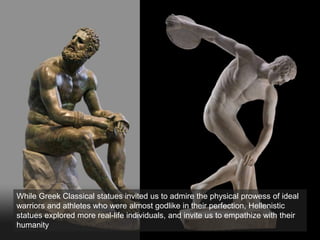

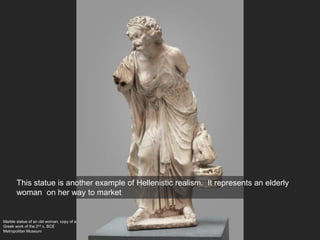

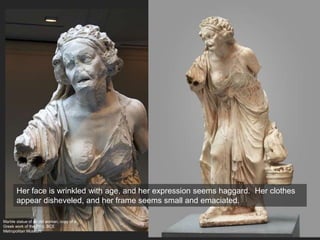

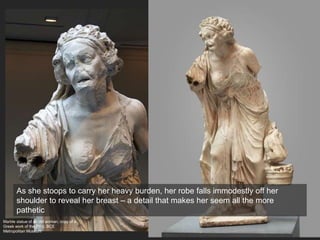

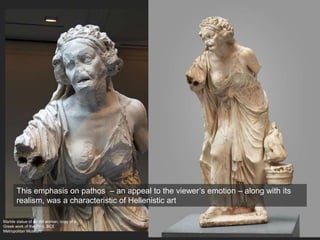

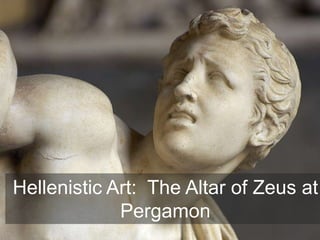

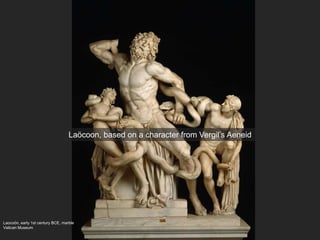

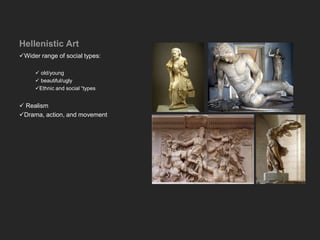

The document discusses Hellenistic artworks from Pergamon including the Altar of Zeus and the Dying Gaul monument. The Altar of Zeus featured a frieze depicting the gods battling giants in high relief, fusing Greek and Near Eastern elements. The Dying Gaul monument commemorated a victory over Gauls by sympathetically portraying a dying enemy warrior, inviting empathy over admiration. Hellenistic art was characterized by dramatic emotion, violence, and realistic portrayals of ordinary people unlike the idealized figures of Classical Greece.