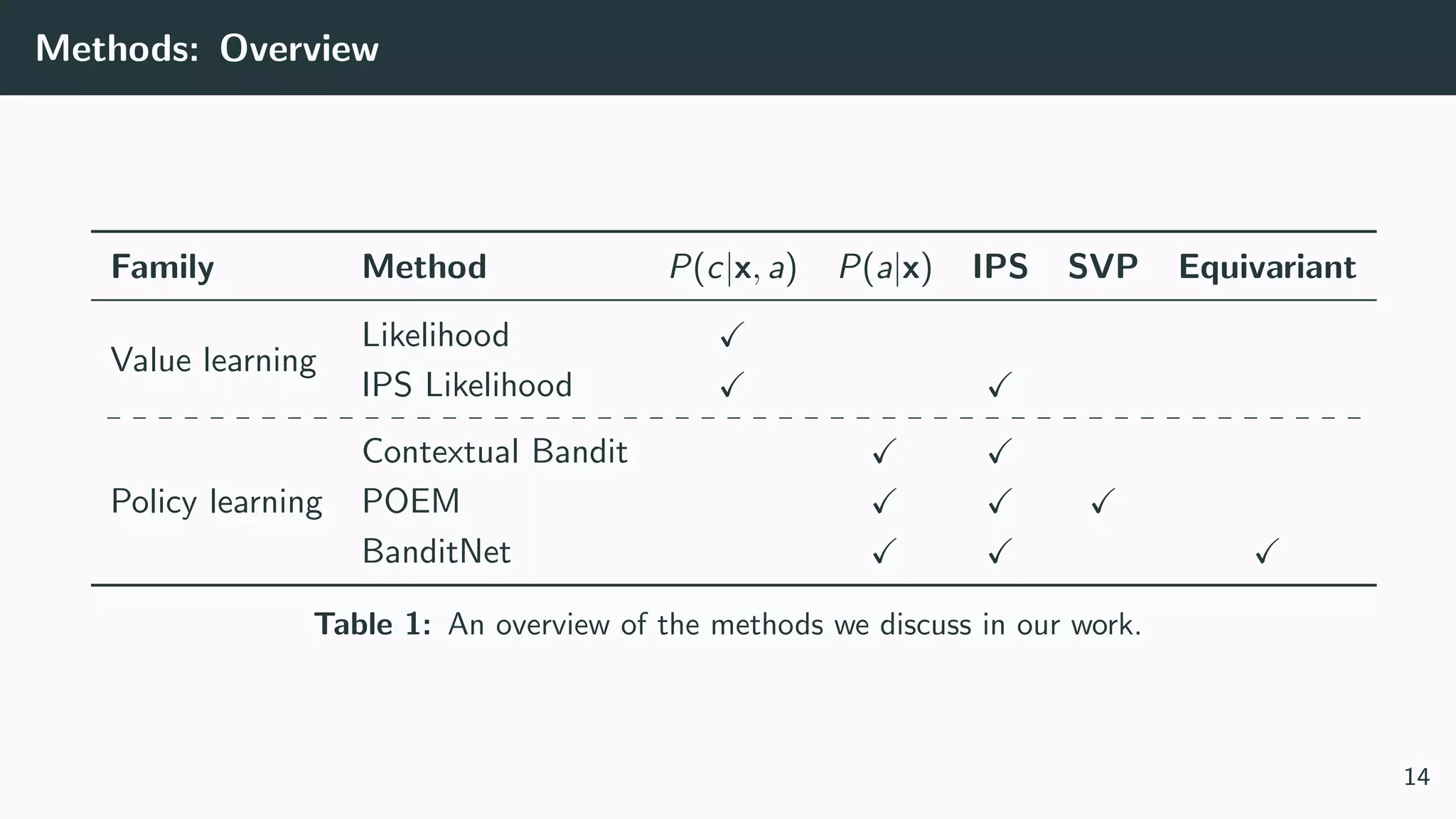

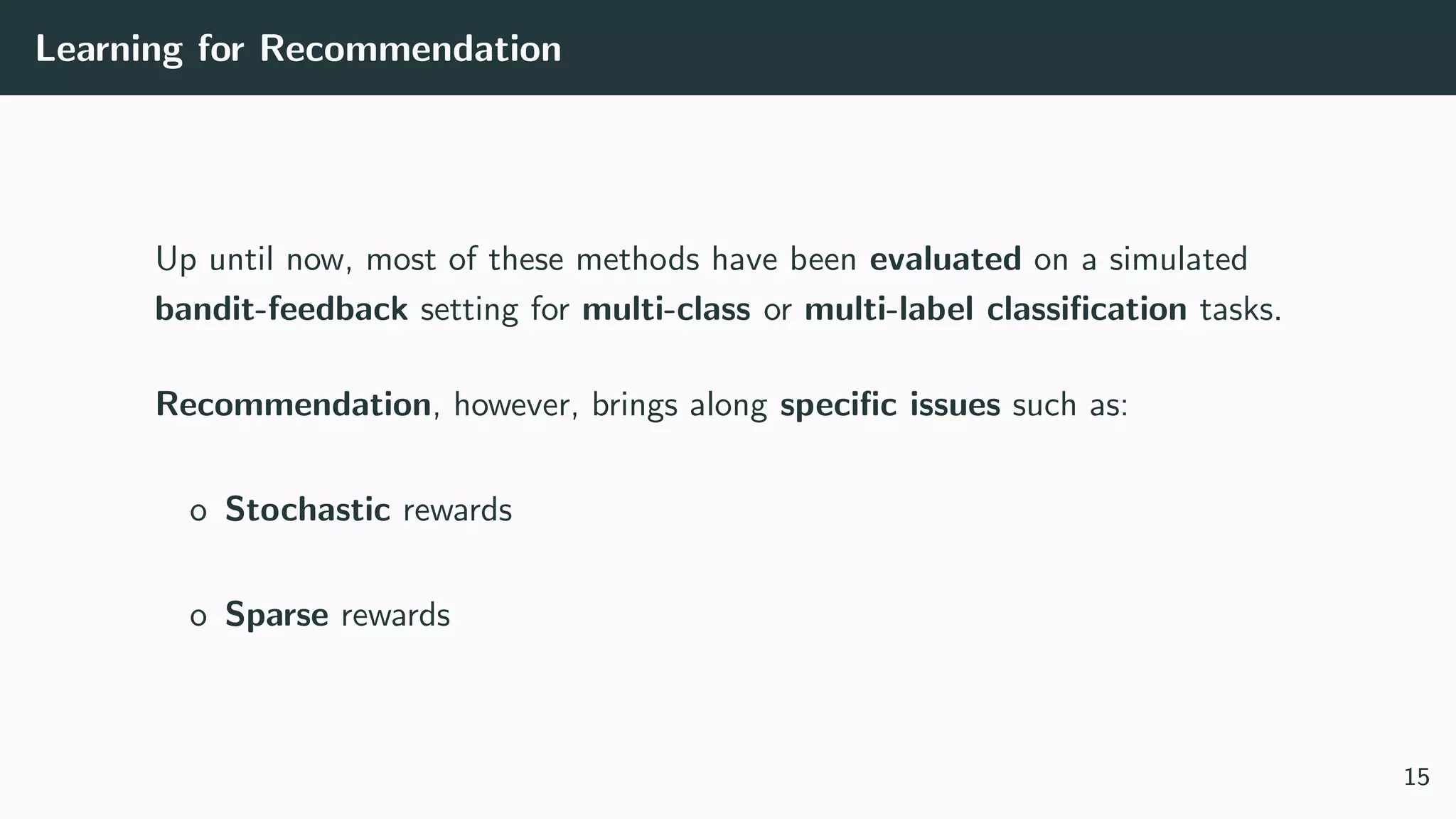

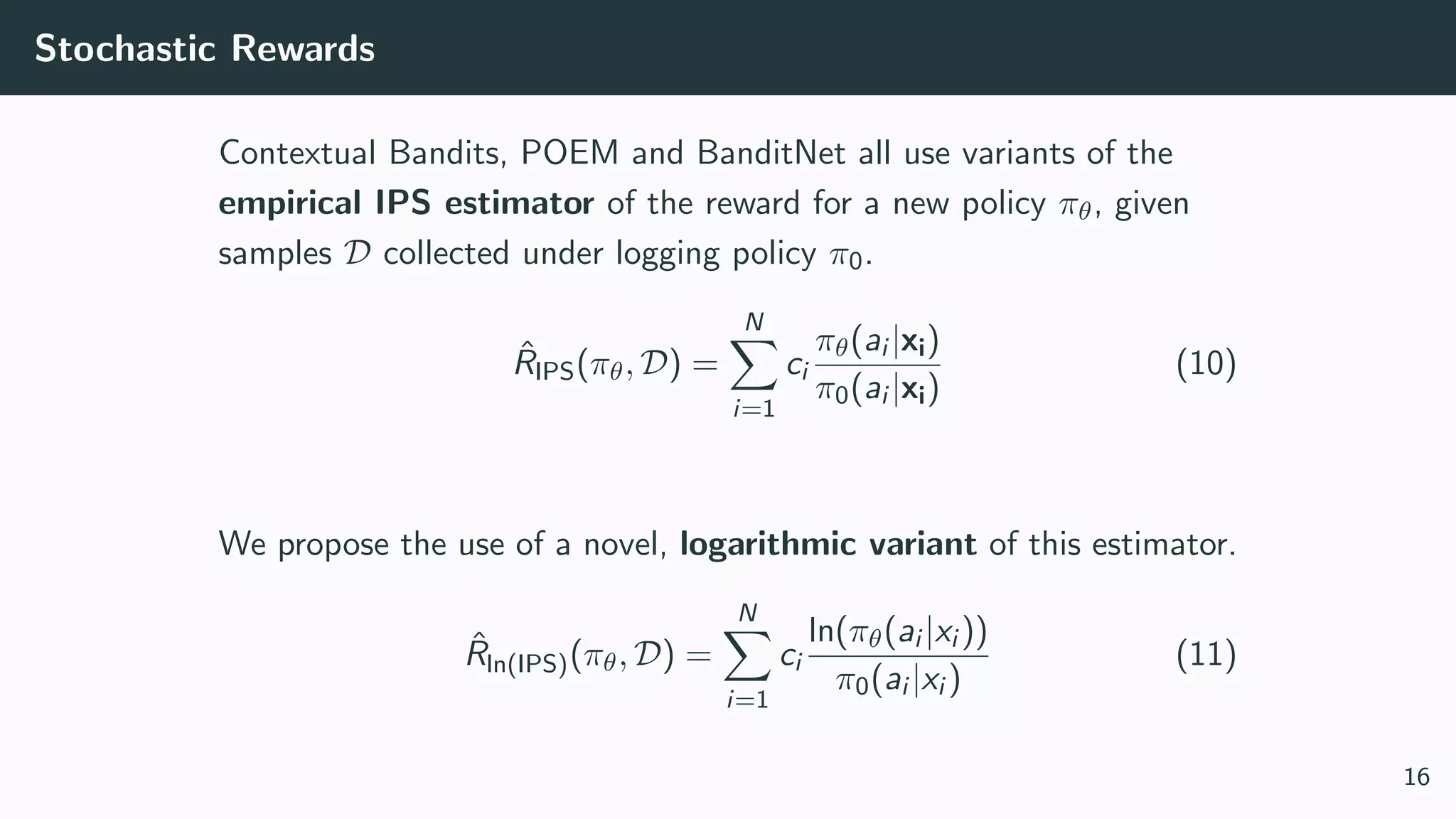

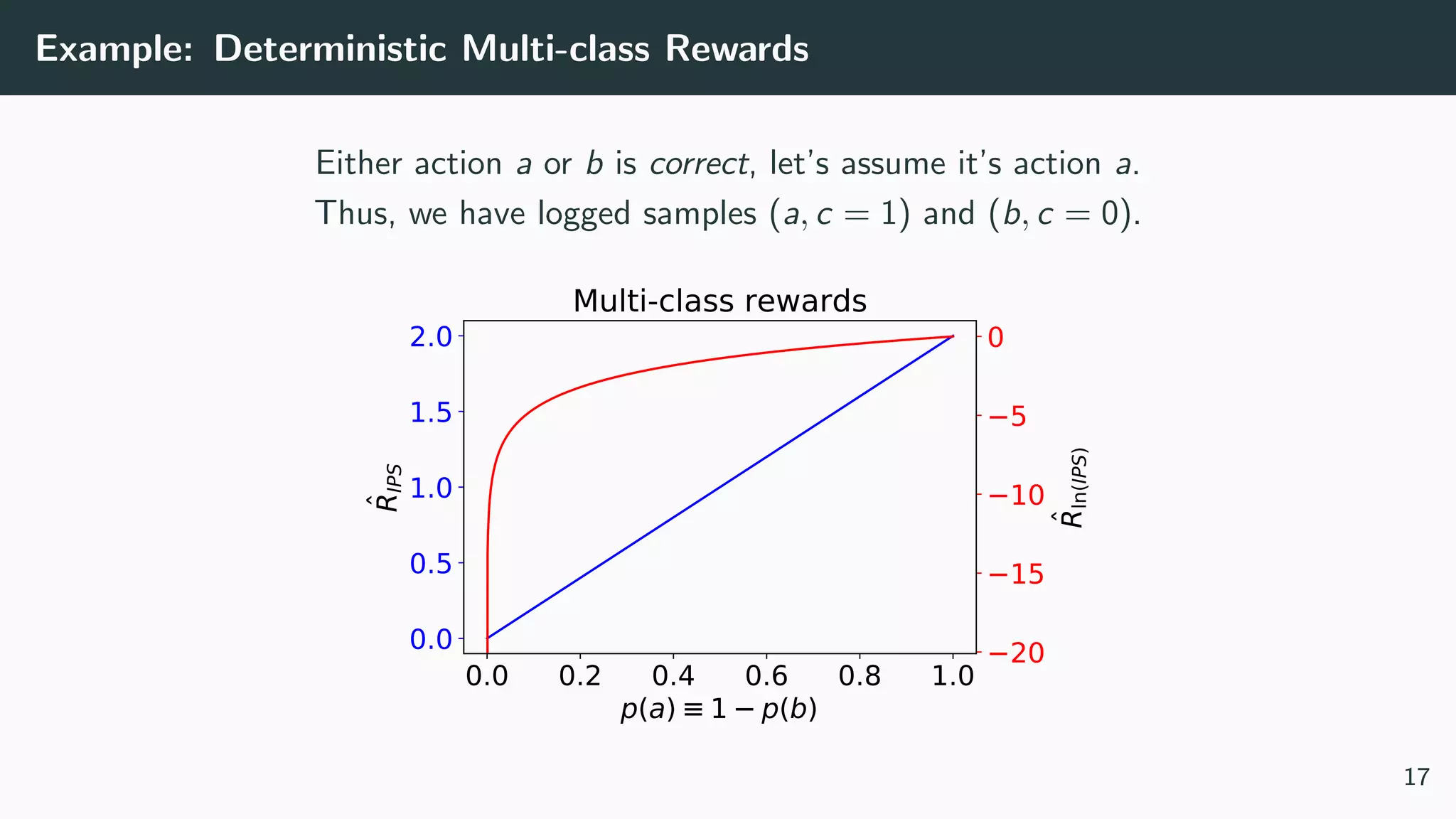

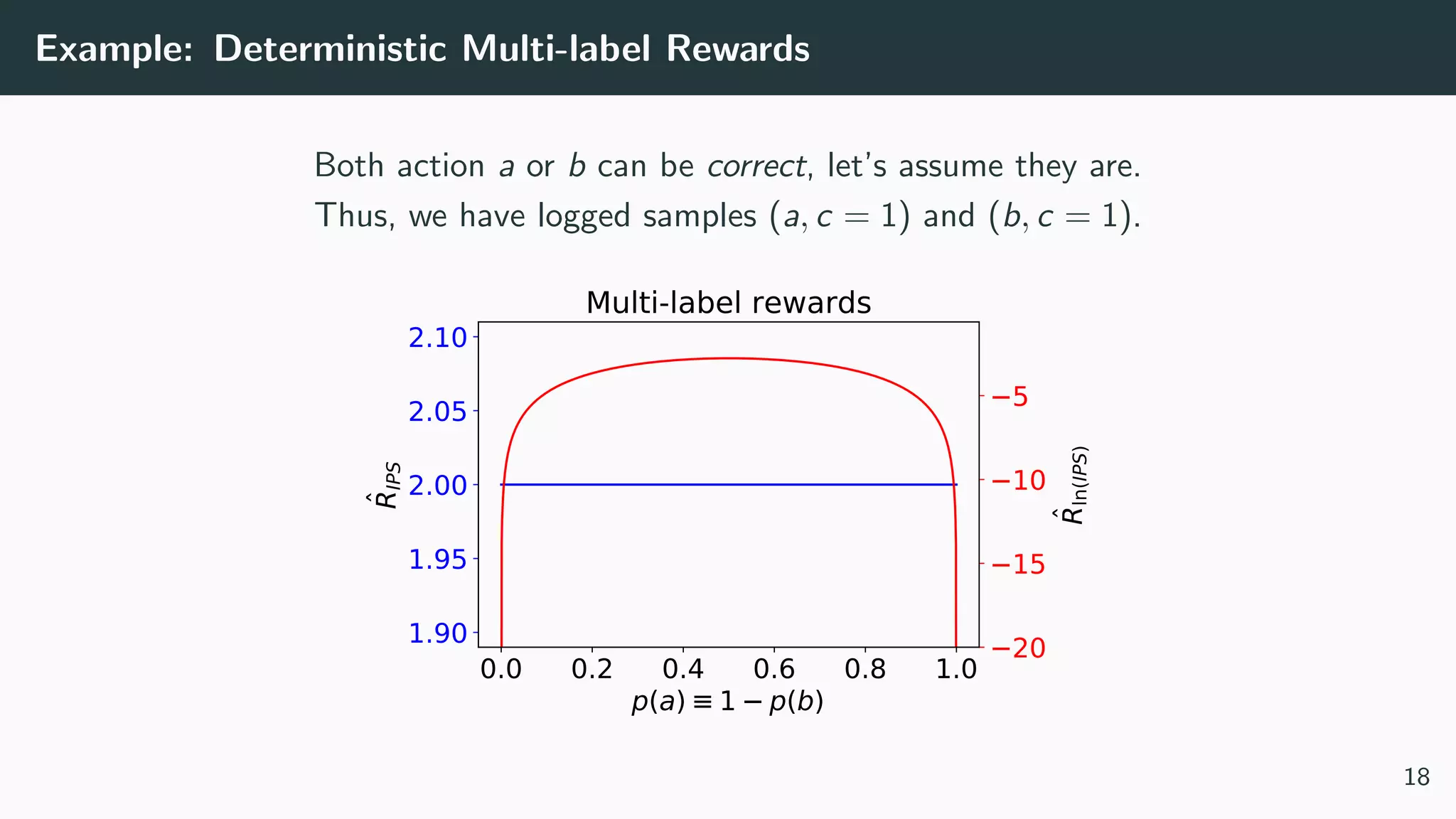

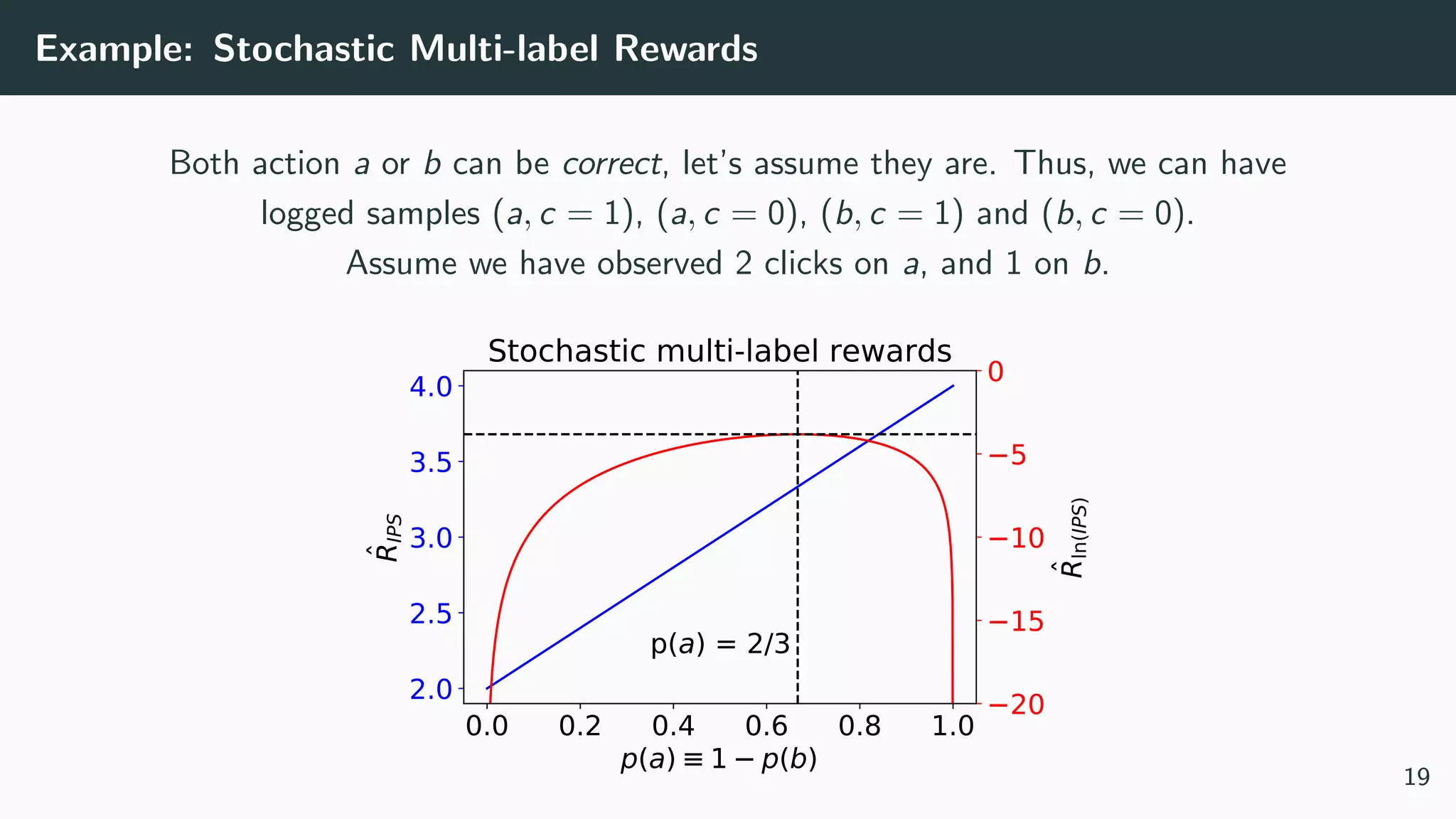

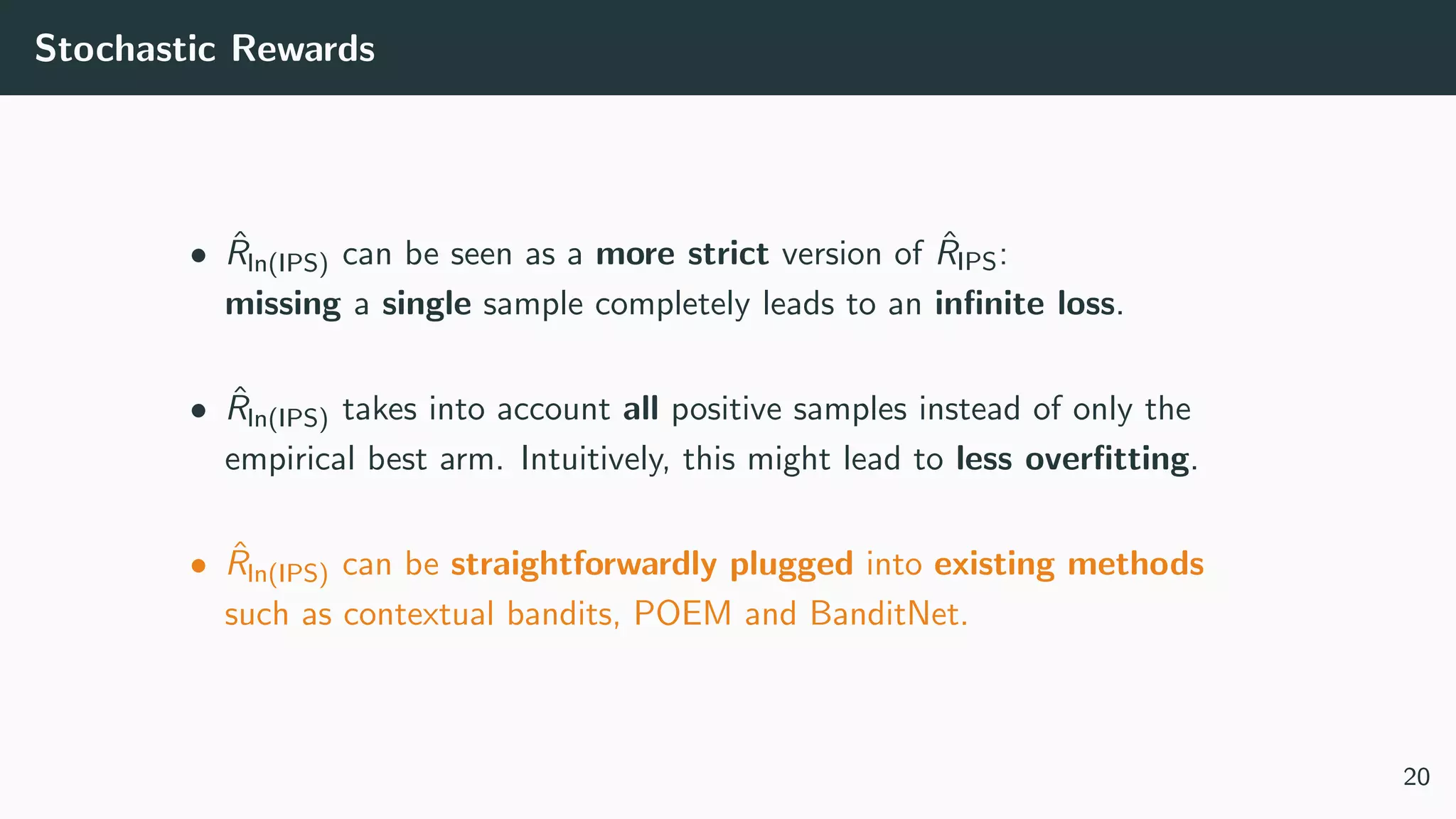

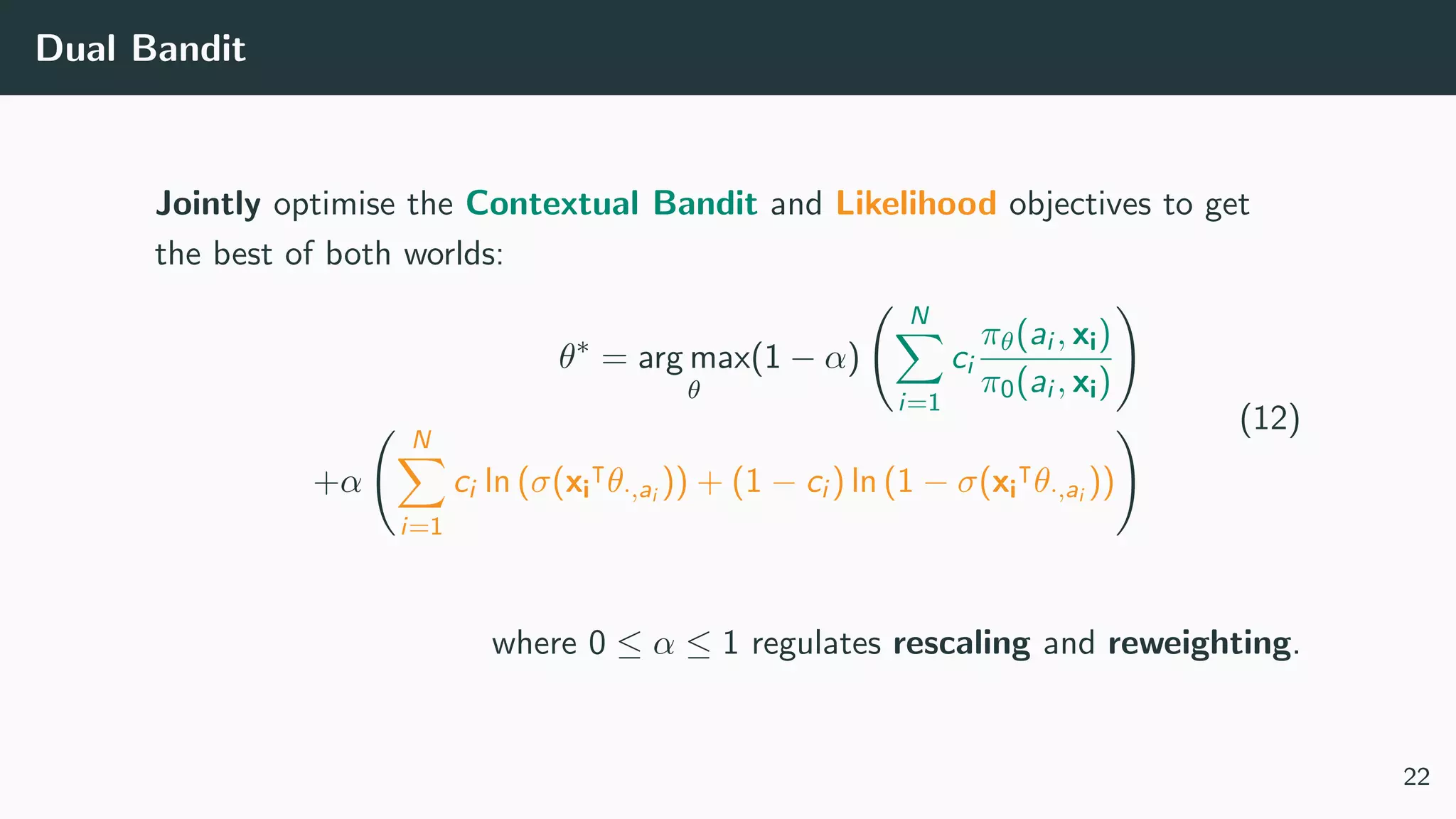

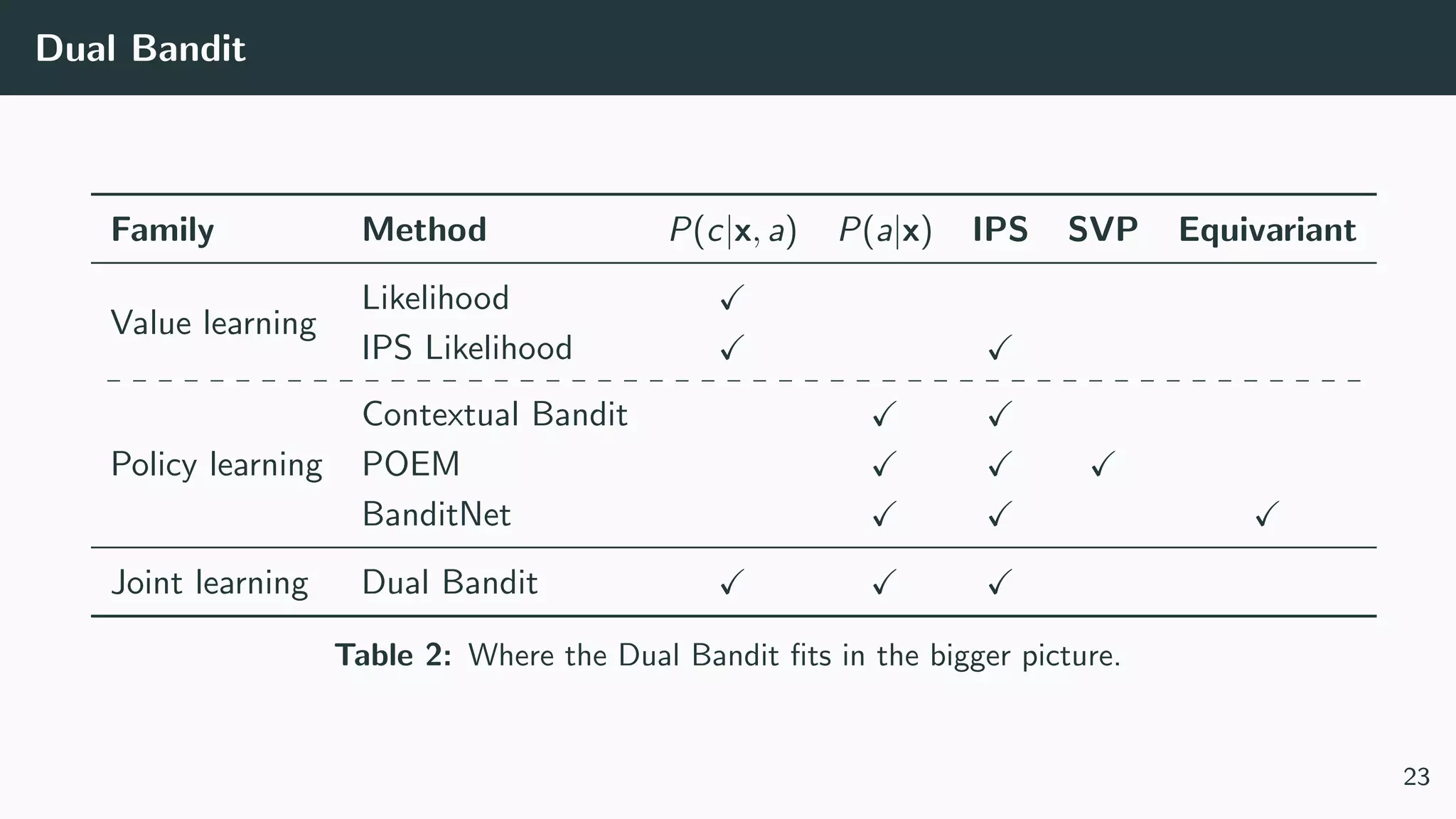

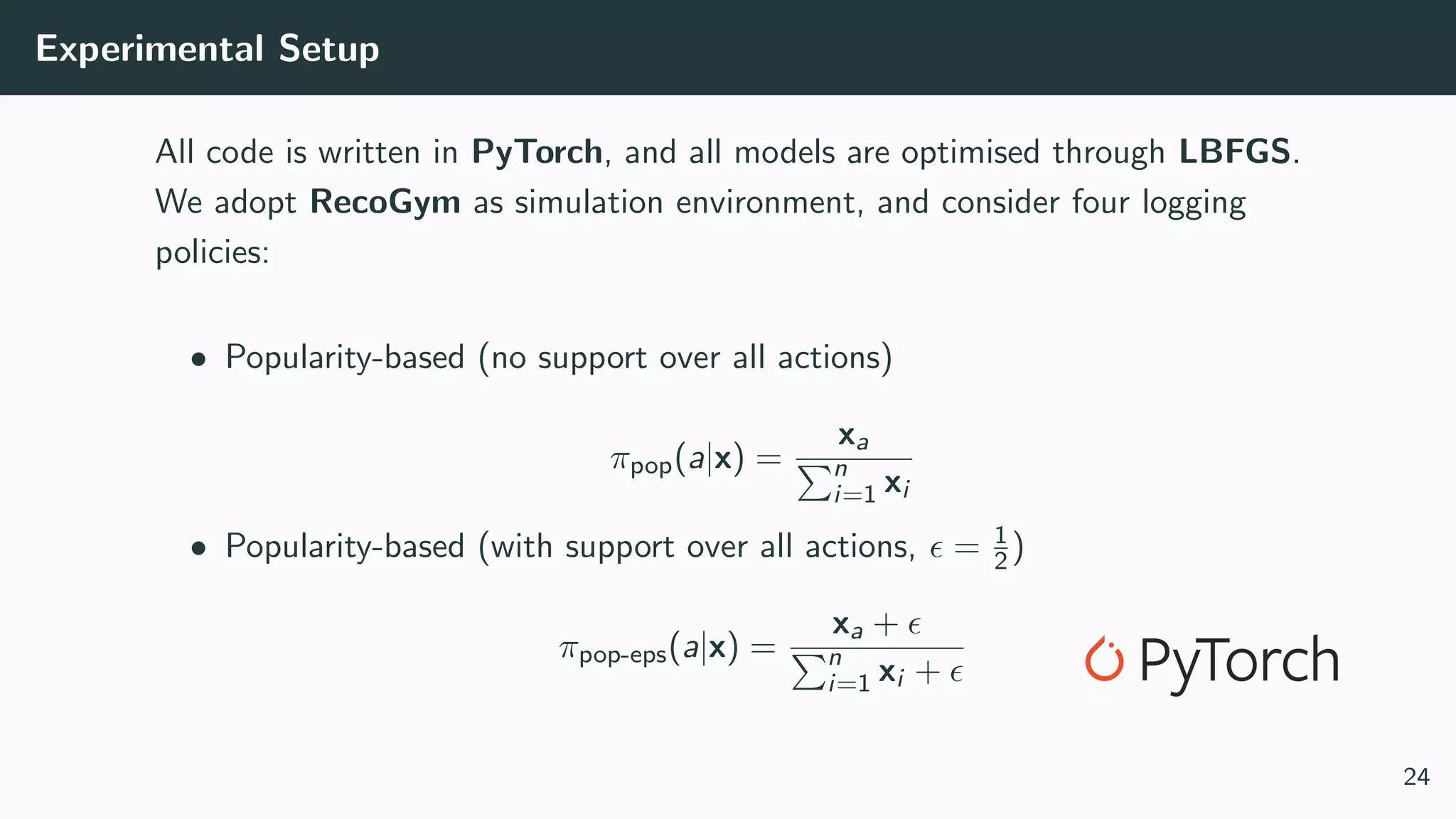

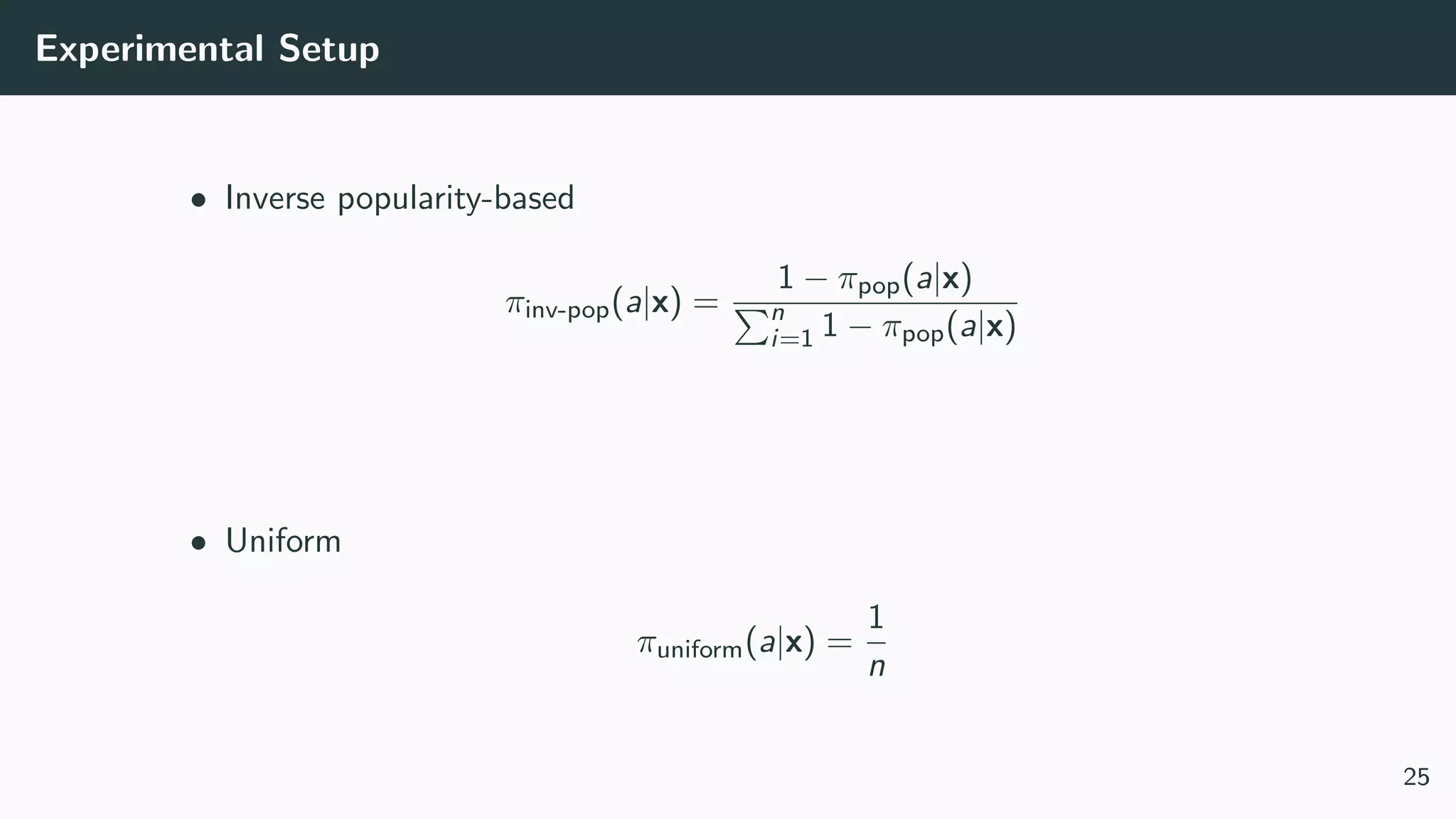

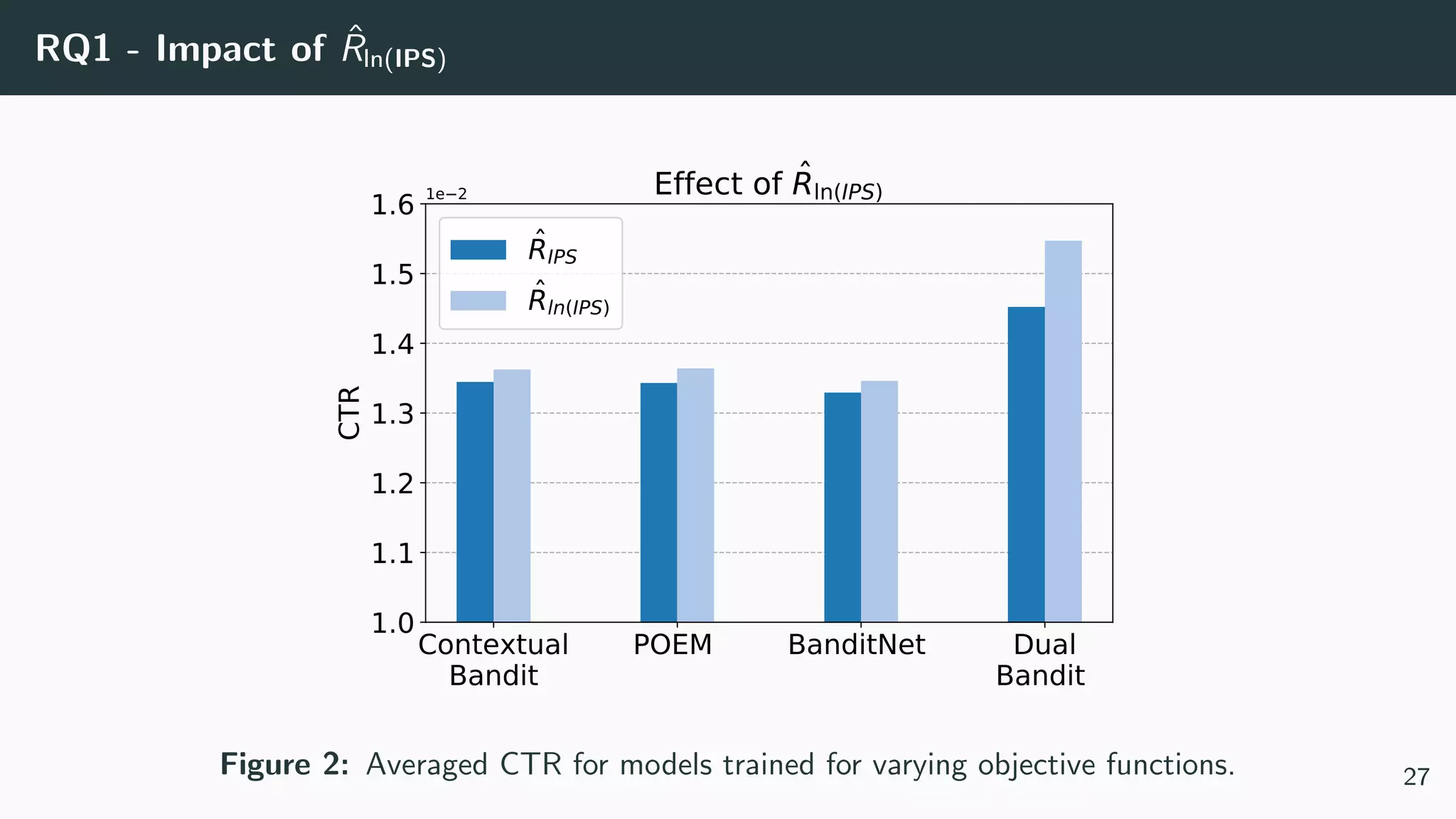

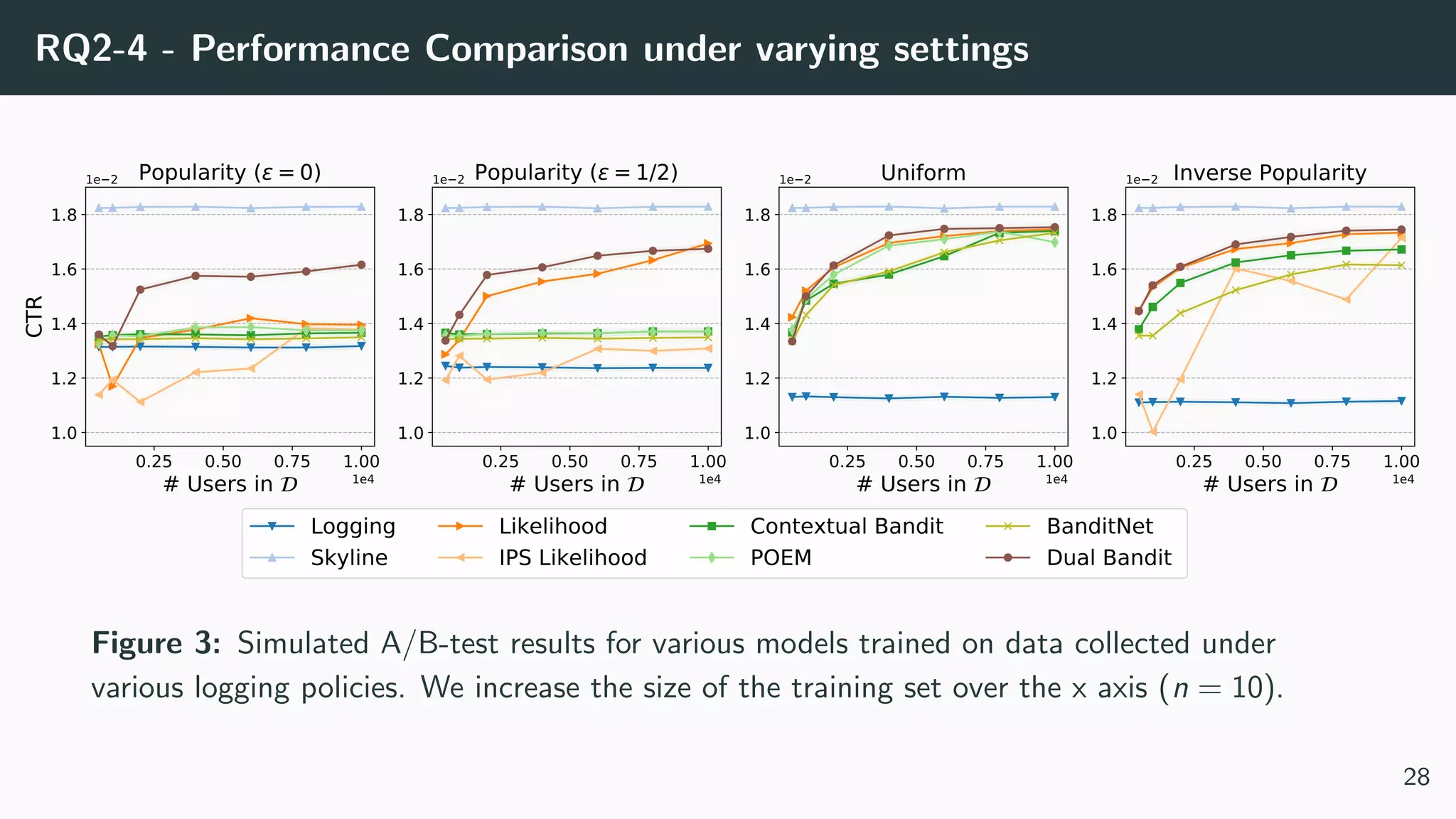

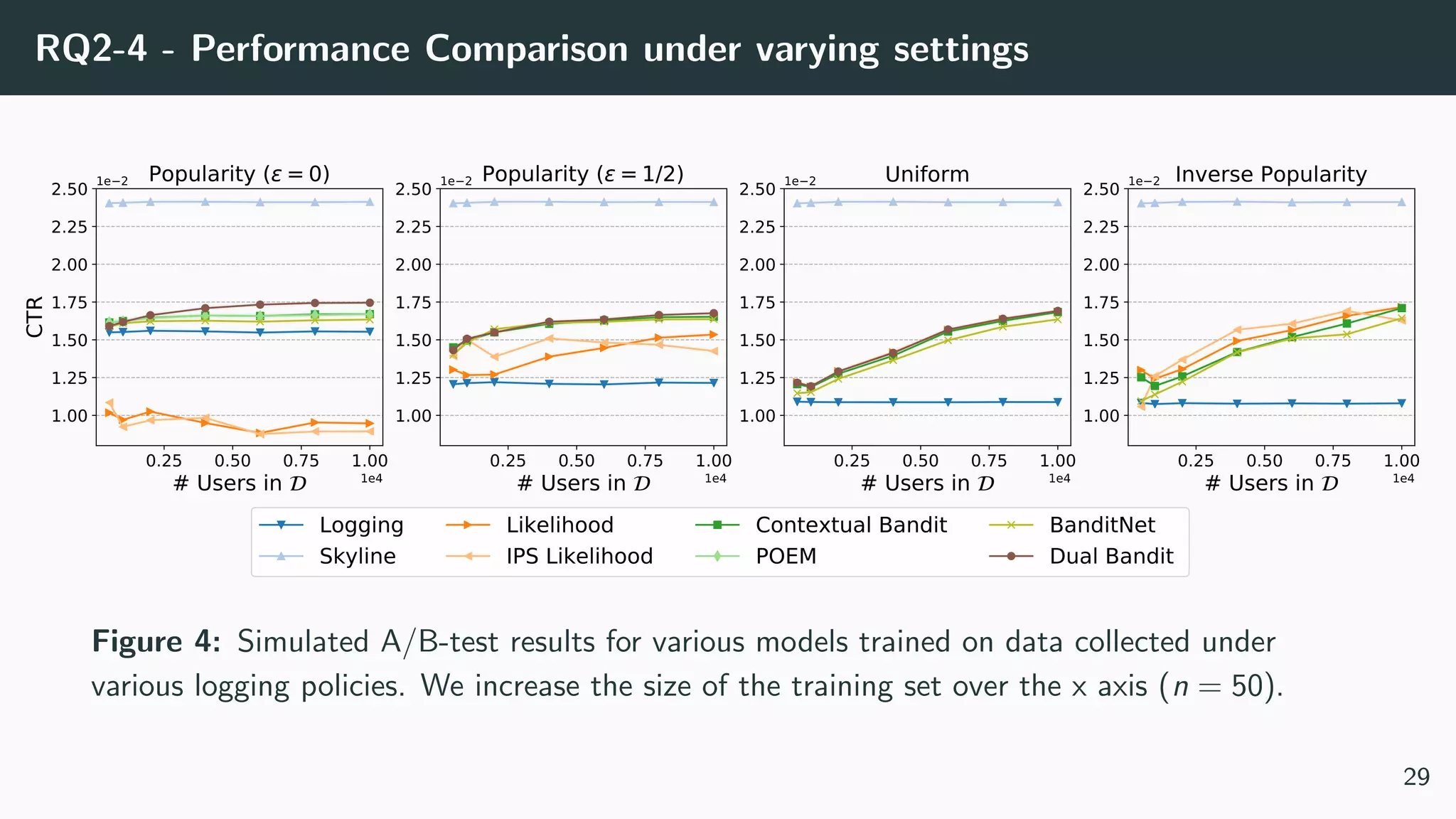

This document discusses counterfactual learning methods aimed at improving recommendation systems by directly learning from logged user feedback rather than relying on traditional collaborative filtering techniques. It introduces various methods, such as the dual bandit approach, which optimize recommendations by combining contextual bandit strategies with value-based learning to handle challenges like stochastic and sparse rewards. Empirical experiments demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed methods in improving recommendation performance across different logging policies.

![Background

Notation

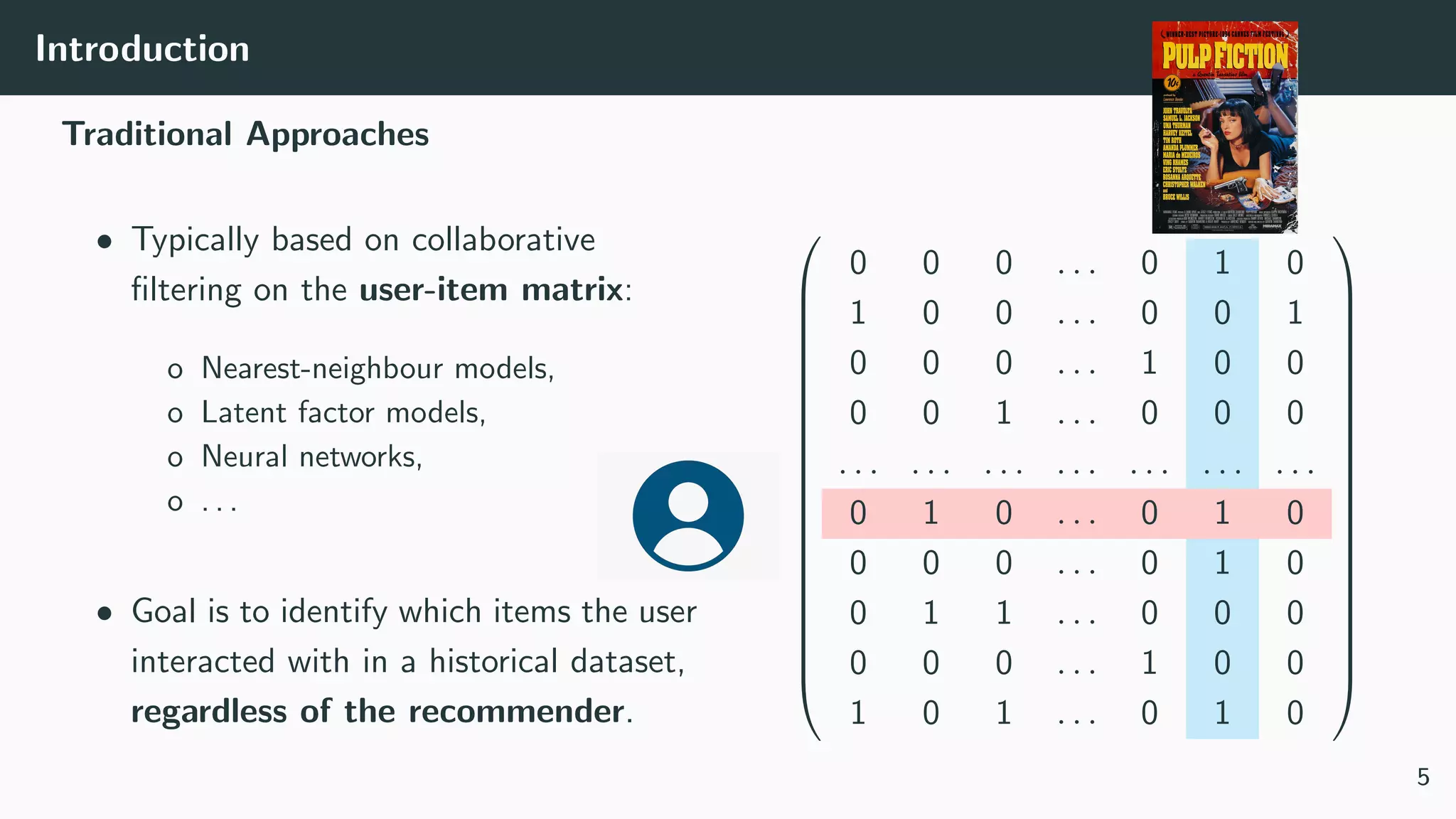

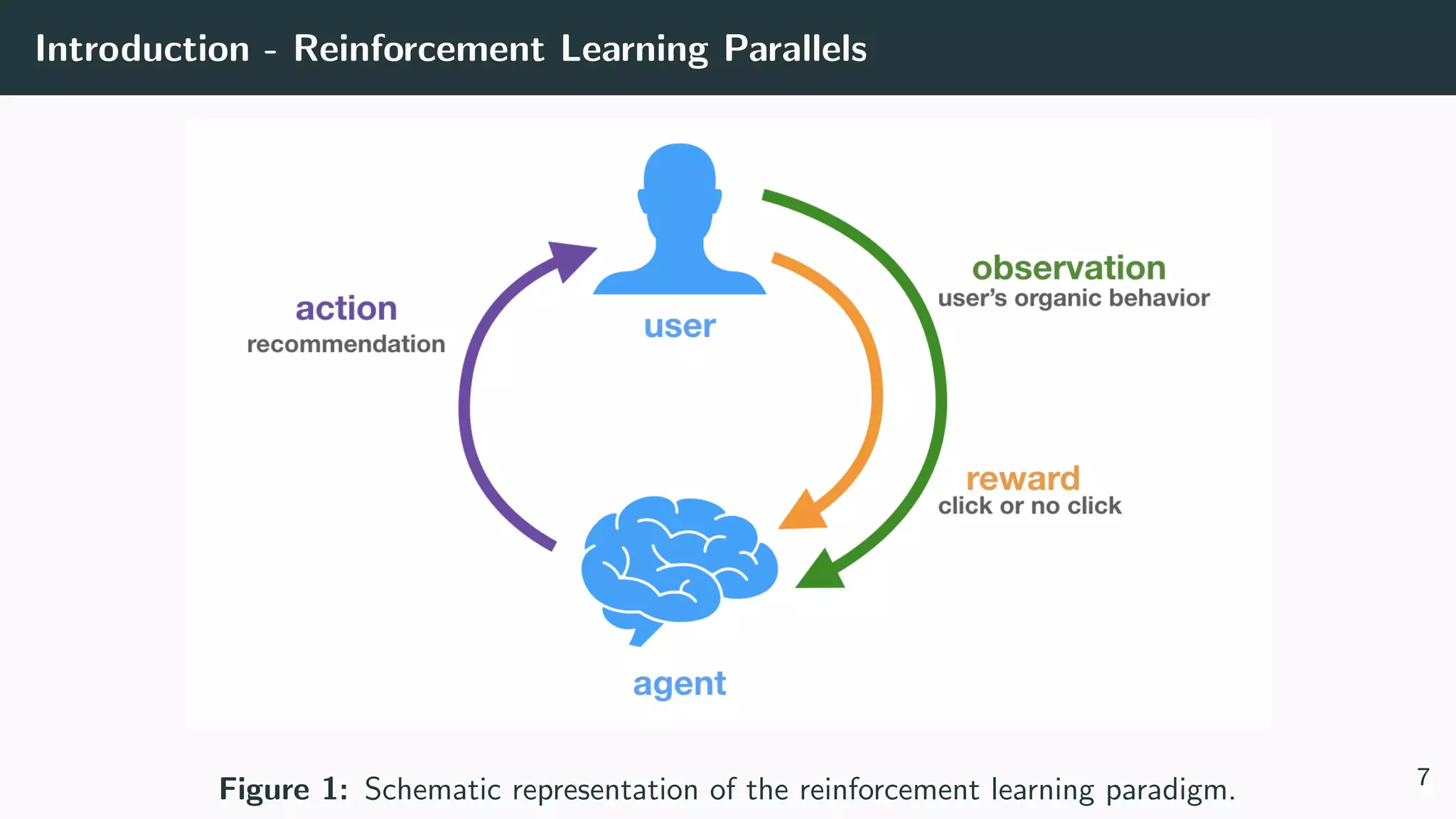

We assume:

• A stochastic logging policy π0 that describes a probability distribution

over actions, conditioned on the context.

• Dataset of logged feedback D with N tuples (x, a, p, c) with

x ∈ Rn a context vector (historical counts),

a ∈ [1, n] an action identifier,

p ≡ π0(a|x) the logging propensity,

c ∈ {0, 1} the observed reward (click).

8](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dsmeetupleuven25092019-190926161559/75/Counterfactual-Learning-for-Recommendation-10-2048.jpg)

![Methods: Value-based

Likelihood (Logistic Regression) Hosmer Jr. et al. [2013]

Model the probability of a click, conditioned on the action and context:

P(c = 1|x, a) (1)

You can optimise your favourite classifier for this! (e.g. Logistic Regression)

Obtain a decision rule from:

a∗

= arg max

a

P(c = 1|x, a). (2)

9](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dsmeetupleuven25092019-190926161559/75/Counterfactual-Learning-for-Recommendation-11-2048.jpg)

![Methods: Value-based

IPS-weighted Likelihood Storkey [2009]

Naturally, as the logging policy is trying to achieve some goal (e.g. clicks,

views, dwell time, . . . ), it will take some actions more often than others.

We can use Inverse Propensity Scoring (IPS) to force the error of the fit

to be distributed evenly across the action space.

Reweight samples (x, a) by:

1

π0(a|x)

(3)

10](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dsmeetupleuven25092019-190926161559/75/Counterfactual-Learning-for-Recommendation-12-2048.jpg)

![Methods: Policy-based

Contextual Bandit Bottou et al. [2013]

Model the counterfactual reward:

“How many clicks would a policy πθ have gotten if it was deployed instead of π0?”

Directly optimise πθ, with θ ∈ Rn×n the model parameters:

P(a|x, θ) = πθ(a|x) (4)

θ∗

= arg max

θ

N

i=1

ci

πθ(ai |xi)

π0(ai |xi)

(5)

a∗

= arg max

a

P(a|x, θ) (6)

11](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dsmeetupleuven25092019-190926161559/75/Counterfactual-Learning-for-Recommendation-13-2048.jpg)

![Methods: Policy-based

POEM Swaminathan and Joachims [2015a]

IPS estimators tend to have high variance, clip weights and introduce

sample variance penalisation:

θ∗

= arg max

θ

1

N

N

i=1

ci min M,

πθ(ai |xi)

π0(ai |xi)

− λ

Varθ

N

(7)

12](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dsmeetupleuven25092019-190926161559/75/Counterfactual-Learning-for-Recommendation-14-2048.jpg)

![Methods: Policy-based

NormPOEM Swaminathan and Joachims [2015b]

Variance penalisation is insufficient, use the self-normalised IPS estimator:

θ∗

= arg max

θ

N

i=1 ci

πθ(ai |xi)

π0(ai |xi)

N

i=1

πθ(ai |xi)

π0(ai |xi)

− λ

Varθ

N

(8)

BanditNet Joachims et al. [2018]

Equivalent to a certain optimal translation of the reward:

θ∗

= arg max

θ

N

i=1

(ci − γ)

πθ(ai |xi)

π0(ai |xi)

(9)

13](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dsmeetupleuven25092019-190926161559/75/Counterfactual-Learning-for-Recommendation-15-2048.jpg)