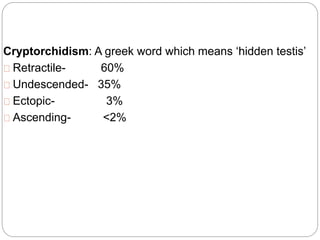

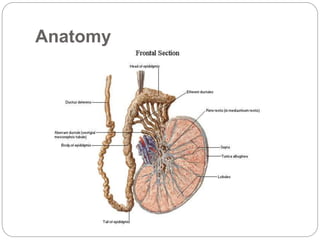

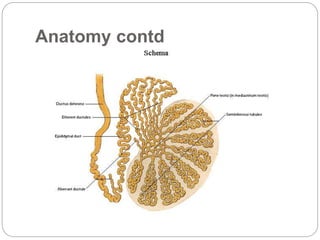

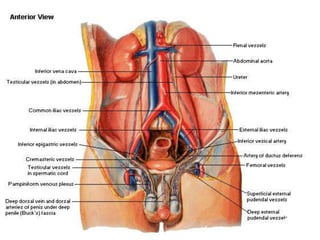

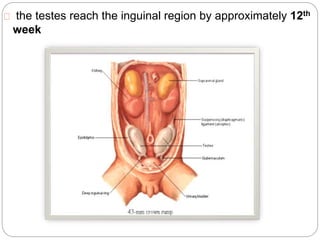

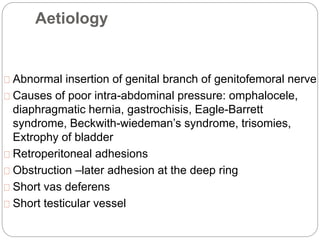

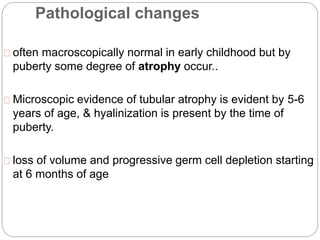

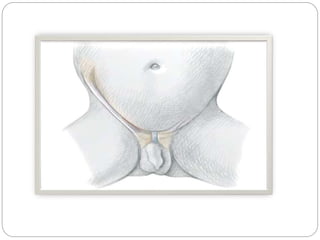

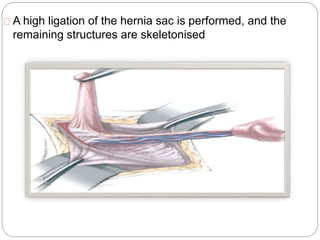

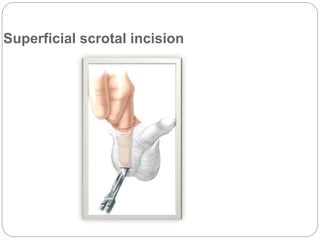

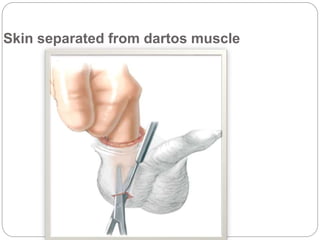

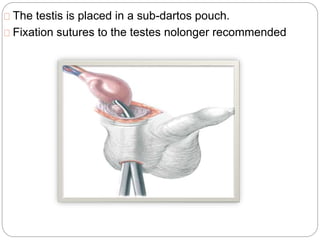

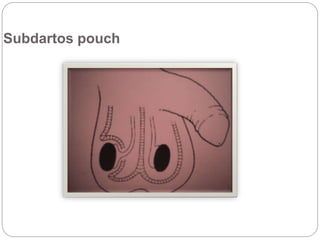

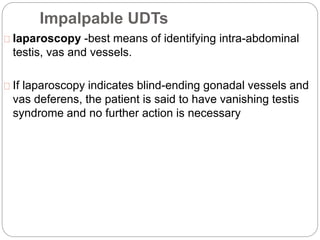

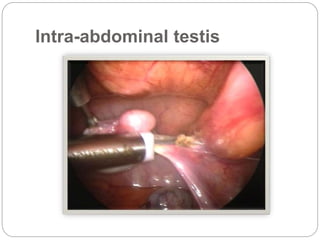

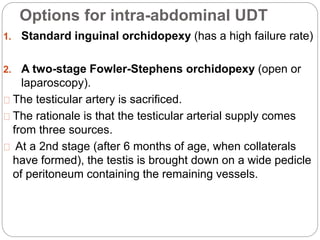

Undescended testes is one of the most common problems in pediatric surgery clinics. It occurs when one or both testes fail to descend into the scrotum. Left untreated, it can lead to testicular atrophy and infertility. The standard treatment is orchidopexy surgery to bring the testes into the scrotum. Early surgery is recommended before age 6 months to prevent damage to the testes. For intra-abdominal undescended testes, options include open orchidopexy, laparoscopic-assisted surgery, or microvascular transplantation of the testes into the scrotum. Prompt surgical treatment is aimed at reducing risks of infertility and testicular cancer.