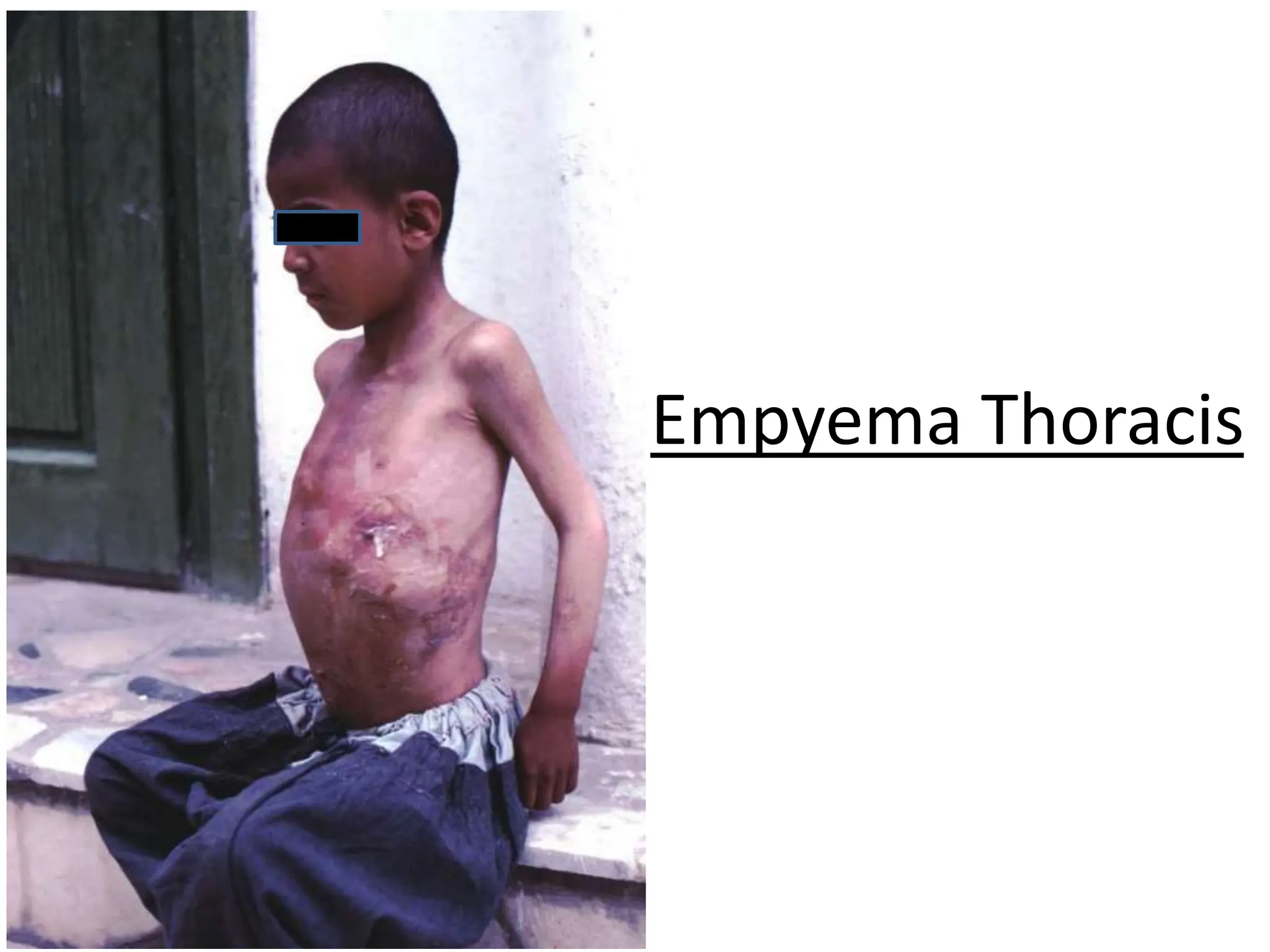

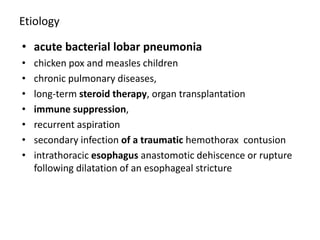

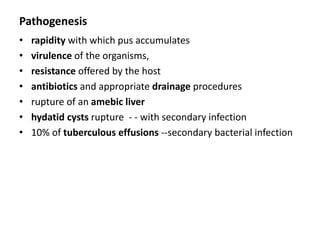

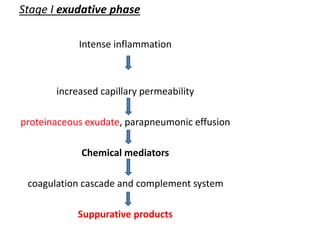

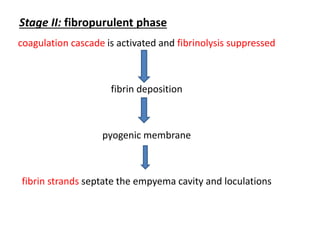

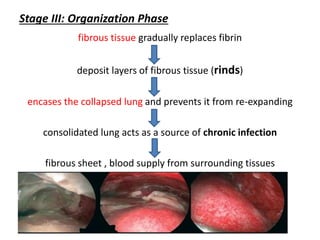

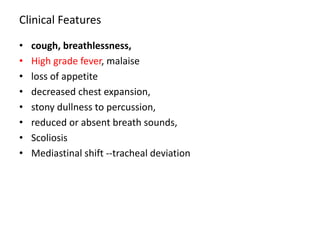

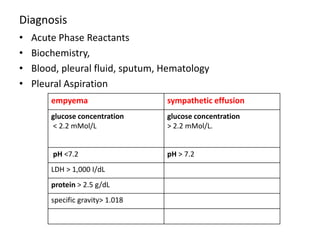

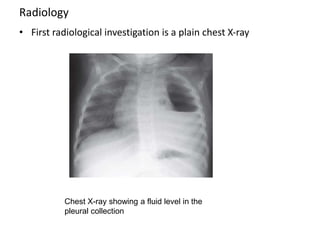

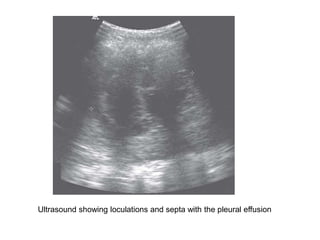

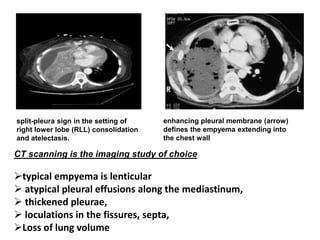

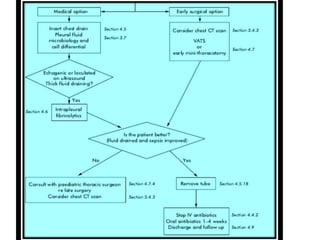

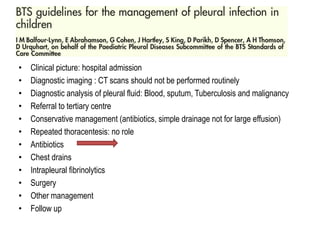

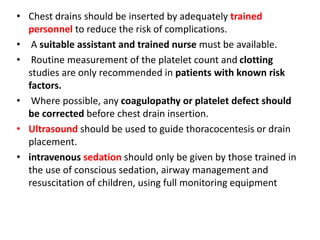

Empyema thoracis is an accumulation of pus in the pleural cavity that can develop as a complication of pneumonia. It involves three stages: exudative, fibropurulent, and organization. Clinical features include fever, cough, and chest pain. Diagnosis involves pleural fluid analysis and imaging like chest X-ray or CT scan. Treatment may include antibiotics, chest tube drainage, intrapleural fibrinolytics, and surgery like VATS. Early recognition and treatment can prevent disease progression and reduce length of hospital stay. While VATS has benefits, fibrinolytics and tube drainage are effective for select cases.

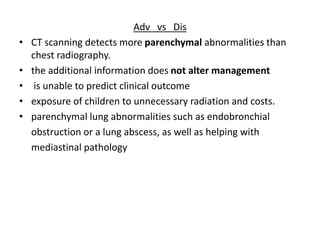

![The treatment of ET is complex. Failure to adequately evacuate

the pleural space and/or persistent signs of infection should

prompt surgical intervention.

Surgical therapy is preferred for advanced stages of ET.

Delaying definitive surgical treatment is largely responsible for

prolonging hospital course.

[Am J Med Sci 2003;326(1):9–14.]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/empyema-231213162041-ee76d4de/85/Empyema-ppt-34-320.jpg)