This document summarizes a presentation on curve fitting using GraphPad Prism. It discusses nonlinear regression techniques for analyzing dose-response and binding curve data commonly used by biologists. Specific nonlinear regression models like sigmoidal dose-response curves are described. The document provides guidance on choosing and fitting appropriate models, evaluating model fit, and improving model fit if needed.

![3/29/2010

2

NIAID Site License

http://graphpad.com/paasl/index.cfm?sitecode=NIHNIAID

http://bioinformatics.niaid.nih.gov/

Nonlinear Regression

• Statistical technique commonly used for log dose s response

q y

curve‐fitting by biologists at NIAID

– Dose‐response studies

– Protein binding experiments

• Nonlinear regression is rarely studied in

statistics coursework

Sometimes mentioned briefl in a regression

log-dose vs response

-10 -8 -6 -4 -2

-100

0

100

200

300

400

500

No inhibitor

Inhibitor

log[Dose]

Response

dose vs. response

– Sometimes mentioned briefly in a regression

or linear models course

• Nonlinear regression is sometimes

omitted from statistical software or

poorly executed in software packages

0.0000 0.0001 0.0002 0.0003 0.0004

0

100

200

300

400

500

No inhibitor

Inhibitor

Dose

Response](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/curve-fitting04012010-170503181727/85/GraphPad-Prism-Curve-fitting-2-320.jpg)

![3/29/2010

7

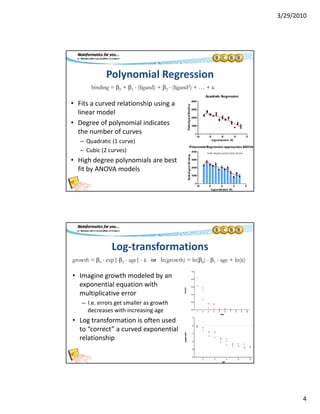

Dose‐Response Models

• Most commonly used model

among NIAID researchers

log-dose vs response

500

• Up to five parameters

– TOP and BOTTOM

– Log(EC50)

– Hillslope (default = 1)

– Symmetry (default = 1)

-10 -8 -6 -4 -2

-100

0

100

200

300

400

500

No inhibitor

Inhibitor

log[Agonist], M

• Concepts presented for dose‐

response models will apply to all

other nonlinear models Response Bottom

Top Bottom

110 logEC50logX Hillslope

Getting Started in PRISM

• Open a XY data table and

enter data

• Transform and normalize

data if necessary

• Open the nonlinear fit

menu in PRISM](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/curve-fitting04012010-170503181727/85/GraphPad-Prism-Curve-fitting-7-320.jpg)

![3/29/2010

8

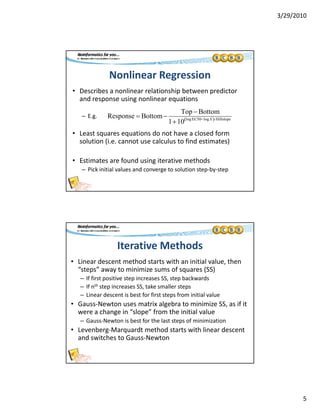

Why Use log(X) For Sigmoid Dose Response?

• Raw X values produce a

dose vs. response

500

Raw X values produce a

hyperbolic curve

– Large errors at the ascent

– Small errors at the plateau

• Log(X) values produce a log dose vs response

0.0000 0.0001 0.0002 0.0003 0.0004

0

100

200

300

400

No inhibitor

Inhibitor

Dose

Response

sigmoid “esse” curve

– Moderate errors throughout

– Best estimates of EC50

log-dose vs response

-10 -8 -6 -4 -2

-100

0

100

200

300

400

500

No inhibitor

Inhibitor

log[Dose]

Response

Importance of Log Transform](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/curve-fitting04012010-170503181727/85/GraphPad-Prism-Curve-fitting-8-320.jpg)