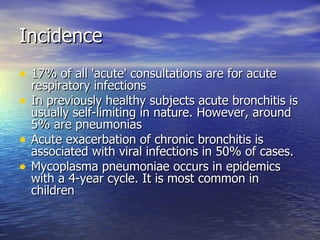

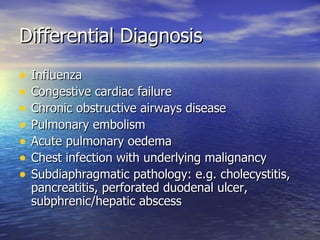

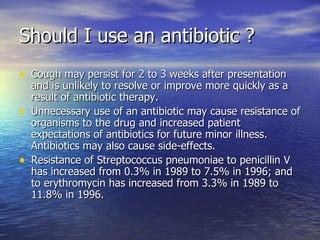

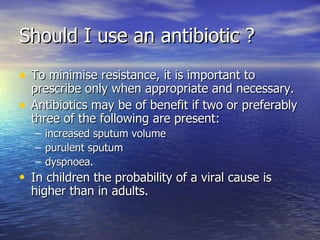

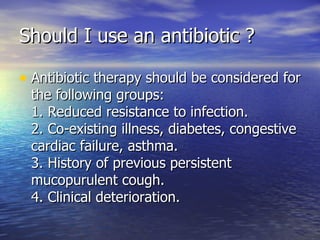

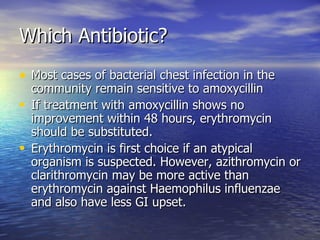

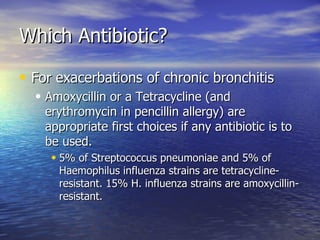

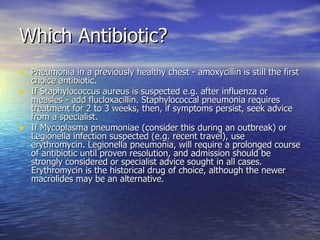

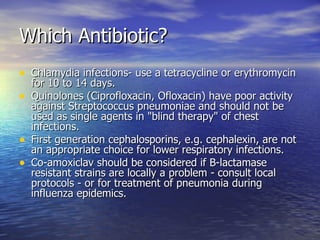

This document discusses different types of chest infections including acute bronchitis, acute exacerbation of chronic bronchitis, and community acquired pneumonia. It outlines the typical bacteria that cause each infection and symptoms. Guidelines are provided on when antibiotics are appropriate and which antibiotics to use for different situations. Amoxicillin is usually recommended initially but alternatives like erythromycin are suggested if no improvement occurs.