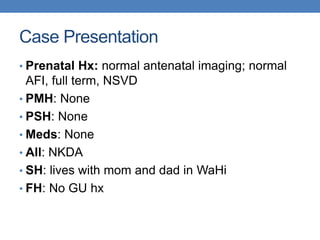

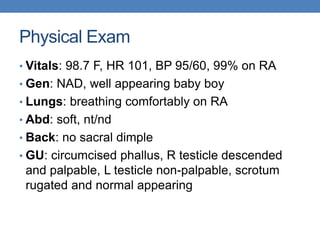

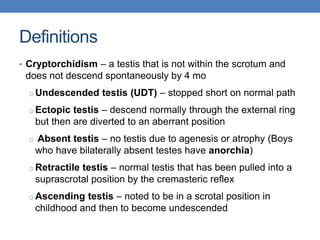

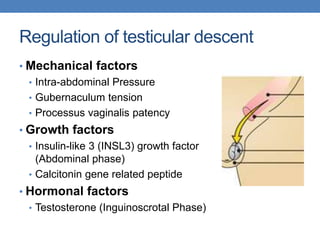

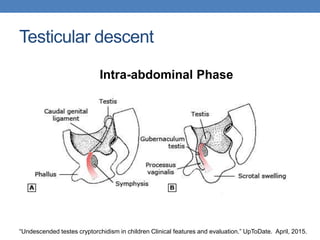

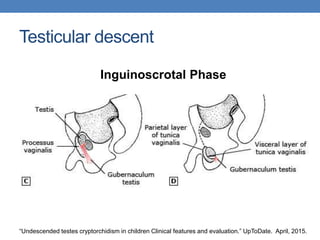

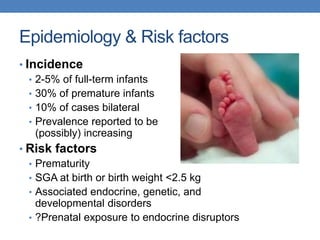

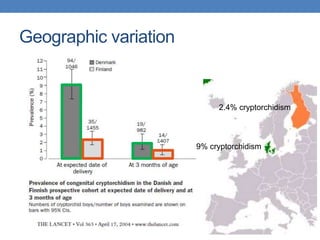

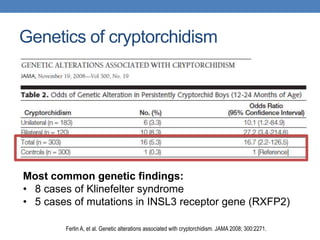

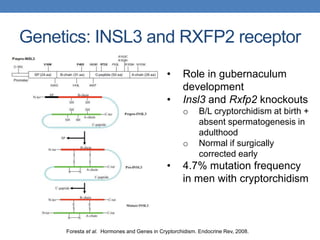

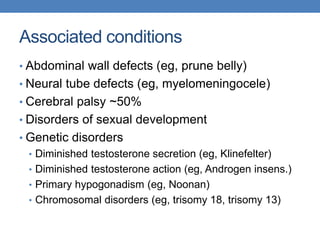

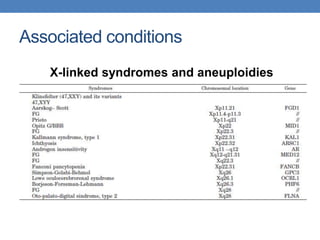

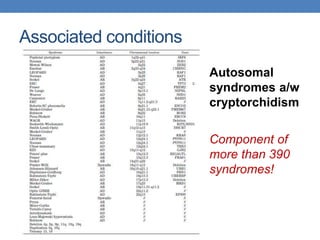

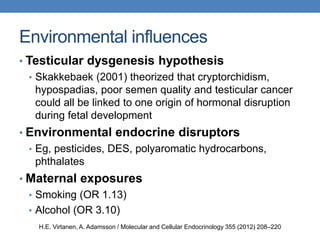

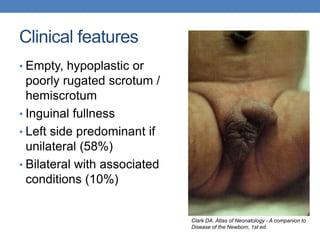

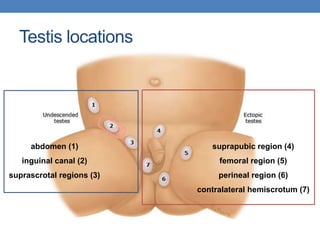

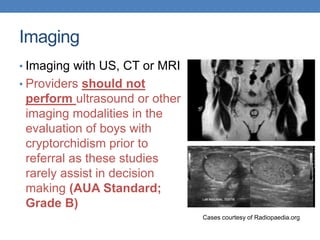

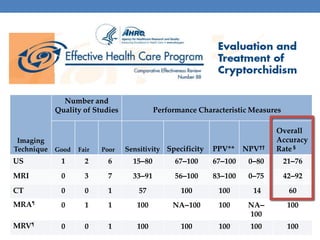

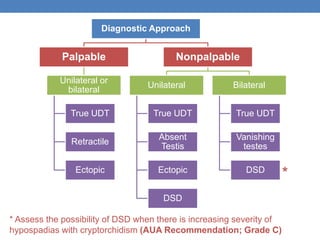

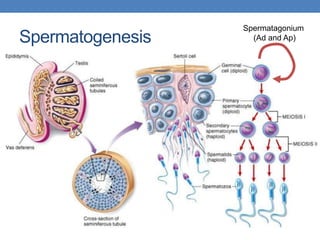

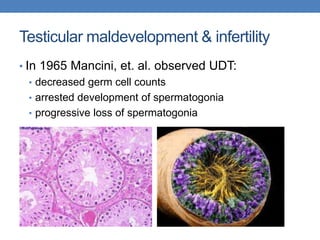

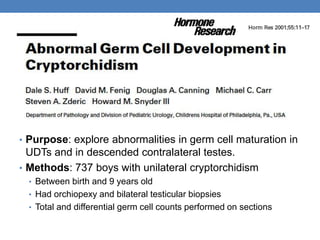

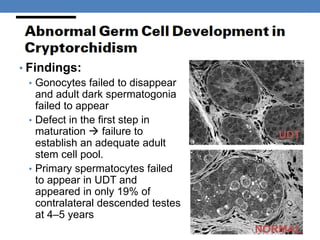

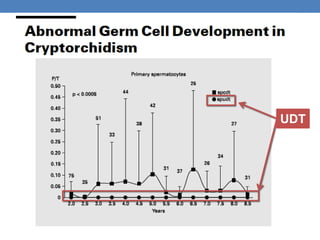

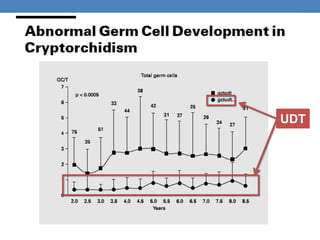

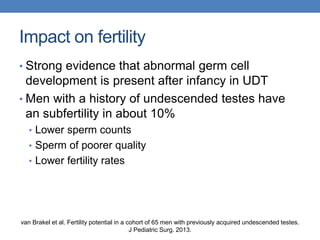

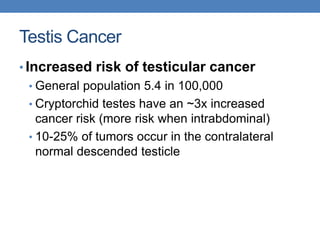

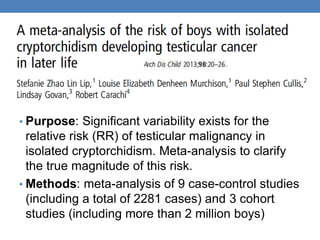

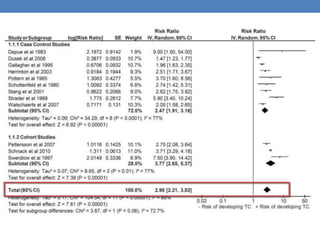

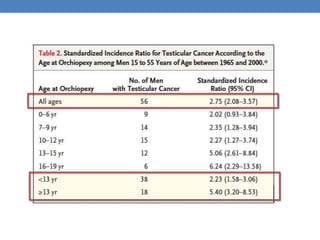

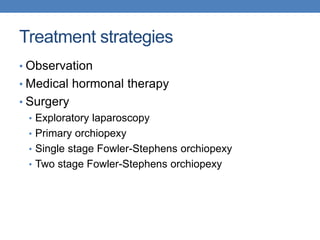

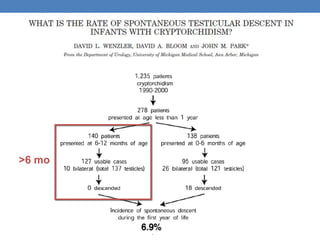

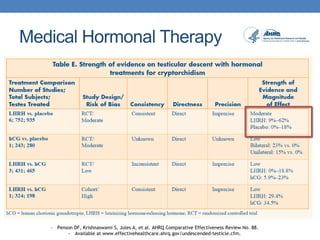

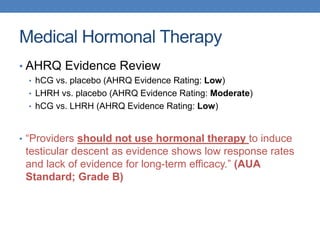

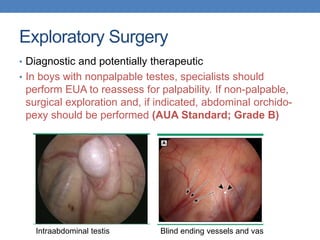

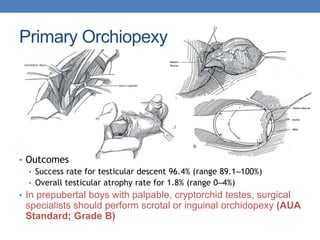

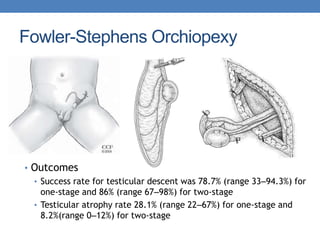

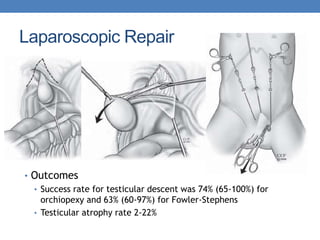

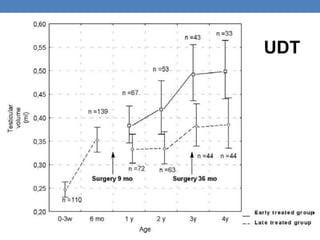

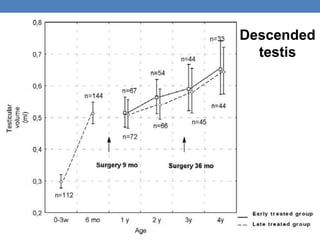

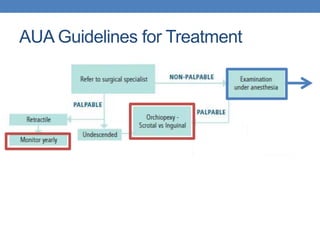

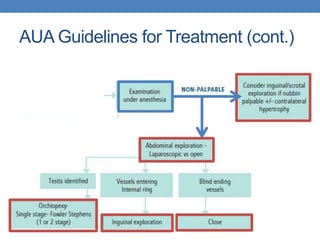

The document discusses cryptorchidism, a condition where one or both testicles are not appropriately positioned in the scrotum at birth, emphasizing its evaluation, consequences, and management strategies. It presents a case study involving a 3-month-old boy with an undescended left testicle and examines various factors including genetics, associated conditions, diagnostic approaches, and treatment options, particularly focusing on surgical interventions. Key recommendations note that orchidopexy is the most successful therapy, while hormonal therapy is discouraged due to low efficacy and highlight the need for timely intervention and proper follow-up.