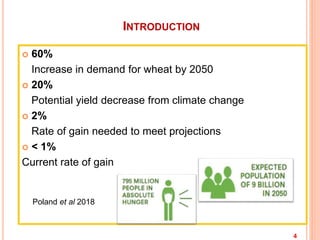

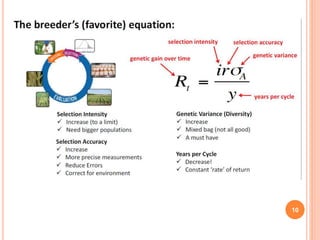

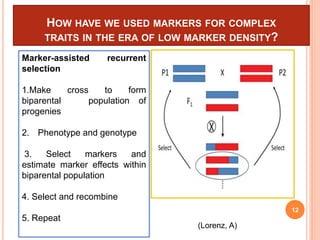

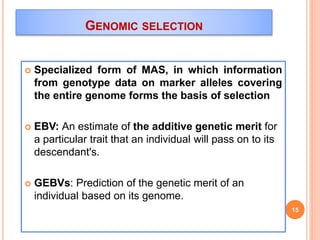

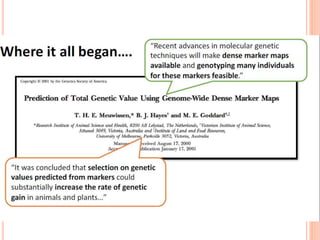

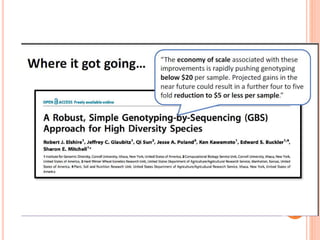

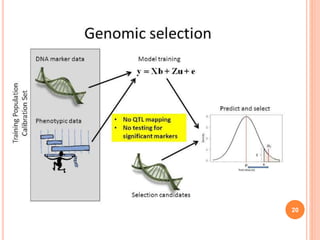

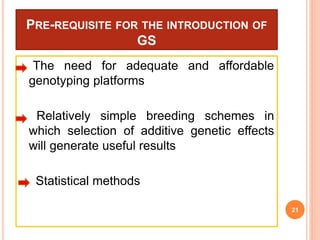

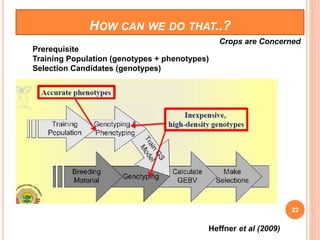

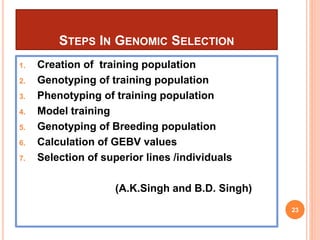

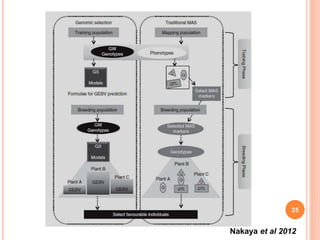

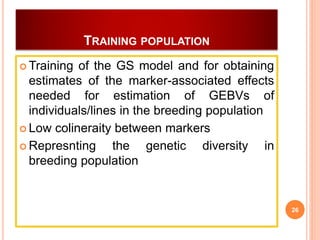

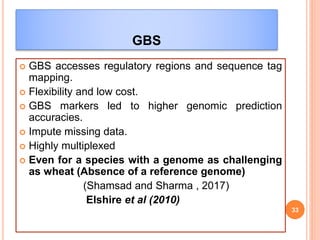

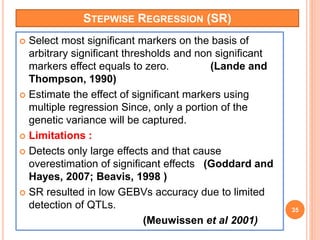

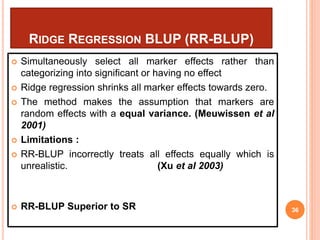

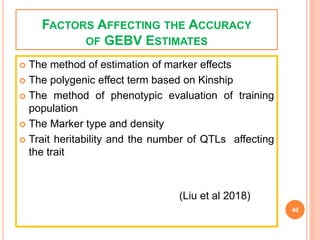

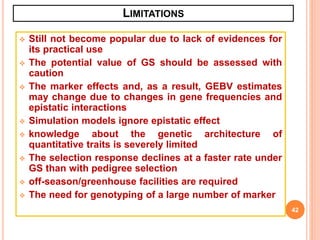

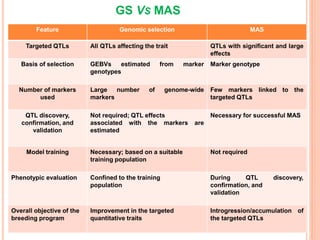

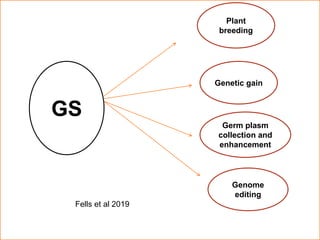

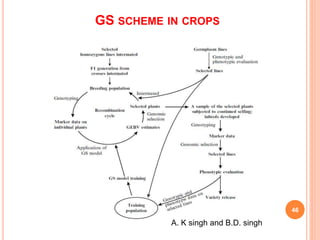

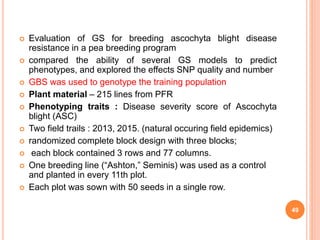

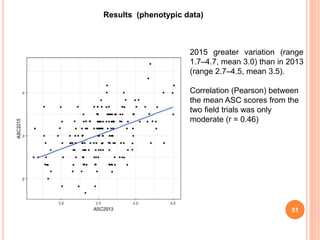

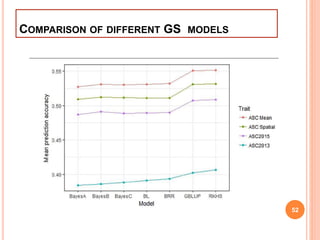

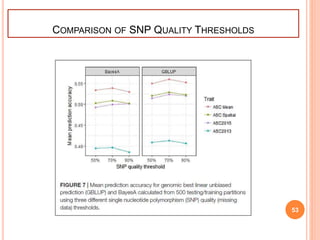

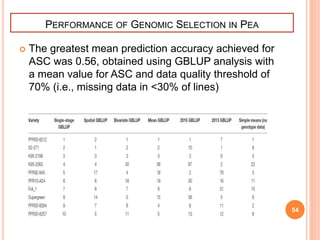

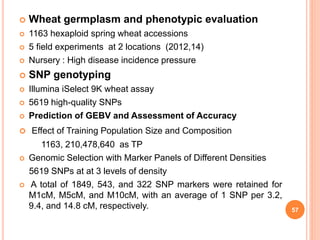

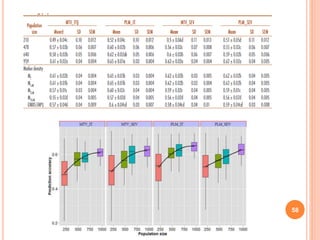

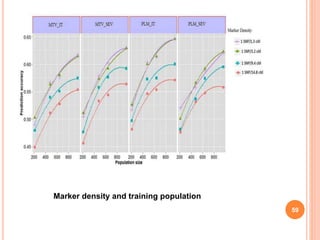

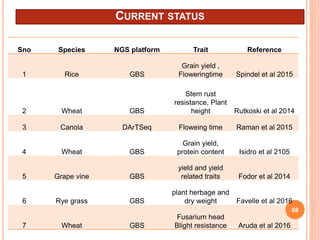

This document provides an introduction to genomic selection for crop improvement. It discusses how genomic selection works and the steps involved, including creating a training population, genotyping and phenotyping the training population, model training, genotyping the breeding population, calculating genomic estimated breeding values, and making selection decisions. Some advantages of genomic selection are greater genetic gains per unit of time compared to phenotypic selection and the ability to select for low heritability traits. Factors that can affect the accuracy of genomic predicted breeding values include the prediction model used, population size, marker density and type, trait heritability, and number of causal variants. Genomic selection is being applied to plant breeding programs for traits like disease resistance and yield to help meet future food