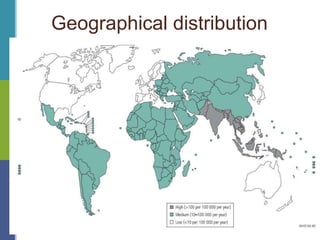

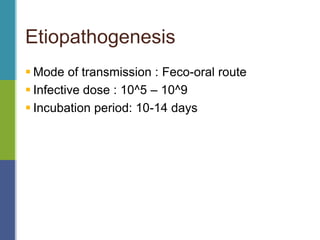

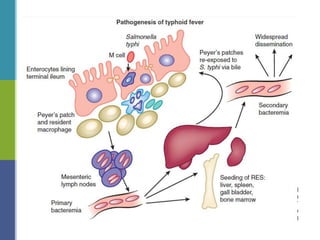

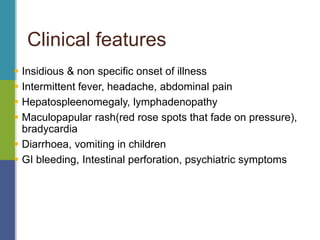

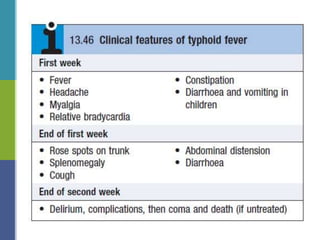

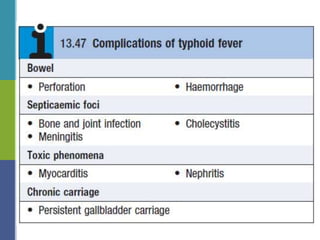

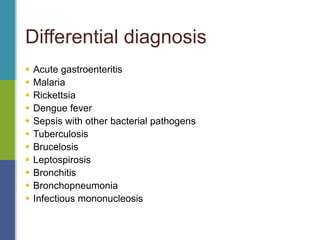

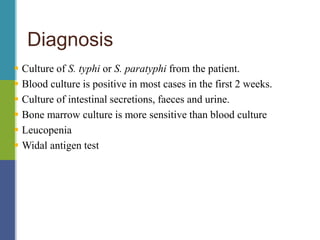

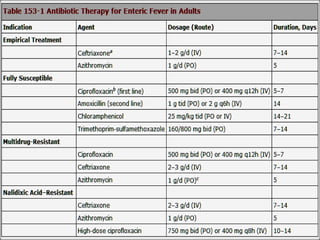

Enteric fever, caused mainly by Salmonella enterica, affects over 17 million people annually, with high prevalence in India and Africa, resulting in approximately 600,000 deaths. It presents with non-specific symptoms such as fever, headache, and abdominal pain, and can lead to severe complications if untreated. Diagnosis typically involves blood cultures, and prevention focuses on sanitation, safe drinking practices, and vaccines.