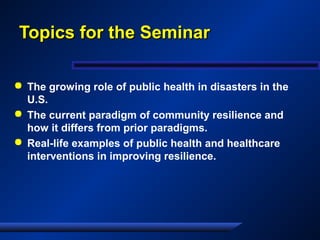

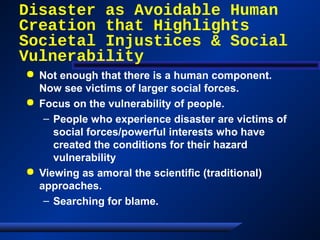

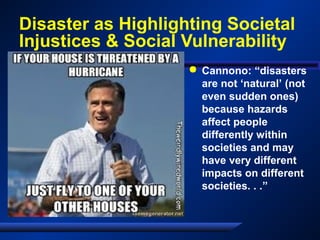

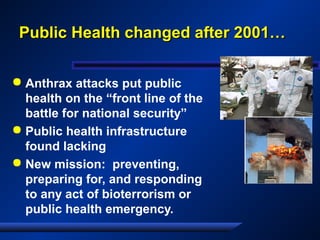

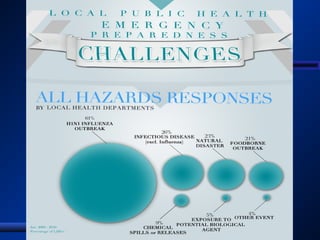

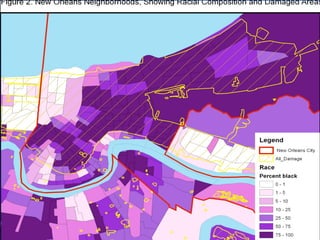

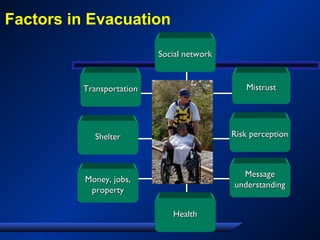

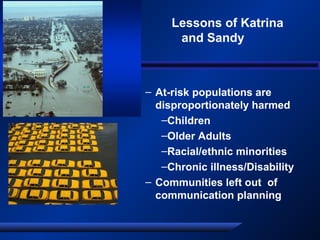

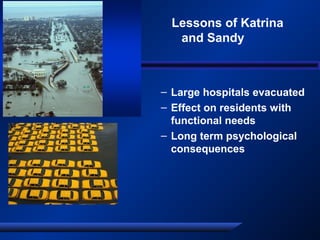

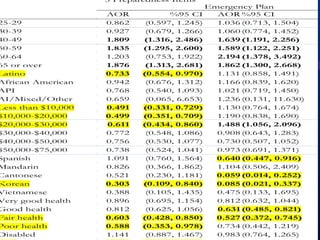

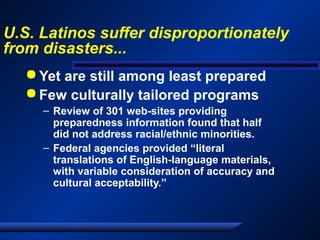

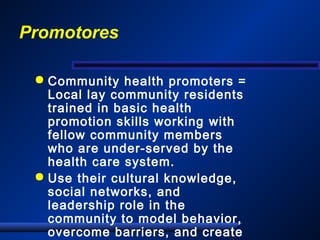

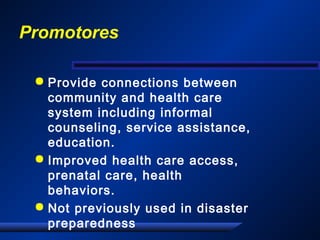

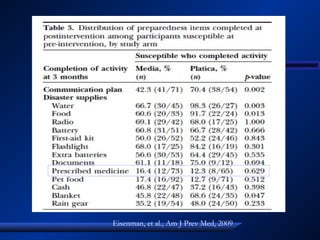

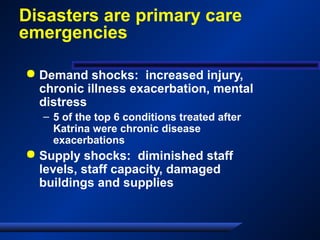

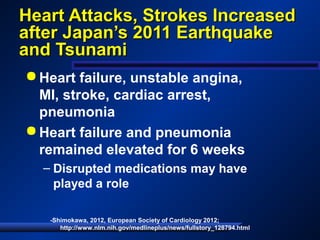

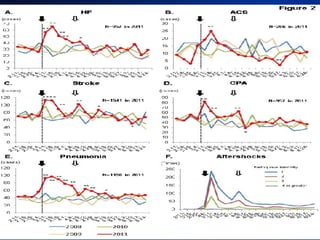

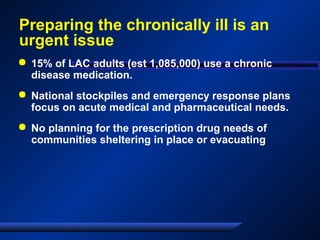

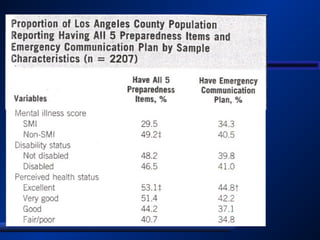

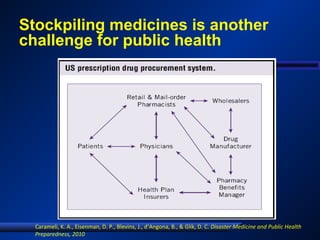

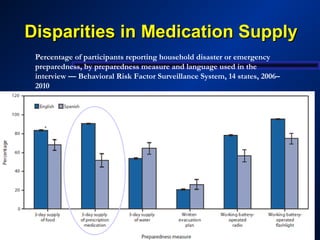

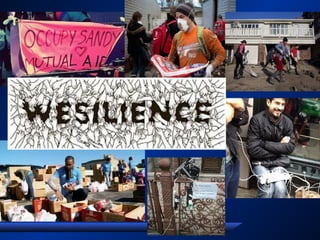

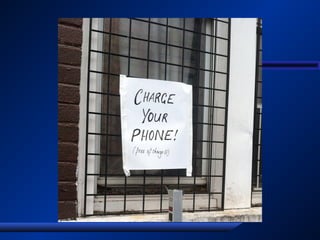

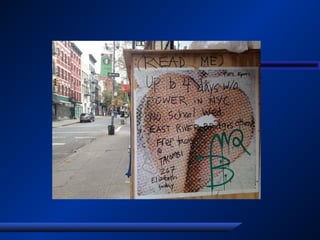

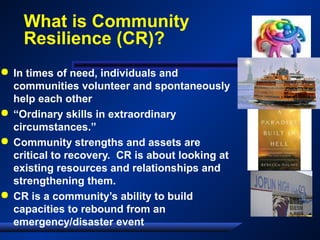

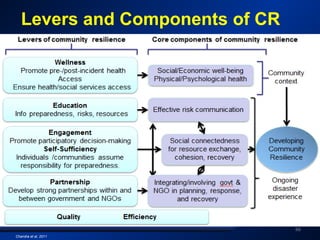

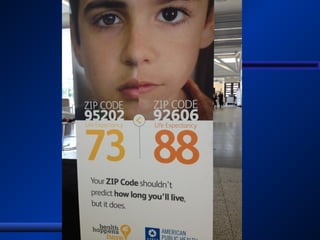

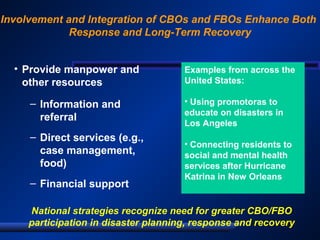

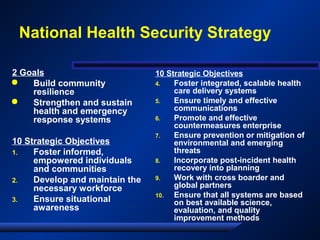

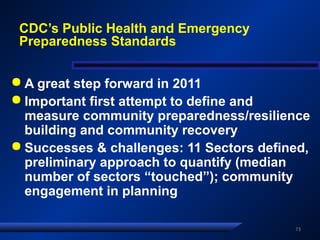

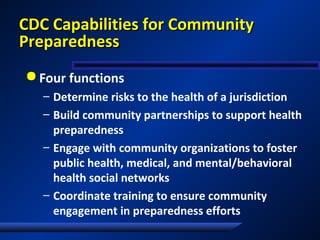

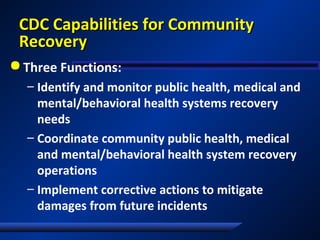

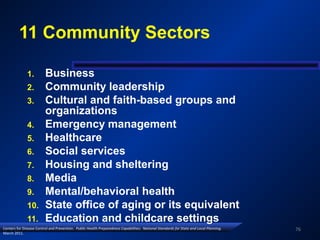

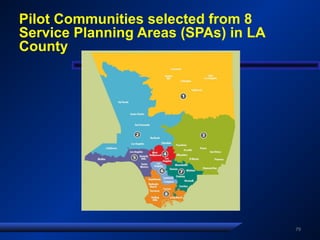

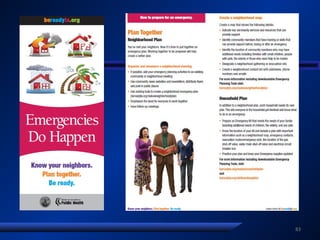

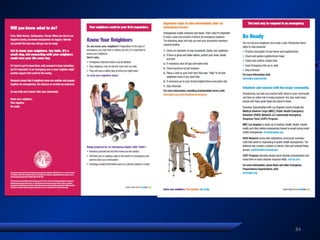

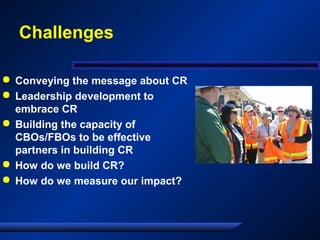

The document discusses the evolving role of public health in community disaster resilience, emphasizing the need for a paradigm shift from traditional emergency preparedness to a community-centric approach that highlights social vulnerabilities and collective action. It outlines real-life examples and strategies to enhance resilience, especially for marginalized populations disproportionately affected by disasters. Furthermore, the text advocates for integrating community resources and engagement into disaster preparedness and recovery efforts to mitigate risks and improve outcomes.