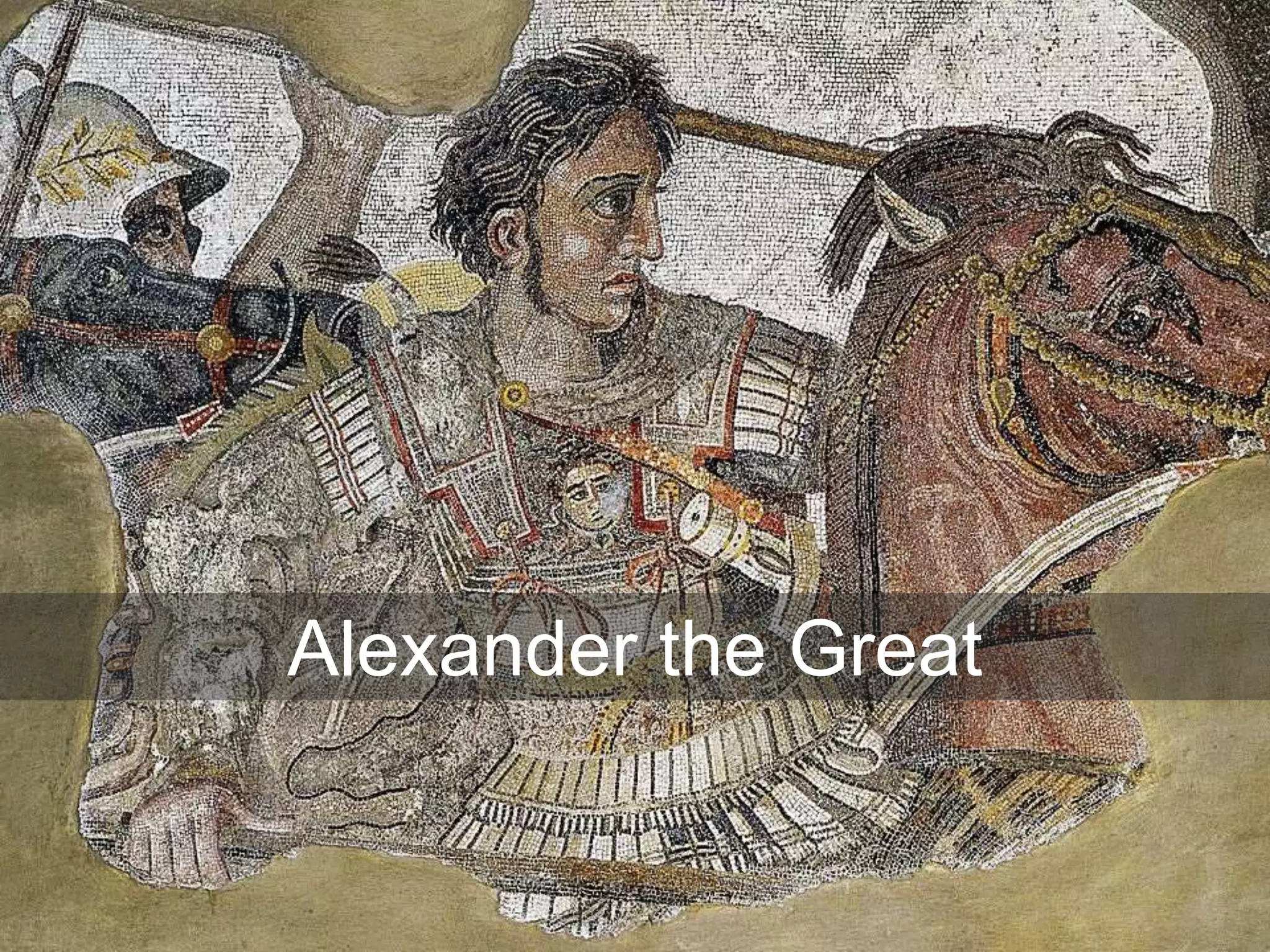

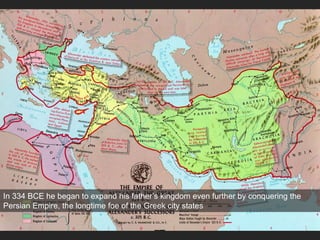

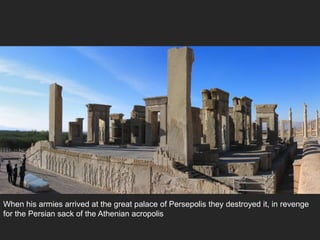

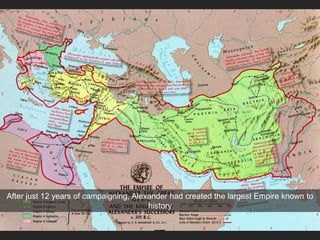

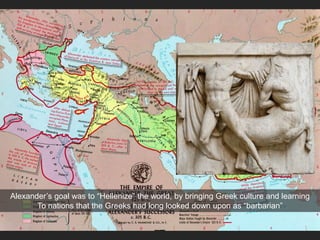

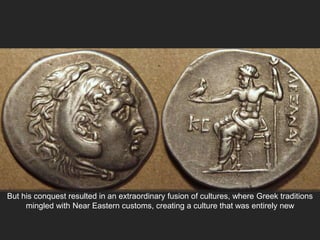

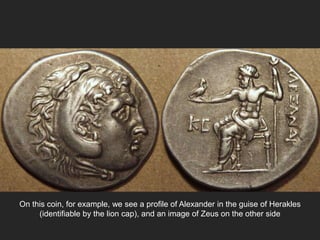

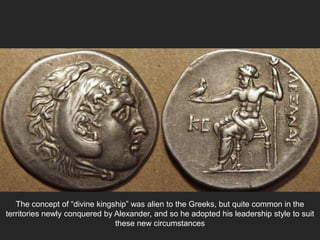

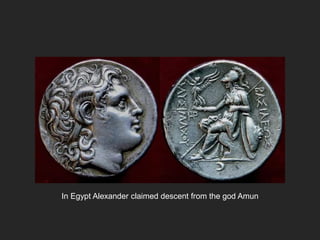

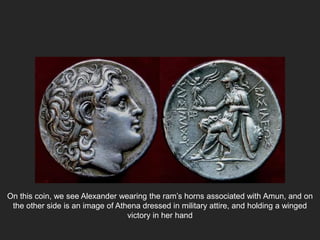

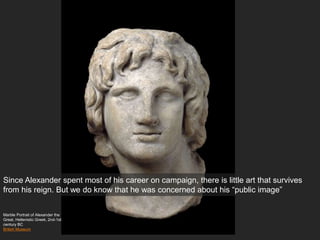

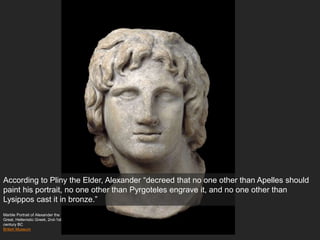

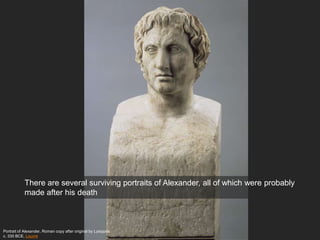

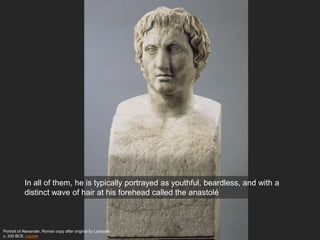

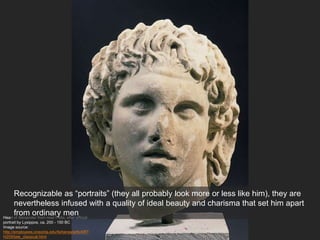

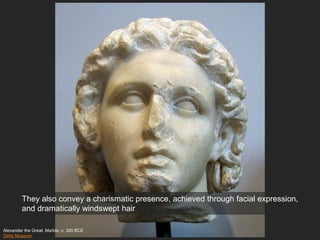

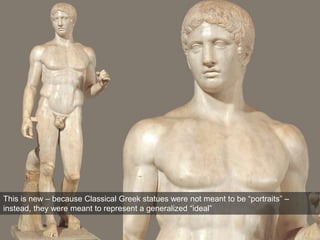

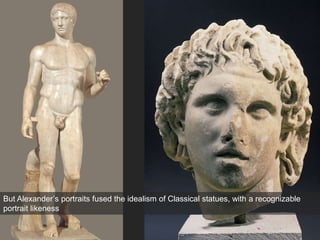

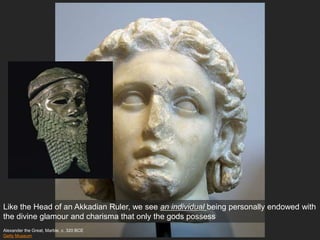

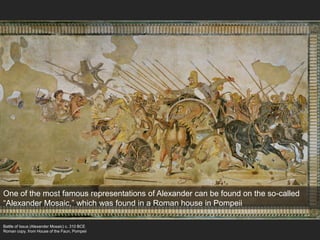

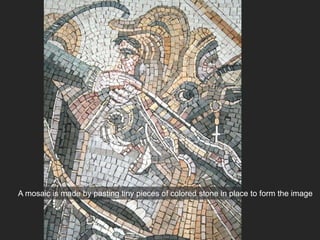

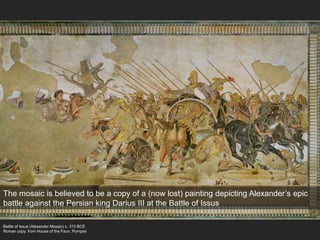

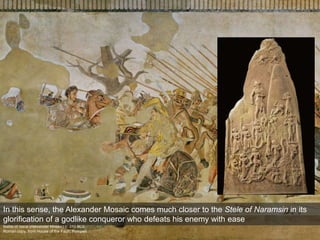

Alexander the Great was the king of Macedonia who conquered much of the known world in the 4th century BCE. He was educated by Aristotle and sought to spread Greek culture throughout his vast empire. Beginning with an invasion of the Persian Empire in 334 BCE, Alexander conquered territories as far as India within just 12 years. His empire was the largest the world had seen up to that point and resulted in the blending of Greek and Near Eastern cultures. Alexander portrayed himself as both a Greek hero and a divine king, as seen in his official portraits depicting him as both idealized and with god-like qualities befitting his unprecedented military successes.