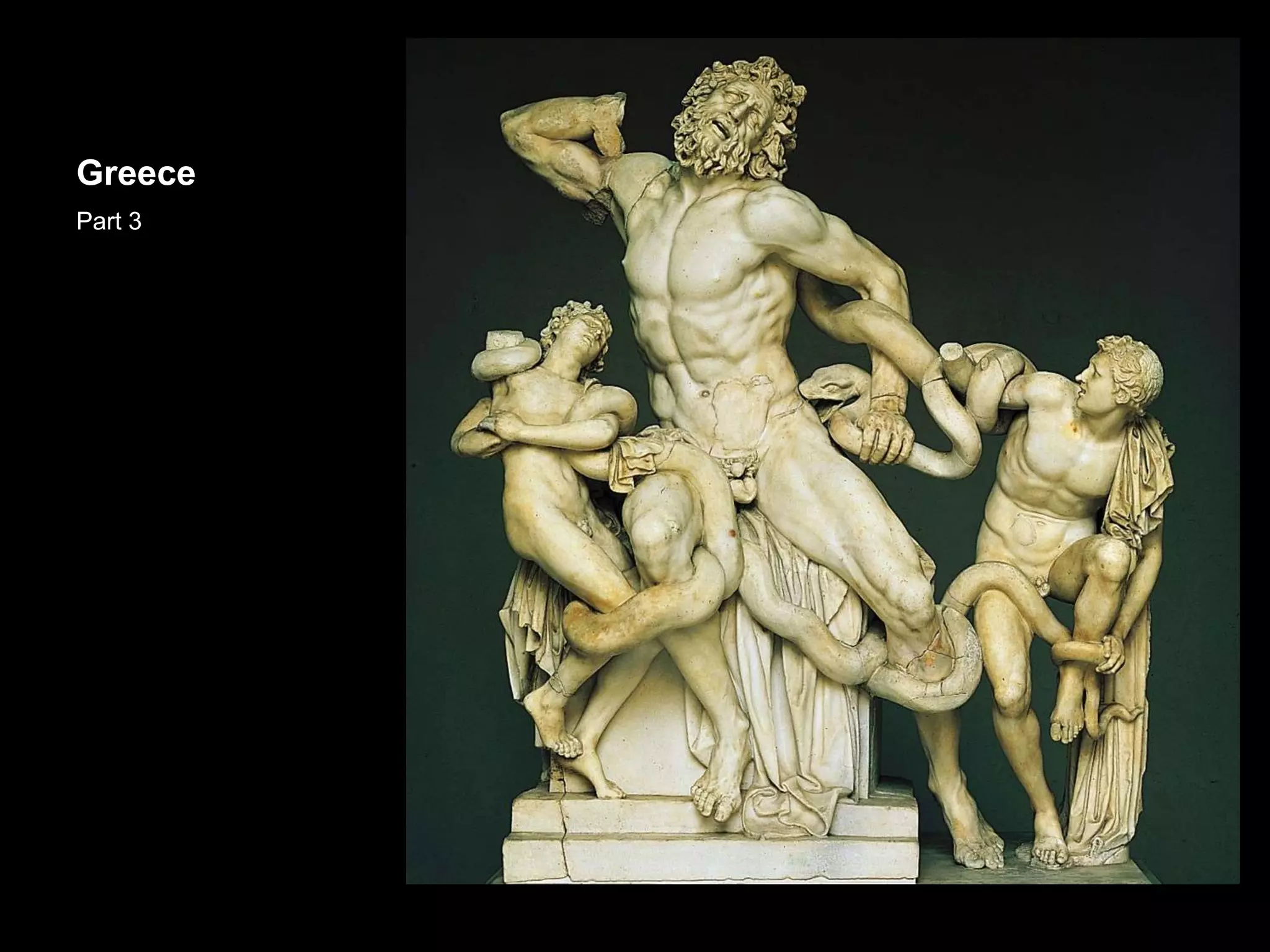

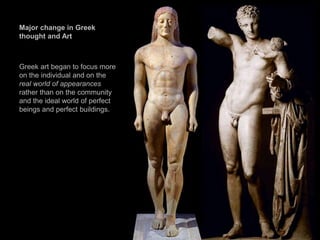

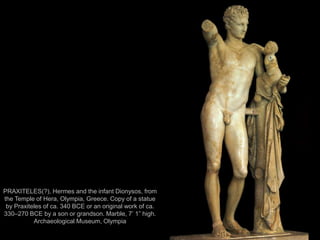

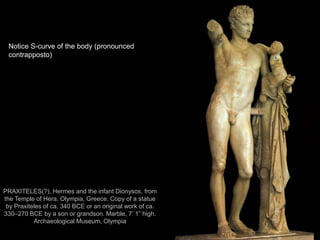

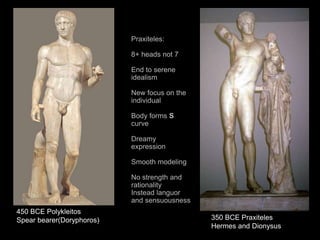

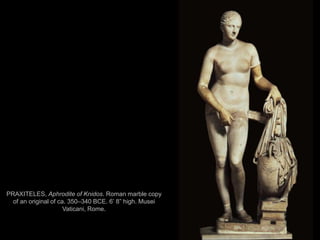

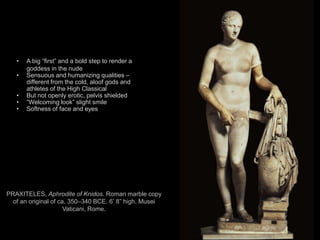

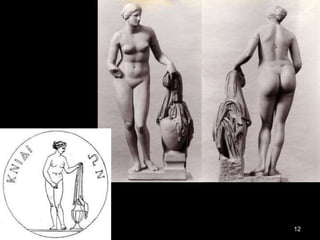

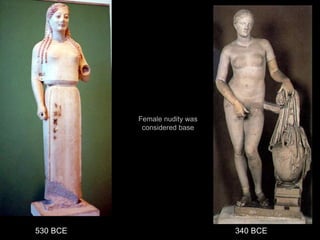

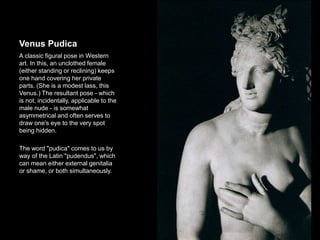

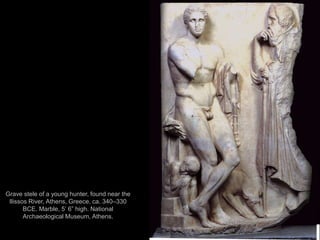

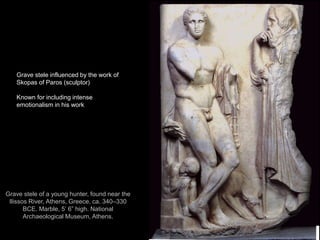

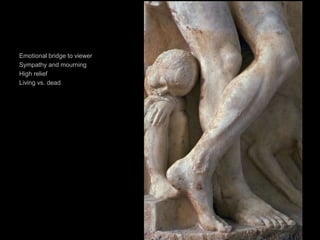

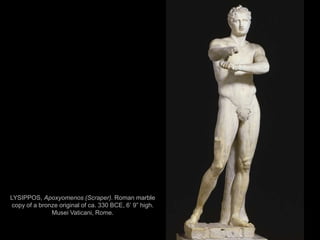

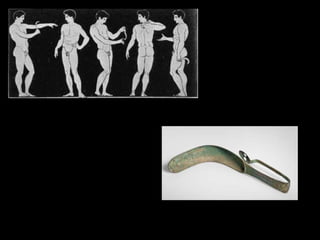

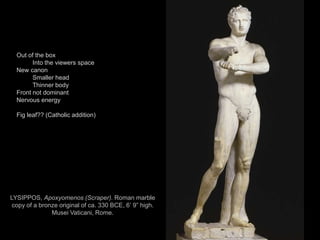

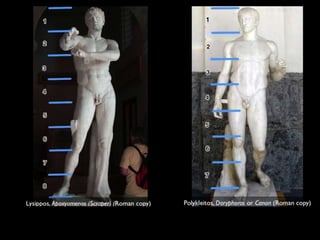

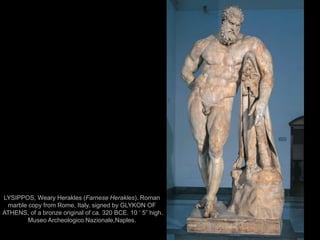

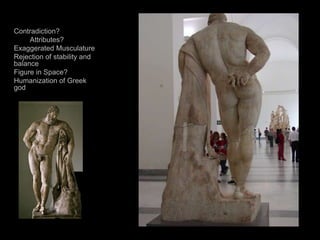

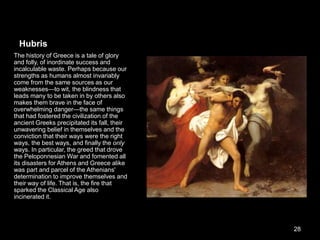

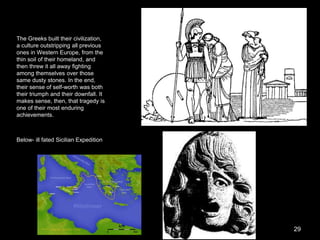

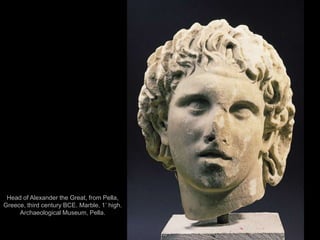

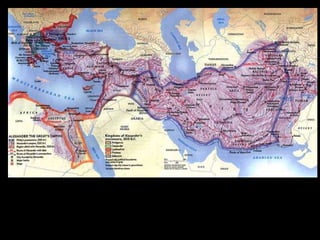

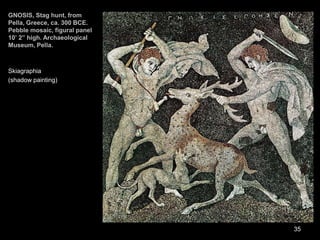

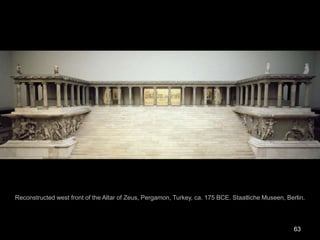

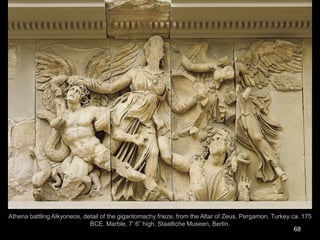

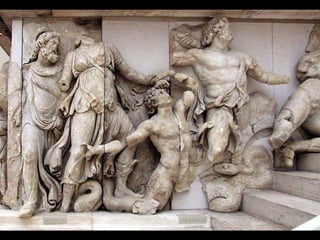

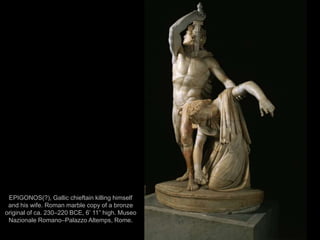

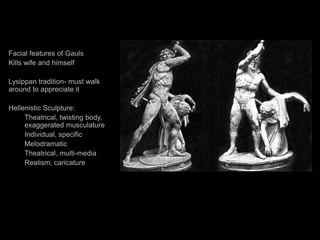

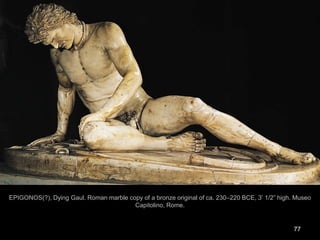

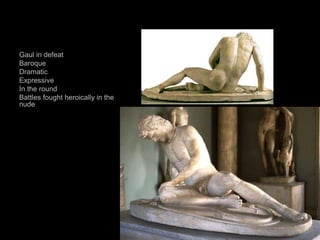

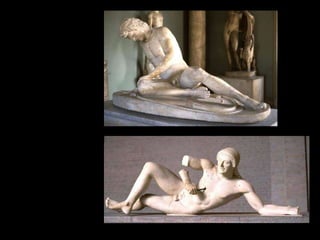

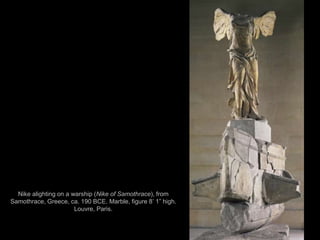

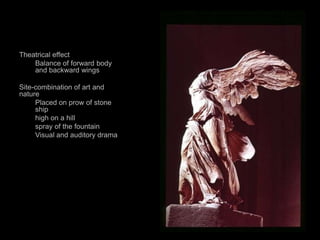

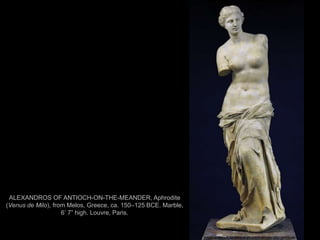

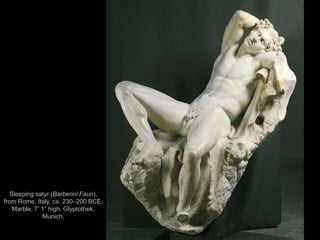

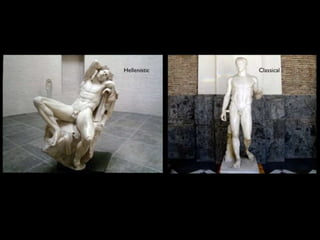

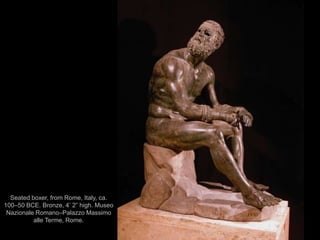

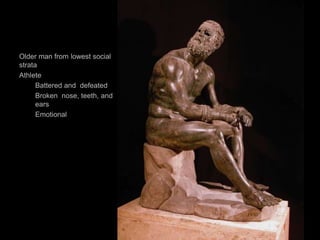

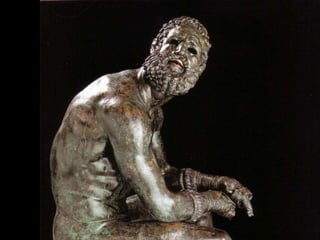

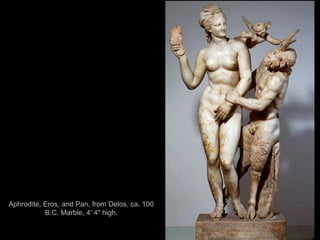

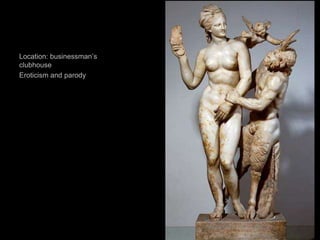

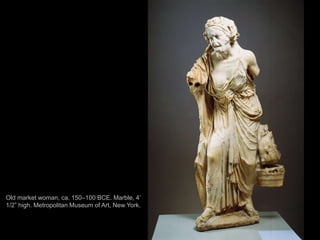

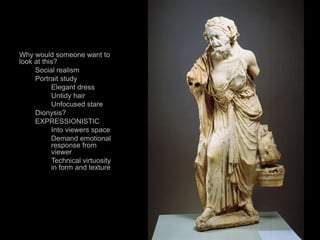

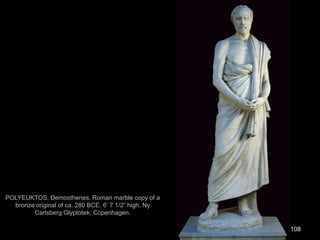

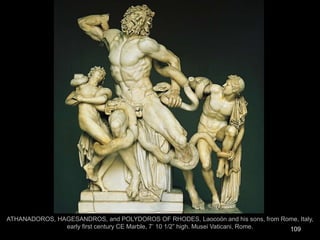

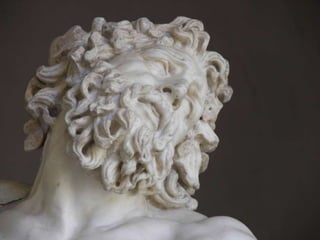

The document summarizes major developments in Greek art and thought during the Late Classical period (404-338 BCE) following the Peloponnesian War. It discusses how Greek art began to focus more on realism and individual subjects rather than idealism. Key artists from this period like Praxiteles and Lysippos are mentioned for introducing naturalism, emotion, and contrapposto poses into their sculptures. The Hellenistic period that followed is summarized as a time of cultural blending and the rise of new dynastic states after Alexander the Great's conquests.