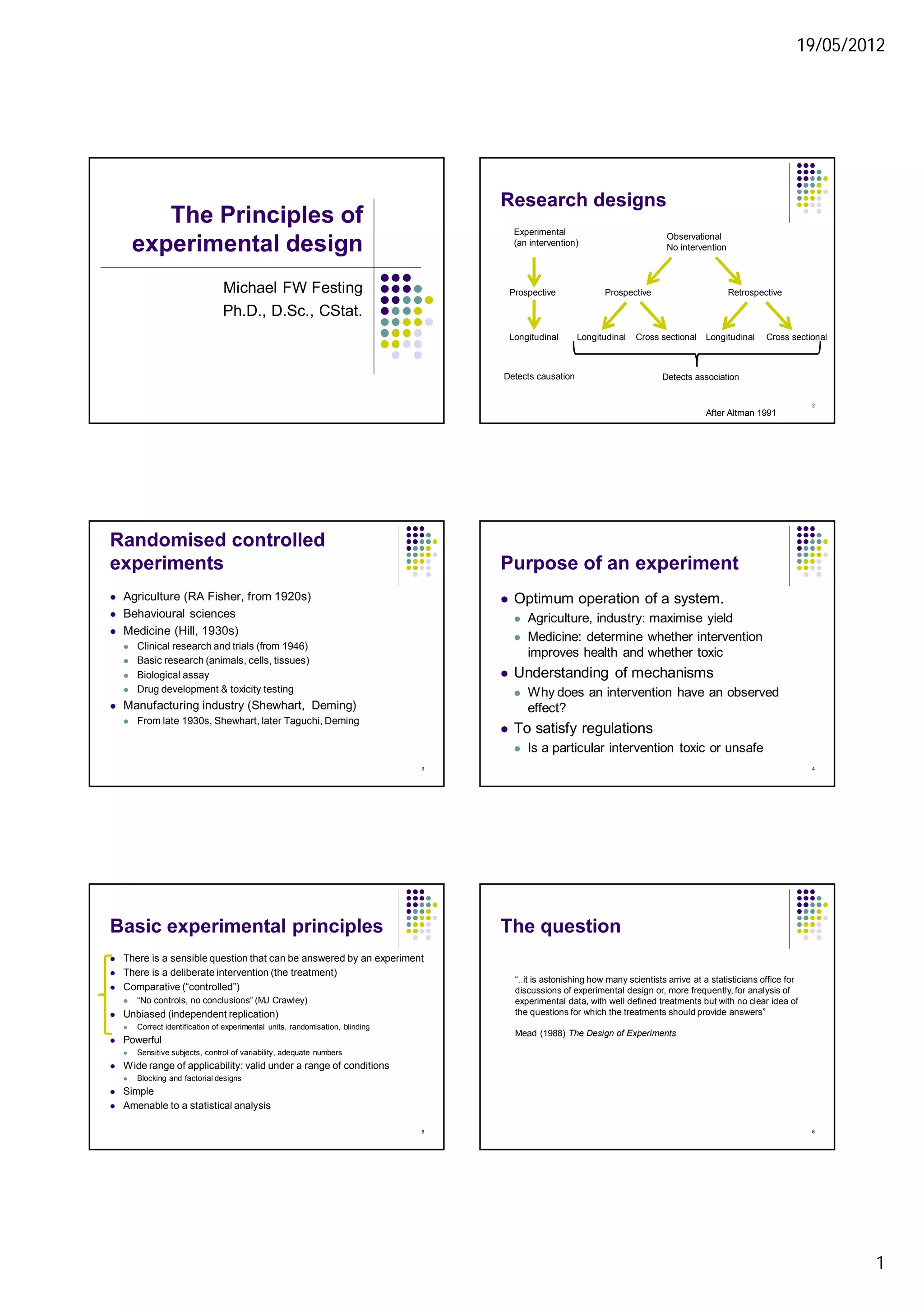

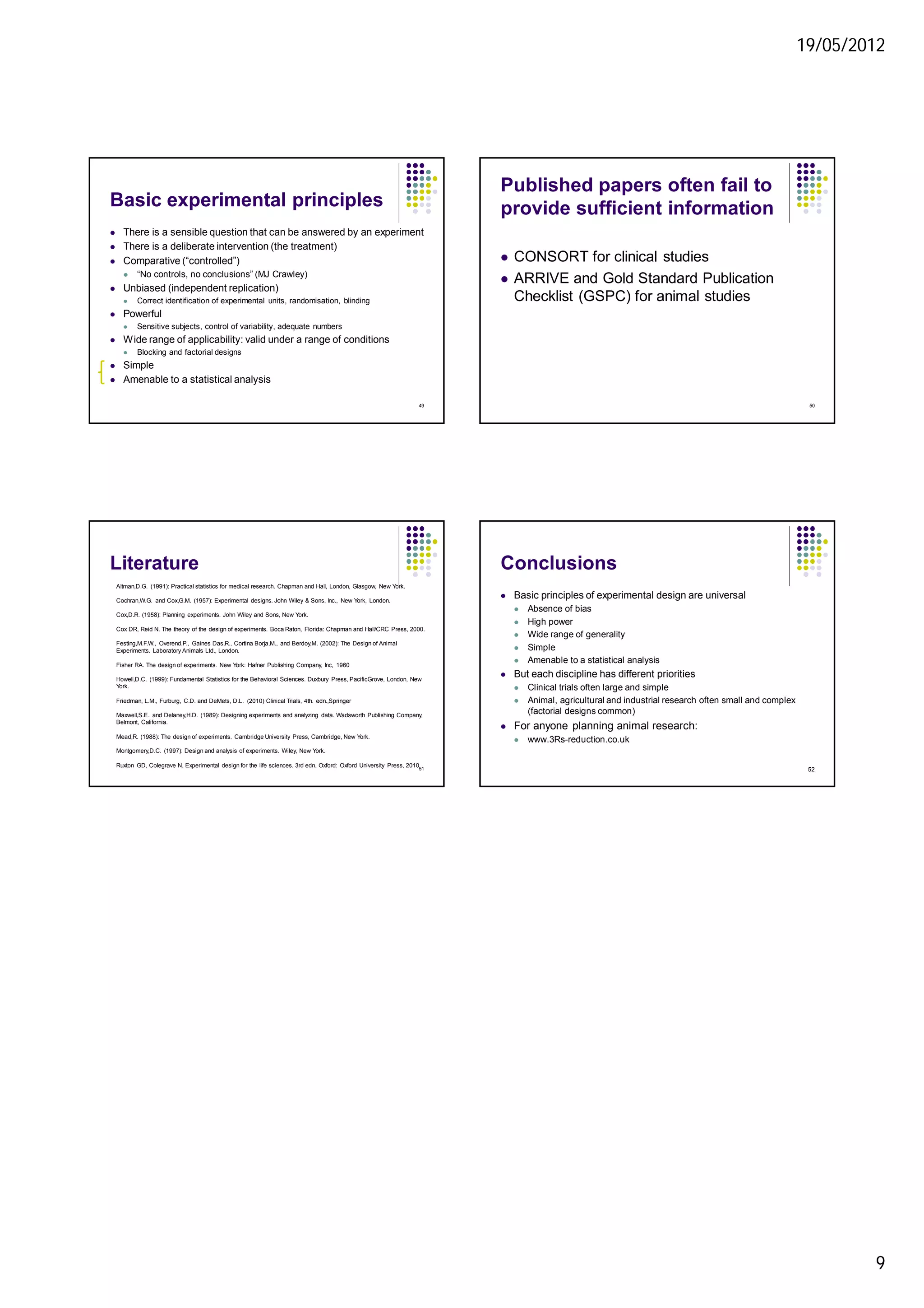

This document discusses key principles of experimental design, including:

1. Experiments should aim to answer a clear question.

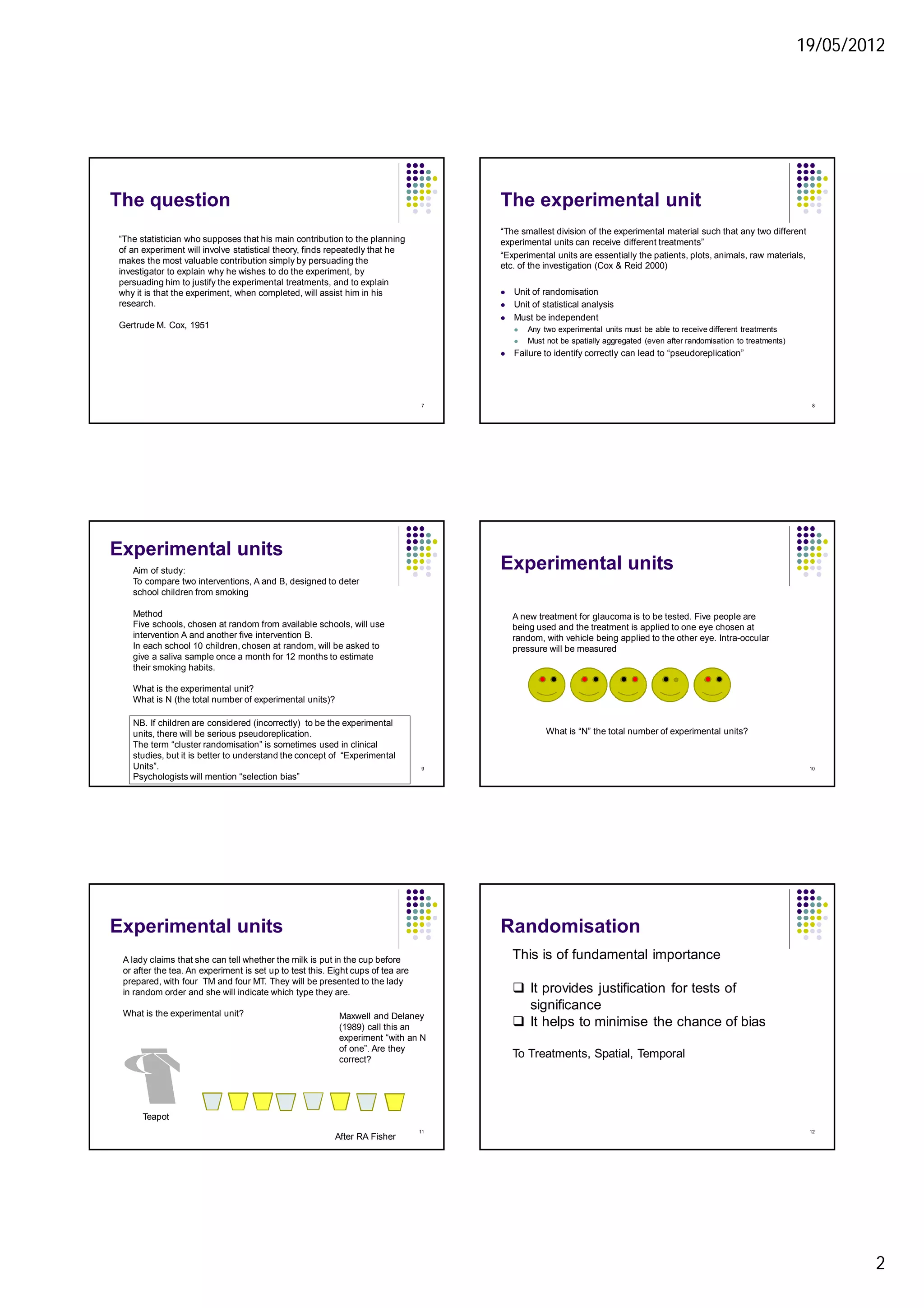

2. Randomisation and blinding are important to reduce bias. The experimental unit must also be correctly identified.

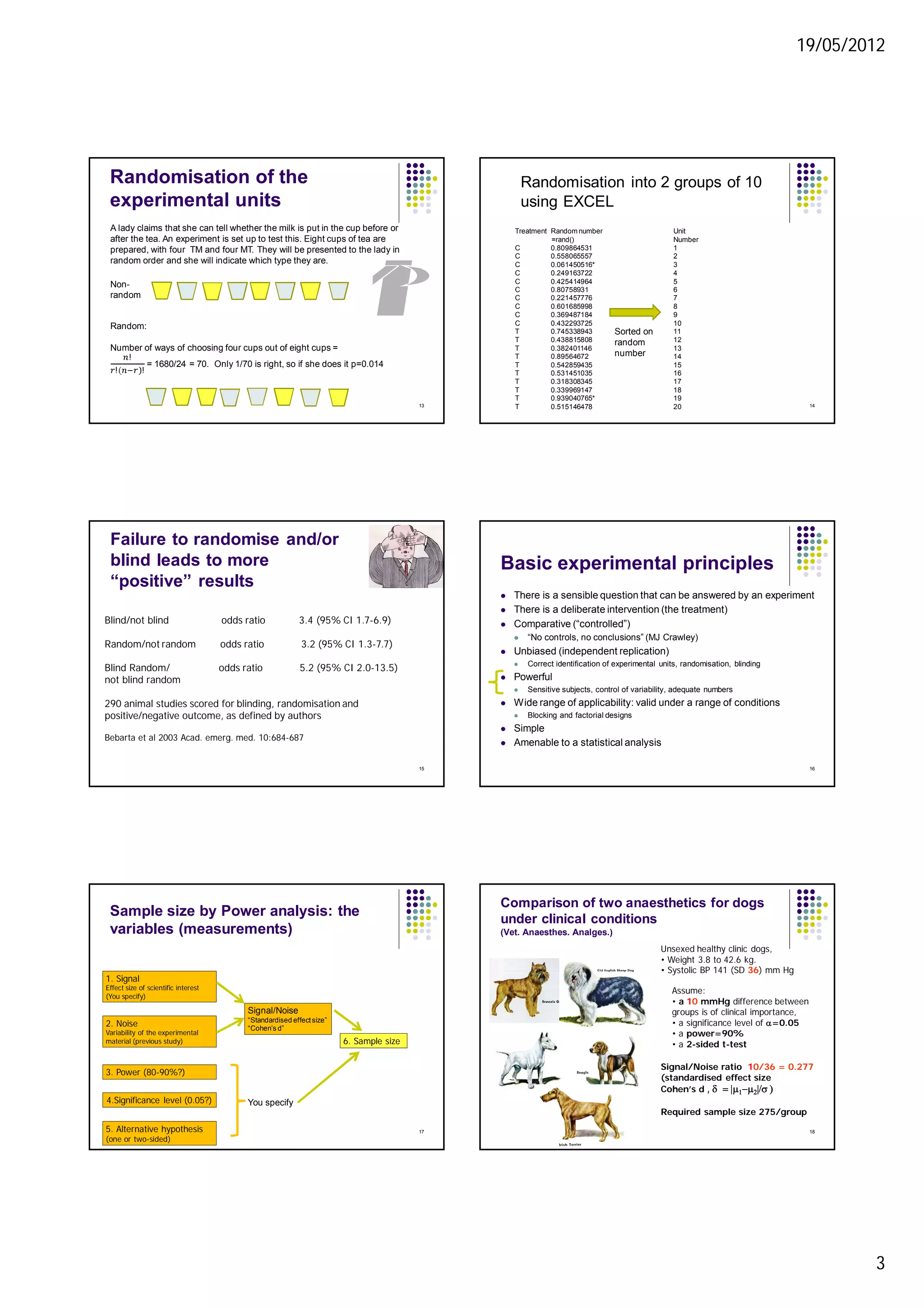

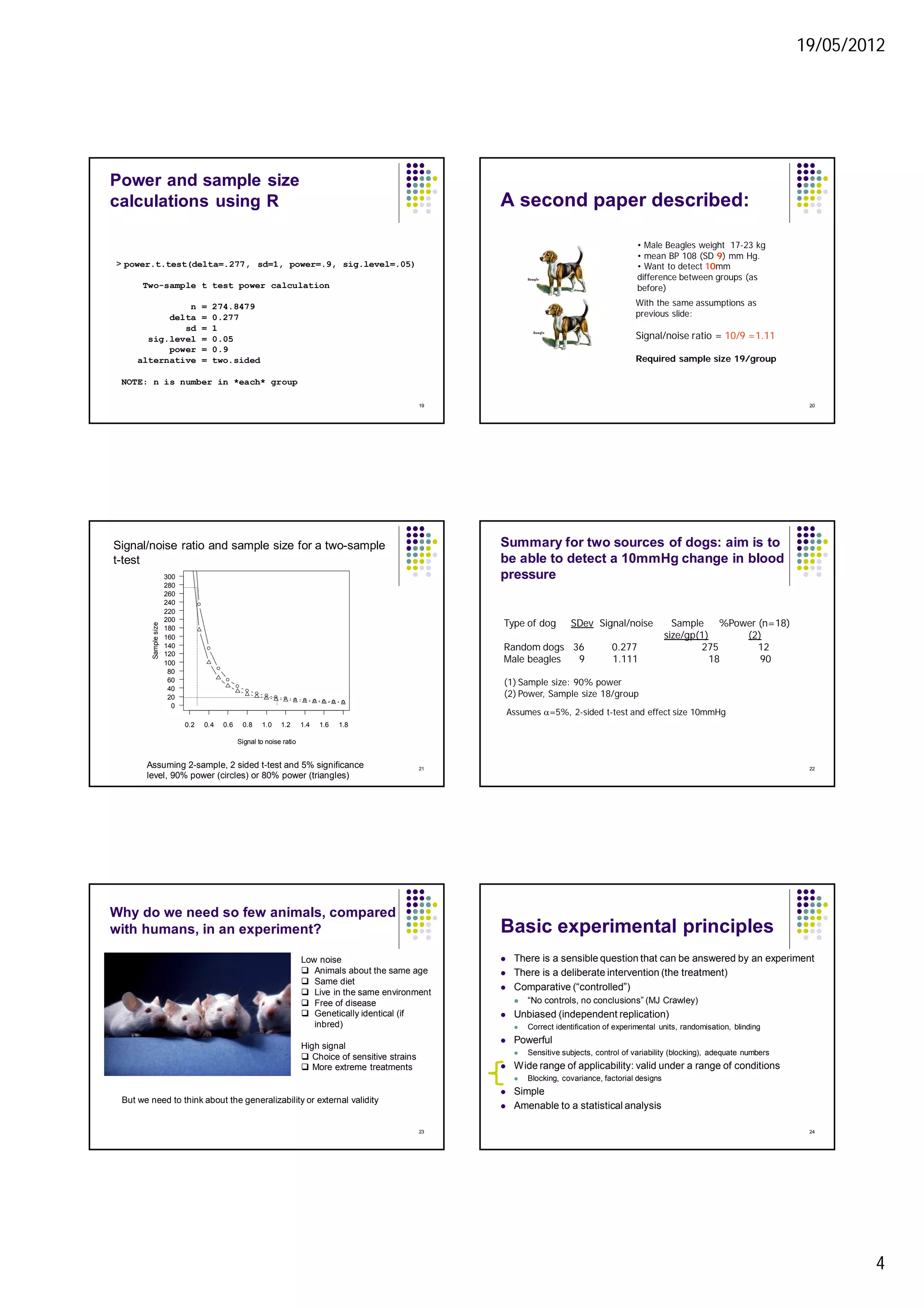

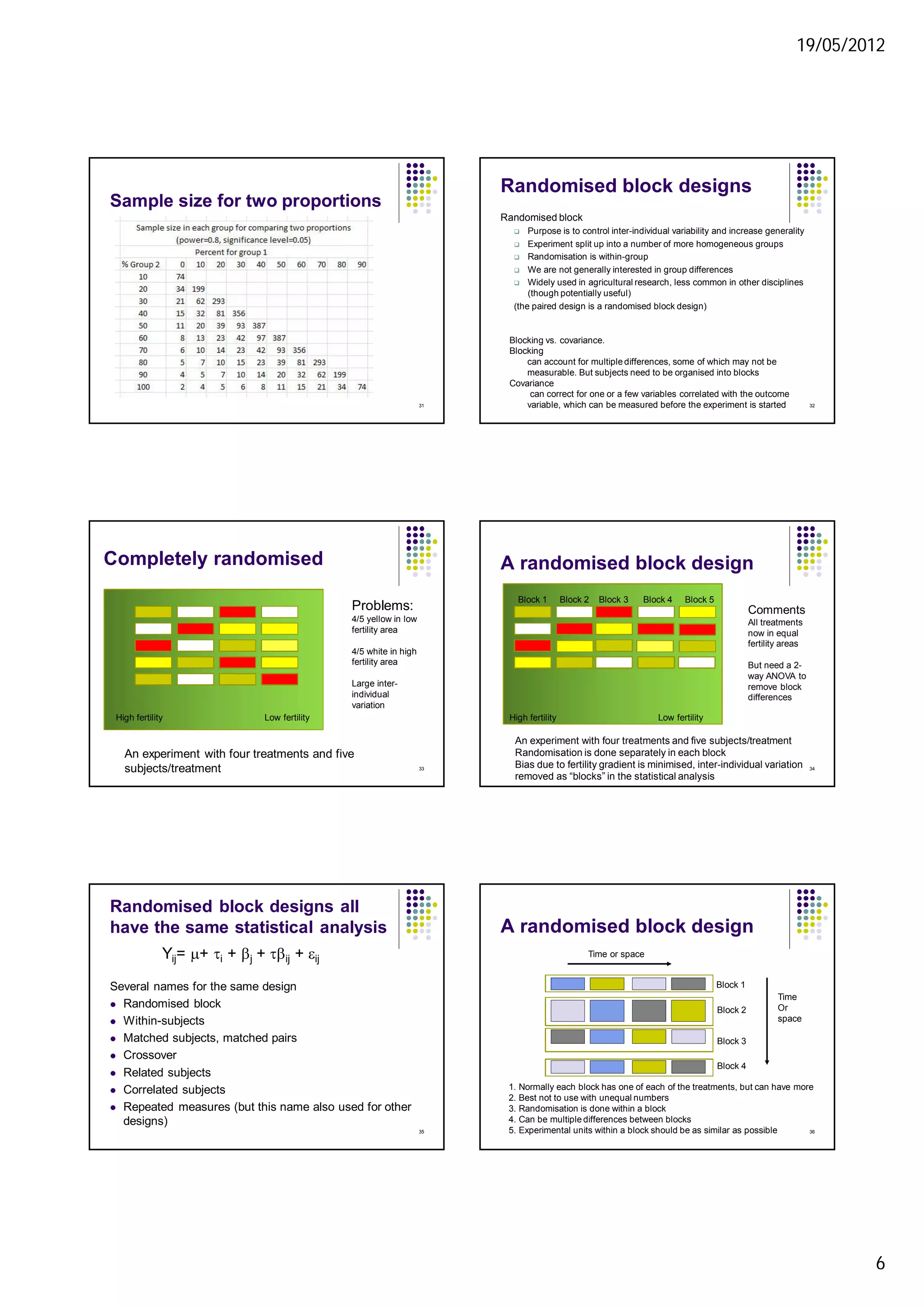

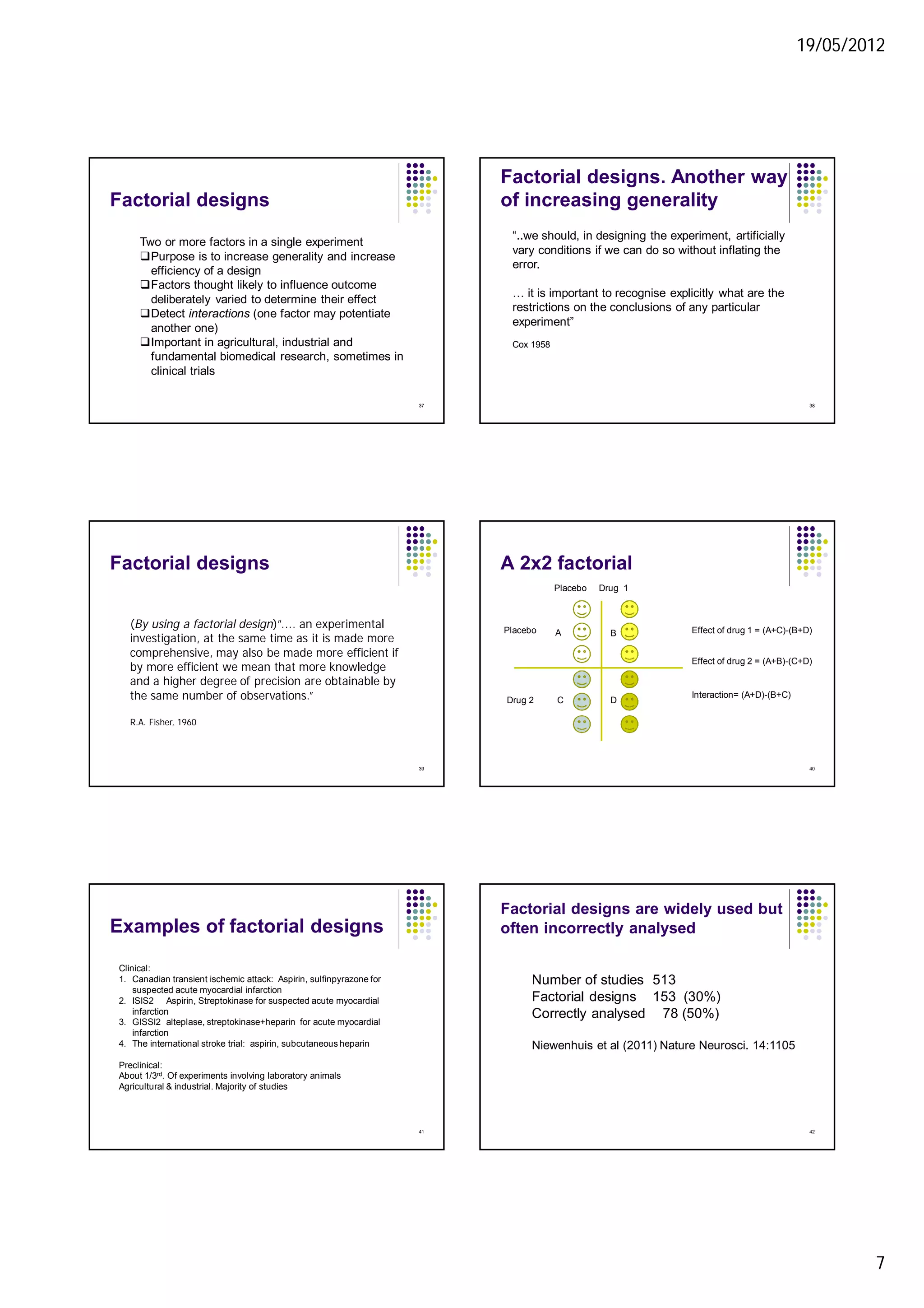

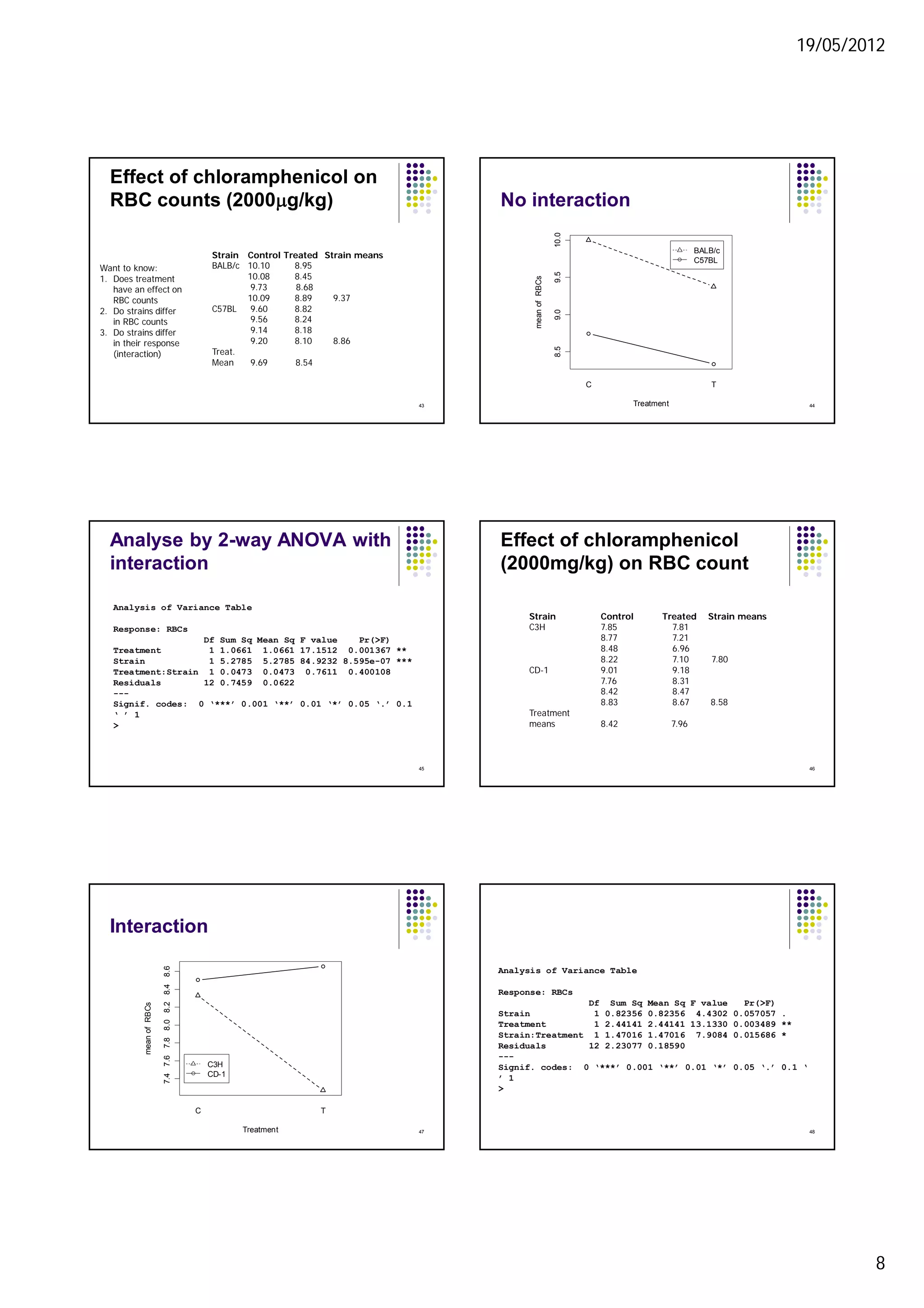

3. Power calculations are used to determine adequate sample sizes based on expected variability, effect size, and desired power. More homogeneous subjects require smaller sample sizes.

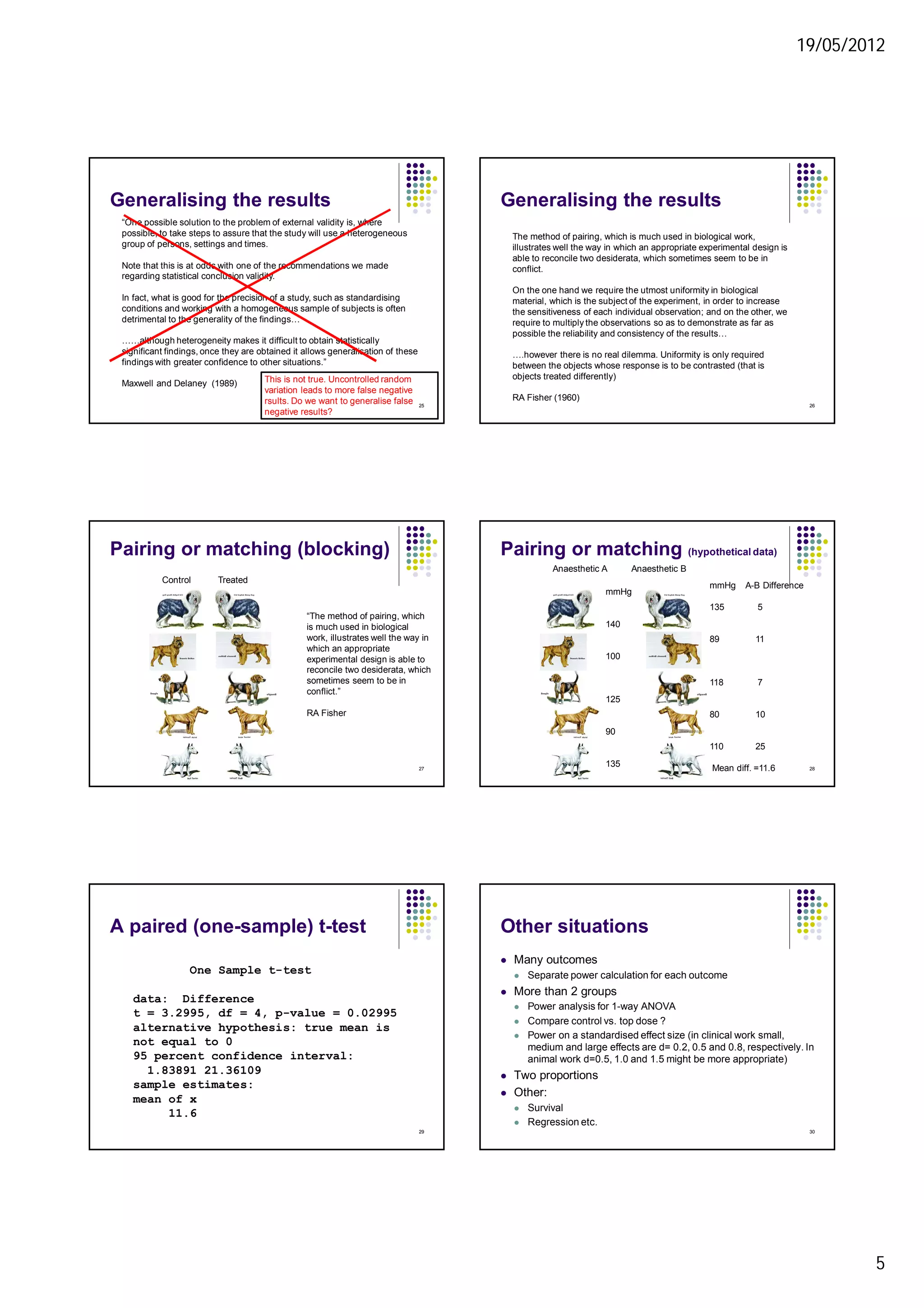

4. While randomisation increases precision, heterogeneity may allow broader generalisation of results if significant effects are found. Appropriate experimental designs like blocking can balance these considerations.