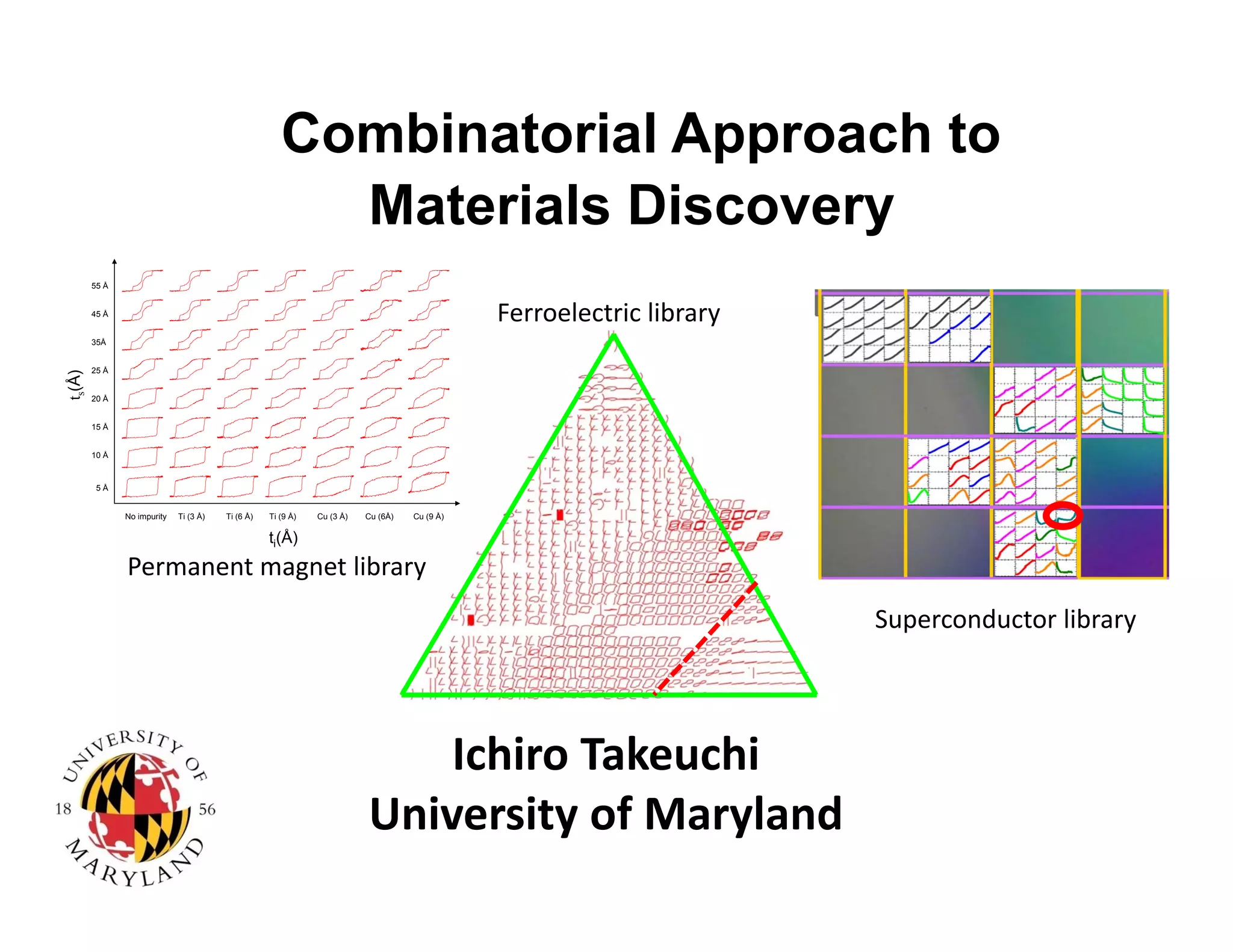

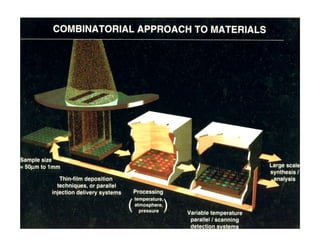

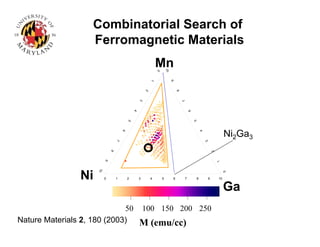

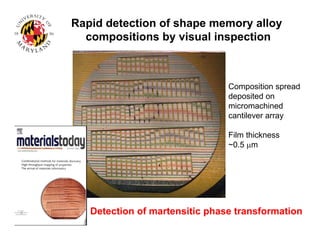

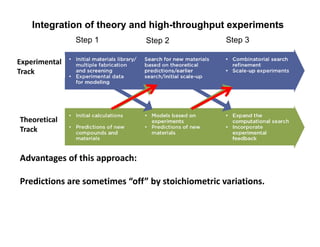

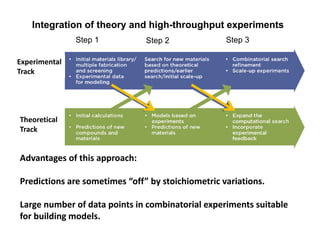

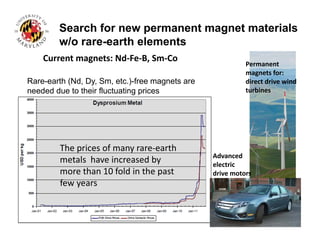

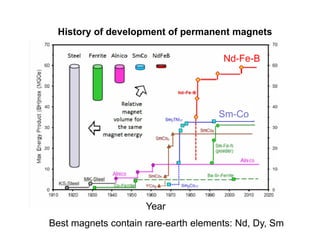

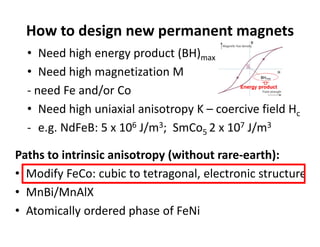

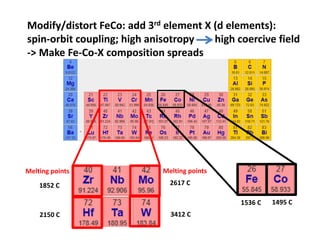

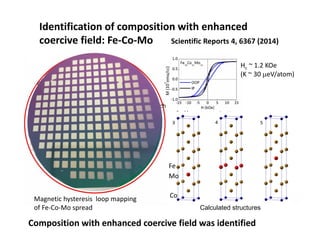

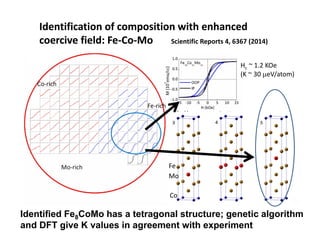

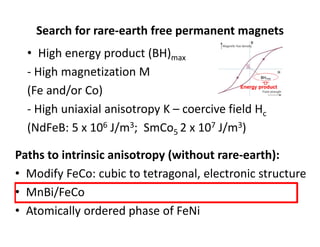

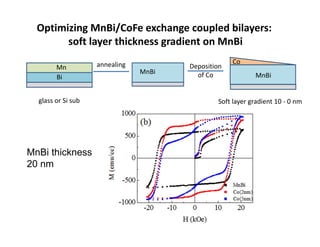

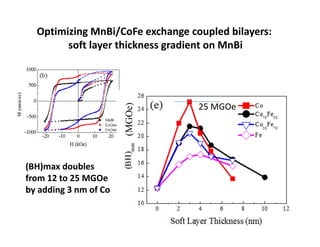

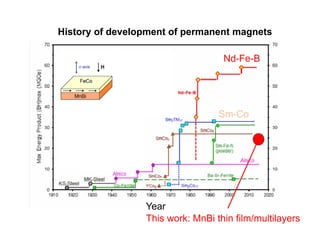

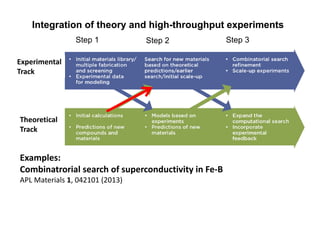

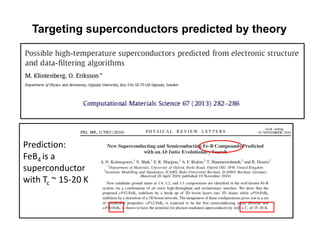

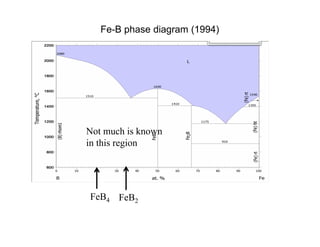

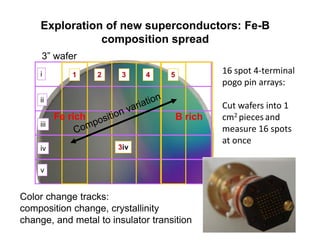

The document discusses a combinatorial approach to materials discovery, focusing on the development and characterization of various inorganic materials, including permanent magnets and superconductors. It highlights the integration of high-throughput experimental methods with theoretical models to explore large compositional phase spaces and to identify new materials with desired properties. The advancements include techniques for library fabrication, rapid characterization tools, and examples of successful material searches, particularly for rare-earth-free permanent magnets.

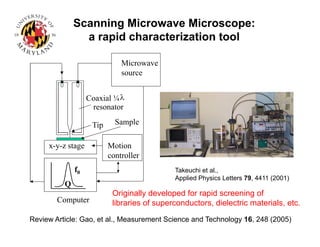

![Mode/materials

[reference]

Physical parameter/

phenomenon

Spatial

resolution

Dielectric [12-14] Complex dielectric

constant

100 nm

Metal [13] Impedance/resistivity 100 nm

Non-linear

dielectric [15,18]

Non-linear dielectric

constant

1 nm

FMR Ferromagnetic

resonance

100 nm*

STM-ESR Electron

spin resonance

Atomic

resolution

Capabilities of Multiscale Microwave Microscope

Mapping of various physical properties can be obtained

at macroscopic scale (~ 1 cm) down to the listed spatial resolution](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/takeuchiplenary2compatibilitymode-151002203614-lva1-app6892/85/Combinatorial-approach-to-materials-discovery-30-320.jpg)

![FeBx: we have found the superconductor

Susceptibility

shows diamagnetism

Bc2(T)= Bc2(0)[1-(T/Tc)2]/ [1+(T/Tc)2]

gives Bc2(0) = 2 T

-> Type II BCS superconductor

Partial R drop

~ 10 K?

Superconducting phase was detected in 2 spread wafers](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/takeuchiplenary2compatibilitymode-151002203614-lva1-app6892/85/Combinatorial-approach-to-materials-discovery-60-320.jpg)