This document provides information about the editorial board and staff for the book "Characterization of Materials". It lists the editor-in-chief, Elton N. Kaufmann, and 20 associate editors from various universities and national laboratories. It also lists the editorial staff at John Wiley & Sons, including the VP of STM Books, executive editor, editor, director of book production and manufacturing, managing editor, and assistant managing editor. The document indicates that Characterization of Materials is available online in full color on Wiley's website and that the book is a two-volume publication covering various techniques for characterizing materials.

![A key choice that must be made in the selection of a bal-

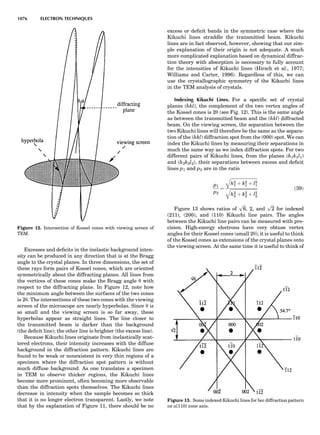

ance for the laboratory is that of the operating range. A

market survey of commercially available laboratory bal-

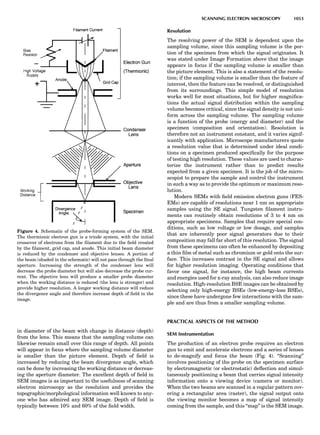

ances reveals that certain categories of balances are avail-

able. Table 1 presents common names applied to balances

operating in a variety of weight measurement capacities.

The choice of a balance or a set of balances to support a spe-

cific project is thus the responsibility of the investigator.

Electronically controlled balances usually include a

calibration routine documented in the operation manual.

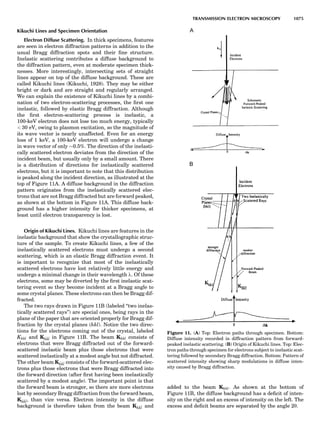

Where they differ, the routine set forth in the relevant

ASTM reference (E1270, E319, or E898) should be consid-

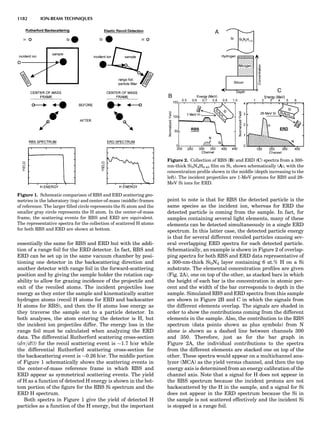

ered while the investigator identifies the control standard

for the measurement process. Another consideration is the

comparison of the operating range of the balance with the

requirements of the measurement. An improvement in lin-

earity and precision can be realized if the calibration rou-

tine is run over a range suitable for the measurement,

rather than the entire operating range. However, the inte-

gral software of the electronics may not afford the flexibil-

ity to do such a limited function calibration. Also, the

actual operation of an electronically controlled balance

involves the use of a tare setting to offset such weights

as that of the container used for a sample measurement.

The tare offset necessitates an extended range that is fre-

quently significantly larger than the range of weights to be

measured.

MASS MEASUREMENT PROCESS ASSURANCE

An instrument is characterized by its capability to repro-

ducibly deliver a result with a given readability. We often

refer to a calibrated instrument; however, in reality there

is no such thing as a calibrated balance per se. There are

weight standards that are used to calibrate a weight mea-

surement procedure, but that procedure can and should

include everything from operator behavior patterns to sys-

tematic instrumental responses. In other words, it is the

measurement process, not the balance itself that must be

calibrated. The basic maxims for evaluating and calibrat-

ing a mass measurement process are easily translated to

any quantitative measurement in the laboratory to which

some standards should be attached for purposes of report-

ing, quality assurance, and reproducibility. While certain

industrial, government, and even university programs

have established measurement assurance programs [e.g.,

as required for International Standards Organization

(ISO) 9000/9001 certification], the application of estab-

lished standards to research laboratories is not always

well defined. In general, it is the investigator who bears

the responsibility for applying standards when making

measurements and reporting results. Where no quality

assurance programs are mandated, some laboratories

may wish to institute a voluntary accreditation program.

NIST operates the National Voluntary Laboratory Accred-

itation Program [NVLAP, telephone number (301) 975-

4042] to assist such laboratories in achieving self-imposed

accreditation (Harris, 1993).

The ISO Guide on the Expression of Uncertainty

in Measurements (1992) identified and recommended a

standardized approach for expressing the uncertainty of

results. The standard was adopted by NIST and is pub-

lished in NIST Technical Note 1297 (1994). The NIST pub-

lication simplifies the technical aspects of the standard. It

establishes two categories of uncertainty, type A and type

B. Type A uncertainty contains factors associated with

random variability, and is identified solely by statistical

analysis of measurement data. Type B uncertainty con-

sists of all other sources of variability; scientific judgment

alone quantifies this uncertainty type (Clark, 1994). The

process uncertainty under the ISO recommendation is

defined as the square root of the sum of the squares of

the standard deviations due to all contributing factors.

At a minimum, the process variation uncertainty should

consist of the standard deviations of the mass standards

used (s), the standard deviations of the measurement pro-

cess (sP), and the estimated standard deviations due to

Type B uncertainty (uB). Then, the overall process uncer-

tainty (combined standard uncertainty) is uc ¼ [(s)2

þ

(sP)2

þ (uB)2

]1/2

(Everhart, 1995). This combined uncer-

tainty value is multiplied by the coverage factor (usually

2) to report the expanded uncertainty (U) to the 95% (2-sig-

ma) confidence level. NIST adopted the 2-sigma level for

stating uncertainties in January 1994; uncertainty state-

ments from NIST prior to this date were based on the 3-sig-

ma (99%) confidence level. More detailed guidelines for the

computation and expression of uncertainty, including a

discussion of scatter analysis and error propagation, is

provided in NIST Technical Note 1297 (1994). This docu-

ment has been adopted by the CIPM, and it is available

online (see Internet Resources).

J. Everhart (JTI Systems, Inc.) has proposed a process

measurement assurance program that affords a powerful,

systematic tool for accumulating meaningful data and

insight on the uncertainties associated with a measure-

ment procedure, and further helps to improve measure-

ment procedures and data quality by integrating a

calibration program with day-to-day measurements

(Everhart, 1988). An added advantage of adopting such

an approach is that procedural errors, instrument drift

or malfunction, or other quality-reducing factors are

more likely to be caught quickly.

The essential points of Everhart’s program are sum-

marized here.

1. Initial measurements are made by metrology specia-

lists or experts in the measurement using a control

standard to establish reference confidence limits.

Table 1. Typical Types of Balance Available, by Capacity

and Divisions

Name Capacity (range) Divisions Displayed

Ultramicrobalance 2 g 0.1 mg

Microbalance 3–20 g 1 mg

Semimicrobalance 30–200 g 10 mg

Macroanalytical 50–400 g 0.1 mg

balance

Precision balance 100 g–30 kg 0.1 mg–1 g

Industrial balance 30–6000 kg 1 g–0.1 kg

28 COMMON CONCEPTS](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/characterizationofmaterials-eltonn-kaufmann-130214165548-phpapp02-150817084749-lva1-app6891/85/Characterizationofmaterials-eltonn-kaufmann-130214165548-phpapp02-48-320.jpg)

![highest temperature depends on the thermal stability of

the gas or the construction material.

Electrical-Resistance Thermometers

A resistance thermometer is dependent upon the electrical

resistance of a conducting metal changing with the tem-

perature. In order to minimize the size of the equipment,

the resistance of the wire or film should be relatively

high so that the resistance can easily be measured. The

change in resistance with temperature should also be

large. The most common material used is a platinum

wire-wound element with a resistance of $100 at 08C.

Calibration standards are essential (see the previous dis-

cussion on the International Temperature Standards).

Commercial manufacturers will provide such instruments

together with calibration details. Thin-film platinum ele-

ments may provide an alternative design feature and are

priced competitively with the more common wire-wound

elements. Nickel and copper resistance elements are also

commercially available.

Thermocouple Thermometers

A thermocouple is an assembly of two wires of unlike

metals joined at one end where the temperature is to be

measured. If the other end of one of the thermocouple

wires leads to a second, similar junction that is kept at a

constant reference temperature, then a temperature-

dependent voltage develops called the Seebeck voltage

(see, e.g., McGee, 1988). The constant-temperature junc-

tion is often kept at 08C and is referred to as the cold

junction. Tables are available of the EMF generated ver-

sus temperature when one thermocouple is kept as a cold

junction at 08C for specified metal/metal thermocouple

junctions. These scales may show a nonlinear variation

with temperature, so it is essential that calibration be car-

ried out using phase transitions (i.e., melting points or

solid-solid transitions). Typical thermocouple systems are

summarized in Table 1.

Thermistors and Semiconductor-Based

Thermometers

There are various types of semiconductor-based thermo-

meters. Some semiconductors used for temperature mea-

surements are called thermistors or resistive temperature

detectors (RTDs). Materials can be classified as electrical

conductors, semiconductors, or insulators depending on

their electrical conductivity. Semiconductors have $10 to

106

-cm resistivity. The resistivity changes with tempera-

ture, and the logarithm of the resistance plotted against

reciprocal of the absolute temperature is often linear.

The actual value for the thermistor can be fixed by deliber-

ately introducing impurities. Typical materials used are

oxides of nickel, manganese, copper, titanium, and other

metals that are sintered at high temperatures. Most ther-

mistors have a negative temperature coefficient, but some

are available with a positive temperature coefficient. A

typical thermistor with a resistance of 1200 at 408C

will have a 120- resistance at 1108C. This represents a

decrease in resistance by a factor of about 2 for every

208C increase in temperature, which makes it very useful

for measuring very small temperature spans. Thermistors

are available in a wide variety of styles, such as small

beads, discs, washers, or rods, and may be encased in glass

or plastic or used bare as required by their intended

application. Typical temperature ranges are from À308 to

1208C, with generally a much greater sensitivity than for

thermocouples. The germanium diode is an important

thermistor due to its responsivity range—germanium

has a well-characterized response from 0.058 to 1008

Kelvin, making it well-suited to extremely low-tempera-

ture measurement applications. Germanium diodes are

also employed in emissivity measurements (see the next

section) due to their extremely fast response time—nano-

second time resolution has been reported (Xu et al., 1996).

Ruthenium oxide RTDs are also suitable for extremely

low-temperature measurement and are found in many

cryostat applications.

Radiation Thermometers

Radiation incident on matter must be reflected, trans-

mitted, or absorbed to comply with the First Law of Ther-

modynamics. Thus the reflectance, r, the transmittance, t,

and the absorbance, a, sum to unity (the reflectance [trans-

mittance, absorbance] is defined as the ratio of the

reflected [transmitted, absorbed] intensity to the incident

intensity). This forms the basis of Kirchoff’s law of optics.

Kirchoff recognized that if an object were a perfect absor-

ber, then in order to conserve energy, the object must also

be a perfect emitter. Such a perfect absorber/emitter is

called a ‘‘black body.’’ Kirchoff further recognized that

the absorbance of a black body must equal its emittance,

and that a black body would be thus characterized by a cer-

tain brightness that depends upon its temperature (Wolfe,

1998). Max Planck identified the quantized nature of the

black body’s emittance as a function of frequency by treat-

ing the emitted radiation as though it were the result of a

linear field of oscillators with quantized energy states.

Planck’s famous black-body law relates the radiant

Table 1. Some Typical Thermocouple Systemsa

System Use

Iron-Constantan Used in dry reducing atmospheres up

to 4008C

General temperature scale: 08 to 7508C

Copper-Constantan Used in slightly oxidizing or reducing

atmospheres

For low-temperature work: À2008 to 508C

Chromel-Alumel Used only in oxidizing atmospheres

Temperature range: 08 to 12508C

Chromel-Constantan Not to be used in atmospheres that are

strongly reducing atmospheres or

contain sulfur compounds

Temperature range: À2008 to 9008C

Platinum-Rhodium Can be used as components for

(or suitable thermocouples operating

alloys) up to 17008C

a

Operating conditions and calibration details should always be sought

from instrument manufactures.

36 COMMON CONCEPTS](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/characterizationofmaterials-eltonn-kaufmann-130214165548-phpapp02-150817084749-lva1-app6891/85/Characterizationofmaterials-eltonn-kaufmann-130214165548-phpapp02-56-320.jpg)

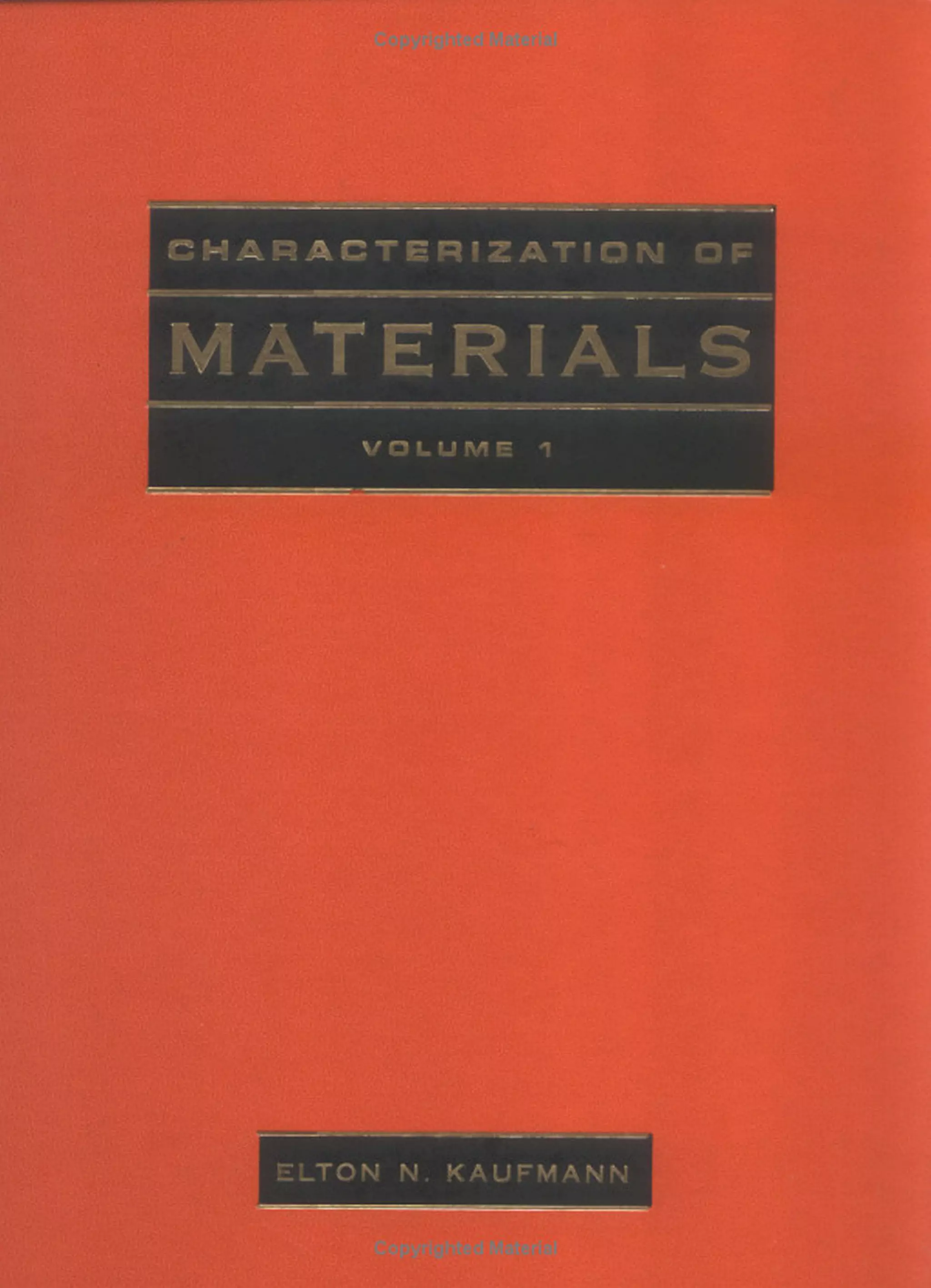

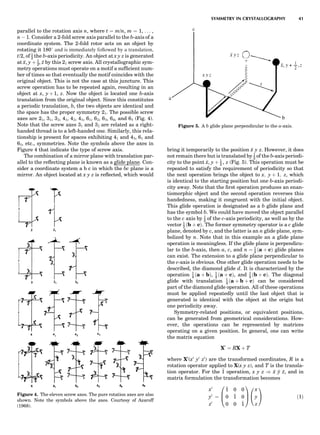

![CRYSTAL SYSTEMS

The presence of a symmetry operator imparts a distinct

appearance to a crystal. A 3-fold axis means that crystal

faces around the axis must be identical every 1208. A 4-

fold axis must show a 908 relationship among faces. On

the basis of the appearance of crystals due to symmetry,

classical crystallographers could divide them into seven

groups as shown in Table 1. The symbol 6¼ should be

read as ‘‘not necessarily equal.’’ The relationship among

the metric parameters is determined by the presence of

the symmetry operators among the atoms of the unit

cell, but the metric parameters do not determine the crys-

tal system. Thus, one could have a metrically cubic cell,

but if only 1-fold axes are present among the atoms of

the unit cell, then the crystal system is triclinic. This is

the case for hexamethylbenzene, but, admittedly, this is

a rare occurrence. Frequently, the rhombohedral unit

cell is reoriented so that it can be described on the basis

of a hexagonal unit cell (Azaroff, 1968). It can be consid-

ered a subsystem of the hexagonal system, and then one

speaks of only six crystal systems.

We can now assign the various point groups to the six

crystal systems. Point groups 1 and 1 obviously belong to

the triclinic system. All point groups with only one unique

2-fold axis belong to the monoclinic system. Thus, 2, 2 ¼ m,

and 2/m are monoclinic. Point groups like 222, mmm, etc.,

are orthorhombic; 32, 6, 6/mmm, etc., are hexagonal (point

groups with a 3-fold axis are also labeled trigonal); 4, 4/m,

422, etc., are tetragonal; and 23, m3m, and 432, are cubic.

Note the position of the 3-fold axis in the sequence of sym-

bols for the cubic system. The distribution of the 32 point

groups among the six crystal systems is shown in Figure 6.

The rhombohedral and trigonal systems are not counted

separately.

LATTICES

When the unit cell is translated along three periodically

repeated noncoplanar, noncollinear vectors, a three-

dimensional lattice of points is generated (Fig. 7). When

looking at such an array one can select an infinite number

of periodically repeated, noncollinear, noncoplanar vectors

t1, t2, and t3, in three dimensions, connecting two lattice

points, that will constitute the basis vectors of a unit cell

for such an array. The choice of a unit cell is one of conve-

nience, but usually the unit cell is chosen to reflect the

symmetry operators present. Each lattice point at the

eight corners of the unit cell is shared by eight other unit

cells. Thus, a unit cell has 8 Â 1

8 ¼ 1 lattice point. Such a

unit cell is called primitive and is given the symbol P.

One can choose nonprimitive unit cells that will contain

more than one lattice point. The array of atoms around

one lattice point is identical to the same array around

every other lattice point. This array of atoms may consist

either of molecules or of individual atoms, as in NaCl. In

the latter case the Naþ

and ClÀ

atoms are actually located

on lattice points. However, lattice points are usually not

occupied by atoms. Confusing lattice points with atoms is

a common beginners’ error.

In Table 1 the unit cells for the various crystal systems

are listed with the restrictions on the parameters as a

result of the presence of symmetry operators. Let the b-

axis of a coordinate system be a 2-fold axis. The ac coordi-

nate plane can have axes at any angle to each other: i.e., b

can have any value. But the b-axis must be perpendicular

to the ac plane or else the parallelogram defined by the vec-

tors a and b will not be repeated periodically. The presence

of the 2-fold axis imposes the restriction that a ¼ g ¼ 908.

Similarly, the presence of three 2-fold axes requires an

orthogonal unit cell. Other symmetry operators impose

further restrictions, as shown in Table 1.

Consider now a 2-fold b-axis perpendicular to a paralle-

logram lattice ac. How can this two-dimensional lattice be

Table 1. The Seven Crystal Systems

Crystal System Minimum Symmetry Unit Cell Parameter Relationships

Triclinic (anorthic) Only a 1-fold axis a 6¼ b 6¼ c; a 6¼ b 6¼ g

Monoclinic One 2-fold axis chosen to be the unique b-axis, [010] a 6¼ b 6¼ c; a ¼ g ¼ 90

; b 6¼ 90

Orthorhombic Three mutually perpendicular 2-fold axes, [100], [010], [001] a 6¼ b 6¼ c; a ¼ b ¼ g ¼ 90

Rhombohedrala

One 3-fold axis parallel to the long axis of the rhomb, [111] a ¼ b ¼ c; a ¼ b ¼ g 6¼ 90

Tetragonal One 4-fold axis parallel to the c-axis, [001] a ¼ b 6¼ c; a ¼ b ¼ g ¼ 90

Hexagonalb

One 6-fold axis parallel to the c-axis, [001] a ¼ b 6¼ c; a ¼ b ¼ 90

g ¼ 120

Cubic (isometric) Four 3-fold axes parallel to the four body diagonals of a cube, [111] a ¼ b ¼ c; a ¼ b ¼ g ¼ 90

a

Usually transformed to a hexagonal unit cell.

b

Point groups or space groups that are not rhombohedral but contain a 3-fold axis are labeled trigonal.

Figure 7. A point lattice with the outline of several possible unit

cells.

44 COMMON CONCEPTS](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/characterizationofmaterials-eltonn-kaufmann-130214165548-phpapp02-150817084749-lva1-app6891/85/Characterizationofmaterials-eltonn-kaufmann-130214165548-phpapp02-64-320.jpg)

![repeated along the third dimension? It cannot be along

some arbitrary direction because such a unit cell would

violate the 2-fold axis. However, the plane net can be

stacked along the b-axis at some definite interval to com-

plete the unit cell (Fig. 8A). This symmetry operation pro-

duces a primitive cell, P. Is this the only possibility? When

a 2-fold axis is periodically repeated in space with period a,

then the 2-fold axis at the origin is repeated at x ¼ 1, 2, . . .,

n, but such a repetition also gives rise to new 2-fold axes at

x ¼ 1

2 ; 3

2 ; . . . , z ¼ 1

2 ; 3

2 ; . . . , etc., and along the plane diagonal

(Fig. 9). Thus, there are three additional 2-fold axes and

three additional stacking possibilities along the 2-fold

axes located at x ¼ 1

2 ; z ¼ 0; x ¼ 0, z ¼ 1

2; and x ¼ 1

2, z ¼ 1

2.

However, the first layer stacked along the 2-fold axis

located at x ¼ 1

2, z ¼ 0 does not result in a unit cell that

incorporates the 2-fold axis. The vector from 0, 0, 0 to

that lattice point is not along a 2-fold axis. The stacking

sequence has to be repeated once more and now a lattice

point on the second parallelogram lattice will lie above

the point 0, 0, 0. The vector length from the origin to

that point is the periodicity along b. An examination of

this unit cell shows that there is a lattice point at 1

2, 1

2, 0

so that the ab face is centered. Such a unit cell is labeled

C-face centered given the symbol C (Fig. 8D), and contains

two lattice points: the origin lattice point shared among

eight cells and the face-centered point shared between

two cells. Stacking along the other 2-fold axes produces

an A-face-centered cell given the symbol A (Fig. 8C) and

a body-centered cell given the label I. (Fig. 8B). Since every

direction in the monoclinic system is a 1-fold axis except

for the 2-fold b-axis, the labeling of a and c directions in

the plane perpendicular to b is arbitrary. Interchanging

the a and c axial labels changes the A-face centering to

C-face centering. By convention C-face centering is the

standard orientation. Similarly, an I-centered lattice can

be reoriented to a C-centered cell by drawing a diagonal

in the old cell as a new axis. Thus, there are only two uni-

que Bravais lattices in the monoclinic system, Figure 10.

The systematic investigation of the combinations of the

32 point groups with periodic translation in space gener-

ates 14 different space lattices. The 14 Bravais lattices

are shown in Figure 10 (Azaroff, 1968; McKie and McKie,

1986).

Miller Indices

To explain x ray scattering from atomic arrays it is conve-

nient to think of atoms as populating planes in the unit

cell. The diffraction intensities are considered to arise

from reflections of these planes. These planes are labeled

by the inverse of their intercepts on the unit cell axes. If

a plane intercepts the a-axis at 1

2, the b-axis at 1

2, and the

c-axis at 2

3 the distances of their respective periodicities,

then the Miller indices are h ¼ 4, k ¼ 4, l ¼ 3, the recipro-

cals cleared of fractions (Fig. 11), and the plane is denoted

as (443). The round brackets enclosing the (hkl) indices

indicate that this is a plane. Figure 11 illustrates this con-

vention for several planes. Planes that are related by a

symmetry operator such as a 4-fold axis in the tetragonal

system are part of a common form. Thus, (100), (010), (100)

and (010) are designated by ((100)) or {100}. A direction in

the unit cell—e.g., the vector from the origin 0, 0, 0 to the

lattice point 1, 1, 1—is represented by square brackets as

[111]. Note that the above four planes intersect in a com-

mon line, the c-axis or the zone axis, which is designated as

[001]. A family of zone axes is indicated by angle brackets,

h111i. For the tetragonal system, this symbol denotes the

symmetry-equivalent directions [111], [111], [111], and

Figure 8. The stacking of parallelogram lattices in the monocli-

nic system. (A) Shifting the zero level up along the 2-fold axis

located at the origin of the parallelogram. (B) Shifting the zero

level up on the 2-fold axis at the center of the parallelogram. (C)

Shifting the zero level up on the 2-fold axis located at 1

2c. (D) Shift-

ing the zero level up on the 2-fold axis located at 1

2a. Courtesy of

Azaroff (1968).

Figure 9. A periodic repetition of a 2-fold axis creates new, crys-

tallographically independent 2-fold axes. Courtesy of Azaroff

(1968).

SYMMETRY IN CRYSTALLOGRAPHY 45](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/characterizationofmaterials-eltonn-kaufmann-130214165548-phpapp02-150817084749-lva1-app6891/85/Characterizationofmaterials-eltonn-kaufmann-130214165548-phpapp02-65-320.jpg)

![[111]. The plane (hkl) and the zone axis [uvw] obey the

relationship hu þ kw þ lz ¼ 0.

A complication arises in the hexagonal system. There

are three equivalent a-axes due to the presence of a 3-

fold or 6-fold symmetry axis perpendicular to the ab plane.

If the three axes are the vectors a1, a2, and a3, then a1 þ

a2 ¼ Àa3. To remove any ambiguity about which of the

axes are cut by a plane, four symbols are used. They are

the Miller-Bravais indices hkil, where i ¼ À(h þ k) (Azar-

off, 1968). Thus, what is ordinarily written as (111)

becomes in the hexagonal system (1121) or (11Á1), the

dot replacing the 2. The Miller indices for the unique direc-

tions in the unit cells of the seven crystal systems are listed

in Table 1.

SPACE GROUPS

The combination of the 32 crystallographic point groups

with the 14 Bravais lattices produces the 230 space groups.

The atomic arrangement of every crystalline material dis-

playing 3-dimensional periodicity can be assigned to one of

Figure 10. The 14 Bravais lattices. Courtesy of Cullity (1978).

46 COMMON CONCEPTS](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/characterizationofmaterials-eltonn-kaufmann-130214165548-phpapp02-150817084749-lva1-app6891/85/Characterizationofmaterials-eltonn-kaufmann-130214165548-phpapp02-66-320.jpg)

![Space Group Symbols

In general, space group notations consist of four symbols.

The first symbol always refers to the Bravais lattice. Why,

then, do we have P 1 or P 2/m? The full symbols are P111

and P 1 2/m 1. But in the triclinic system there is no unique

direction, since every direction is a 1-fold axis of symmetry.

It is therefore sufficient just to write P 1. In the monoclinic

system there is only one unique direction—by convention

it is the b-axis—and so only the symmetry elements

related to that direction need to be specified. In the orthor-

hombic system there are the three unique 2-fold axes par-

allel to the lattice parameters a, b, and c. Thus, Pnma

means that the crystal system is orthorhombic, the Bra-

vais lattice is P, and there is an n glide plane perpendicular

to the a-axis, a mirror perpendicular to the b-axis, and an a

glide plane perpendicular to the c-axis. The complete sym-

bol for this space group is P 21/n 21/m 21/a. Again, the 21

screw axes are a result of the other symmetry operators

and are not expressly indicated in the standard symbol.

The letter symbols are considered in the denominator

and the interpretation is that the operators are perpendi-

cular to the axes. In the tetragonal system there is the

unique direction, the 4-fold c-axis. The next unique direc-

tions are the equivalent a and b axes, and the third direc-

tions are the four equivalent C-face diagonals, the h110i

directions. The symbol I4cm means that the space group

is tetragonal, the Bravais lattice is body centered, there

is a 4-fold axis parallel to the c-axis, there is are c glide

planes perpendicular to the equivalent a and b-axes, and

there are mirrors perpendicular to the C-face diagonals.

Note that one can say just as well that the symmetry

operators c and m are parallel to the directions.

The symbol P3c1 tells us that the space group belongs to

the trigonal system, primitive Bravais lattice, with a 3-fold

rotoinversion axis parallel to the c-axis, and a c glide plane

perpendicular to the equivalent a and b axes (or parallel to

the [210] and [120] directions); the third symbol refers to

the face diagonal [110]. Why the 1 in this case? It serves

to distinguish this space group from the space group

P31c, which is different. As before, it is part of the trigonal

system. A 3 rotoinversion axis parallel to the c axis is pre-

sent, but now the c glide plane is perpendicular to the [110]

or parallel to the [110] directions. Since 6-fold symmetry

must be maintained there are also c glide planes parallel

to the a and b axes. The symbol R denotes the rhombohe-

dral Bravais lattice, but the lattice is usually reoriented so

that the unit cell is hexagonal.

The symbol Fm3m full symbol F 4/m 3 2/m, tells us that

this space group belongs to the cubic system (note the posi-

tion of 3), the Bravais lattice is all faces centered, and there

are mirrors perpendicular to the three equivalent a, b, and

c axes, a 3 rotoinversion axis parallel to the four body diag-

onals of the cube, the h111i directions, and a mirror per-

pendicular to the six equivalent face diagonals of the

cube, the h110i directions. In this space group additional

symmetry elements are generated, such as 4-fold, 2-fold,

and 21 axes.

Simple Example of the Use of Crystal Structure Knowledge

Of what use is knowledge of the space group for a crystal-

line material? The understanding of the physical and che-

mical properties of a material ultimately depends on the

knowledge of the atomic architecture—i.e., the location

of every atom in the unit cell with respect to the coordinate

axes. The density of a material is r ¼ M/V, where r is den-

sity, M the mass, and V the volume (see MASS AND DENSITY

MEASUREMENTS). The macroscopic quantities can also be ex-

pressed in terms of the atomic content of the unit cell. The

mass in the unit cell volume V is the formula weight M

multiplied by the number of formula weights z in the unit

cell divided by Avogadro’s number N. Thus, r ¼ Mz/VN.

Consider NaCl. It is cubic, the space group is Fm3m, the

unit cell parameter is a ¼ 4.872 A˚ , its density is 2.165 g/

cm3

, and its formula weight is 58.44, so that z ¼ 4. There

are four Na and four Cl ions in the unit cell. The general

position x y z in space group Fm3m gives rise to a total of

191 additional equivalent positions. Obviously, one cannot

place an Na atom into a general position. An examination

of the space group table shows that there are two special

positions with four equipoints labeled 4a, at 0, 0, 0 and

4b, at 1

2, 1

2, 1

2. Remember that F means that x ¼ 1

2, y ¼ 1

2,

z ¼ 0; x ¼ 0, y ¼ 1

2, z ¼ 1

2; and x ¼ 1

2, y ¼ 0, z ¼ 1

2 must be added

to the positions. Thus, the 4 Naþ

atoms can be located at

the 4a position and the 4 ClÀ

atoms at the 4b position,

and since the positional parameters are fixed, the crystal

structure of NaCl has been determined. Of course, this is

a very simple case. In general, the determination of the

space group from x-ray diffraction data is the first essen-

tial step in a crystal structure determination.

CONCLUSION

It is hoped that this discussion of symmetry will ease the

introduction of the novice to this admittedly arcane topic

or serve as a review for those who want to extend their

expertise in the area of space groups.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author gratefully acknowledges the support of the

Robert A. Welch Foundation of Houston, Texas.

LITERATURE CITED

Azaroff, L. A. 1968. Elements of X-Ray Crystallography. McGraw-

Hill, New York.

Buerger, M. J. 1956. Elementary Crystallography. John Wiley

Sons, New York.

Buerger, M. J. 1970. Contemporary Crystallography. McGraw-

Hill, New York.

Burns, G. and Glazer, A. M. 1978. Space Groups for Solid State

Scientists. Academic Press, New York.

Cullity, B. D. 1978. Elements of X-Ray Diffraction, 2nd ed.

Addison-Wesley, Reading, Mass.

Giacovazzo, C., Monaco, H. L., Viterbo, D., Scordari, F., Gilli, G.,

Zanotti, G., and Catti, M. 1992. Fundamentals of Crystallogra-

phy. International Union of Crystallography, Oxford Univer-

sity Press, Oxford.

Hall, L. H. 1969. Group Theory and Symmetry in Chemistry.

McGraw-Hill, New York.

50 COMMON CONCEPTS](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/characterizationofmaterials-eltonn-kaufmann-130214165548-phpapp02-150817084749-lva1-app6891/85/Characterizationofmaterials-eltonn-kaufmann-130214165548-phpapp02-70-320.jpg)

![of unit magnitude traveling from left to right along the

horizontal axis, striking the target at the origin, and

leaving at angles and energies indicated by the scattering

circle. The circle passes through the point (1,08), corre-

sponding to the situation where no collision occurs. Of

course, when there is no scattering (ys ¼ 08), there is no

change in the incident particle’s energy or velocity (Es ¼

1 and vs ¼ 1). The maximum energy loss occurs at y ¼

1808, when a head-on collision occurs. The circle center

and radius are a function of the target-to-projectile mass

ratio. The center is located along the 08 direction a distance

xs from the origin, given by

xs ¼

1

1 þ A

ð11Þ

while the radius for elastic scattering is

rs ¼ 1 À xs ¼ A xs ¼

A

1 þ A

ð12Þ

For inelastic scattering, the scattering circle center is also

given by Equation 11, but the radius is given by

rs ¼ fAxs ¼

fA

1 þ A

ð13Þ

where f is defined as in Equation 10.

Equation 11 and Equation 12 or 13 make it easy to con-

struct the appropriate scattering circle for any given mass

ratio A. One simply uses Equation 11 to find the circle cen-

ter at (xs,08) and then draws a circle of radius rs. The result-

ing scattering circle can then be used to find the energy of

the scattered particle at any scattering angle by drawing a

line from the origin to the circle at the selected angle. The

length of the line is H(Es).

Similarly, the polar coordinates for recoiling are

([H(Er)],yr), where Er ¼ E2/E0. A typical elastic recoiling

circle is shown in Figure 3. The recoiling circle passes

through the origin, corresponding to the case where no

collision occurs and the target remains at rest. The circle

center, xr, is located at:

xr ¼

ffiffiffiffi

A

p

1 þ A

ð14Þ

and its radius is rr ¼ xr for elastic recoiling or

rr ¼ fxr ¼

f

ffiffiffiffi

A

p

1 þ A

ð15Þ

for inelastic recoiling.

Recoiling circles can be readily constructed for any col-

lision partners using the above equations. For elastic colli-

sions ( f ¼ 1), the construction is trivial, as the recoiling

circle radius equals its center distance.

Figure 4 shows elastic scattering and recoiling circles

for a variety of mass ratio A values. Since the circles are

symmetric about the horizontal (08) direction, only semi-

circles are plotted (scattering curves in the upper half

plane and recoiling curves in the lower quadrant). Several

general properties of binary collisions are evident. First,

Figure 2. An elastic scattering circle plotted in polar coordinates

(HE; y) where E is Es ¼ E1/E0 and y is the laboratory scattering

angle, ys. The length of the line segment from the origin to a point

on the circle gives the relative scattered particle velocity, vs, at

that angle. Note that HðEsÞ ¼ vs ¼ v1/v0. Scattering circles are cen-

tered at (xs,08), where xs ¼ (1 þ A)À1

and A ¼ m2/m1. All elastic

scattering circles pass through the point (1,08). The circle shown

is for the case A ¼ 4. The triangle illustrates the relationships

sin(yc À ys)/sin(ys) ¼ xs/rs ¼ 1/A.

Figure 3. An elastic recoiling circle plotted in polar coordinates

(HE,y) where E is Er ¼ E2/E0 and y is the laboratory recoiling angle,

yr. The length of the line segment from the origin to a point on the

circle gives HðErÞ at that angle. Recoiling circles are centered at

(xr,08), where xr ¼ HA/(1 þ A). Note that xr ¼ rr. All elastic recoil-

ing circles pass through the origin. The circle shown is for the case

A ¼ 4. The triangle illustrates the relationship yr ¼ (p À yc)/2.

PARTICLE SCATTERING 53](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/characterizationofmaterials-eltonn-kaufmann-130214165548-phpapp02-150817084749-lva1-app6891/85/Characterizationofmaterials-eltonn-kaufmann-130214165548-phpapp02-73-320.jpg)

![ultrasonicator. Polishing is accomplished using medium-

nap cloths, first with a 0.5-mm a-alumina abrasive and

then with a 0.03-mm g-alumina abrasive. The holder

should be cleaned in an ultrasonicator between these two

steps. A wheel speed of 300 rpm should be used, and the

specimen should be rotated counter to the wheel rotation.

Polishing requires 10 min for the first step and 5 min for

the second step.

SEM Examination. The objective is to image the anodized

layer in backscattered electron mode and measure its

thickness. This step is best accomplished using an as-

polished surface.

Etching. Etching is required to reveal the microstruc-

ture in a T6 state (solution heat treated and artificially

aged). Keller’s reagent (2 mL 48% HF/3 mL concentrated

HCl/5 mL concentrated HNO3/190 mL H2O) can be used

to distinguish between T4 (solution heat treated and natu-

rally aged to a substantially stable condition) and T6 heat

treatment; supplementary electrical conductivity mea-

surements will also aid in distinguishing between T4 and

T6. The microstructure should also be checked against

standard sources in the literature, however.

Microstructural Evaluation of Deformed

High-Purity Aluminum

A sample preparation procedure is needed for a high

volume of extremely soft samples that were previously

deformed and partially recrystallized. The objective is to

produce samples with no artifacts and to reveal the fine

substructure associated with the thermomechanical his-

tory.

There was no in-house experience and an initial survey

of the metallographic literature for high-purity aluminum

did not reveal a previously developed technique. A broader

literature search that included Ph.D. dissertations uncov-

ered a successful procedure (Connell, 1972). The methodol-

ogy is sufficiently detailed so that only slight in-

house adjustments are needed to develop a fast and highly

reliable sample preparation procedure.

Sectioning. The aim is to avoid excessive deformation of

the extremely soft samples. A continuous-loop wire saw

should be used with a silicon-carbide abrasive slurry. The

1/4-in. (0.6-cm) section will be cut in 10 min.

Mounting. In order to avoid any microstructural recov-

ery effects, the sample should be mounted at room tem-

perature. An electrical contact is required for subsequent

electropolishing; an epoxy mount with an embedded elec-

trical contact could be used. Multiple epoxy mounts should

be cured overnight in a cool chamber.

Mechanical Abrasion. Semiautomatic abrasion and pol-

ishing is suggested. Grinding begins with 600-grit silicon

carbide, using water as lubricant. The wheel is rotated at

150 rpm, and the sample is held counter to wheel rotation

and rinsed after grinding. This step takes $5 min.

Mechanical Polishing. The objective is to produce a sur-

face suitable for electropolishing and etching. After

mechanical abrasion, and between the two polishing steps,

the holder and samples should be cleaned in an ultrasoni-

cator. Polishing is accomplished using medium-nap cloths,

first with 1200- and then 3200-mesh emery in soap solu-

tion. A wheel speed of 300 rpm should be used, and the

holder should be rotated counter to the wheel rotation.

Mechanical polishing requires 10 min for the first step

and 5 min for the second step.

Electrolytic Polishing and Etching. The aim is to reveal

the microstructure without metallographic artifacts. An

electrolyte containing 8.2 cm3

HF, 4.5 g boric acid, and

250 cm3

deionized water is suggested. A chlorine-free gra-

phite cathode should used, with an anode-cathode spacing

of 2.5 cm and low agitation. The open circuit voltage should

be 20 V. The time needed for polishing is 30 to 40 s with an

additional 15 to 25 s for etching.

COMMENTARY

These examples emphasize two points. The first is the

importance of a conducting thorough literature search

before developing a new sample preparation procedure.

The second is that any attempt to categorize metallo-

graphic procedures through a series of simple steps can

misrepresent the field. Instead, an attempt has been

made to give the reader an overview with selected exam-

ples of various complexity. While these metallographic

sample preparation procedures were written with the lay-

man in mind, the literature and Internet sources should be

useful for practicing metallographers.

LITERATURE CITED

Anosov, P.P. 1954. Collected Works. Akademiya Nauk SSR, Mos-

cow.

ASM Handbook Committee. 1985. ASM Metals Handbook Volume

9: Metallography and Microstructures. ASM International,

Metals Park, Ohio.

Connell, R.G. Jr. 1972. The Microstructural Evolution of Alumi-

num During the Course of High-Temperature Creep. Ph.D.

thesis, University of Florida, Gainesville.

Rhines, F.N. 1968. Introduction. In Quantitative Microscopy (R.T.

DeHoff and F.N. Rhines, eds.) pp. 1-10. McGraw-Hill, New

York.

Sorby, H.C. 1864. On a new method of illustrating the structure of

various kinds of steel by nature printing. Sheffield Lit. Phil.

Soc., Feb. 1964.

Vander Voort, G. 1984. Metallography: Principle and Practice.

McGraw-Hill, New York.

KEY REFERENCES

Books

Huppmann, W.J. and Dalal, K. 1986. Metallographic Atlas of Pow-

der Metallurgy. Verlag Schmid. [Order from Metal Powder

Industries Foundation, Princeton, N.J.]

Comprehensive compendium of powder metallurgical microstruc-

tures.

SAMPLE PREPARATION FOR METALLOGRAPHY 69](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/characterizationofmaterials-eltonn-kaufmann-130214165548-phpapp02-150817084749-lva1-app6891/85/Characterizationofmaterials-eltonn-kaufmann-130214165548-phpapp02-89-320.jpg)

![However, it would be unwise to chalk up the rapid pro-

gress of computational modeling solely to the availability

of cheaper and faster computers. Even more significant

for the progress of this field may be the algorithmic devel-

opment for simulation and quantum mechanical techni-

ques. Highly accurate implementations of the local

density approximation (LDA) to quantum mechanics

[and its extension to the generalized gradient approxima-

tion (GGA)] are now widely available. They are consider-

ably faster and much more accurate now than only a few

years ago. The Car-Parrinello method and related algo-

rithms have significantly improved the equilibration of

quantum mechanical systems (Car and Parrinello, 1985;

Payne et al., 1992). There is no reason to expect this trend

to stop, and it is likely that the most significant advances

in computational materials science will be realized

through novel methods development rather than from

ultra-high-performance computing.

Significant challenges remain. In many cases the accu-

racy of ab initio methods is orders of magnitude less than

that of experimental methods. For example, in the calcula-

tion of phase diagrams an error of 10 meV, not large at all

by ab initio standards, corresponds to an error of more

than 100 K.

The time and size scales over which materials phenom-

ena occur remain the most significant challenge. Although

the smallest size scale in a first-principles method is

always that of the atom and electron, the largest size scale

at which individual features matter for a macroscopic

property may be many orders of magnitude larger. For

example, microstructure formation ultimately originates

from atomic displacements, but the system becomes inho-

mogeneous on the scale of micrometers through sporadic

nucleation and growth of distinct crystal orientations or

phases. Whereas statistical mechanics provide guidance

on how to obtain macroscopic averages for properties in

homogeneous systems, there is no theory for coarse-grain

(average) inhomogeneous materials. Unfortunately, most

real materials are inhomogeneous.

Finally, all the power of computational materials

science is worth little without a general understanding of

its basic methods by all materials researchers. The rapid

development of computational modeling has not been par-

alleled by its integration into educational curricula. Few

undergraduate or even graduate programs incorporate

computational methods into their curriculum, and their

absence from traditional textbooks in materials science

and engineering is noticeable. As a result, modeling is still

a highly undervalued tool that so far has gone largely

unnoticed by much of the materials science and engineer-

ing community in universities and industry. Given its

potential, however, computational modeling may be

expected to become an efficient and powerful research

tool in materials science and engineering.

LITERATURE CITED

Abraham, F. F. 1997. On the transition from brittle to plastic fail-

ure in breaking a nanocrystal under tension (NUT). Europhys.

Lett. 38:103–106.

Aydinol, M. K., Kohan, A. F., Ceder, G., Cho, K., and Joannopou-

los, J. 1997. Ab-initio study of litihum intercalation in metal

oxides and metal dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. B 56:1354–1365.

Car, R. and Parrinello, M. 1985. Unified approach for molecular

dynamics and density functional theory. Phys. Rev. Lett.

55:2471–2474.

Ceder, G. 1993. A derivation of the Ising model for the computa-

tion of phase diagrams. Computat. Mater. Sci. 1:144–150.

de Fontaine, D. 1994. Cluster approach to order-disorder transfor-

mations in alloys. In Solid State Physics (H. Ehrenreich and

D. Turnbull, eds.). pp. 33–176. Academic Press, San Diego.

Ducastelle, F. 1991. Order and Phase Stability in Alloys. North-

Holland Publishing, Amsterdam.

Eberhart, M. E. 1996. A chemical approach to ductile versus brit-

tle phenomena. Philos. Mag. A 73:47–60.

Fox, G. C. and Coddington, P. D. 1993. An overview of high perfor-

mance computing for the physical sciences. In High Perfor-

mance Computing and Its Applications in the Physical

Sciences: Proceedings of the Mardi Gras ‘93 Conference (D. A.

Browne et al., eds.). pp. 1–21. World Scientific, Louisiana State

University.

Ohzuku, T. and Atsushi, U. 1994. Why transitional metal (di) oxi-

des are the most attractive materials for batteries. Solid State

Ionics 69:201–211.

Payne, M. C., Teter, M. P., Allan, D. C., Arias, T. A., and Joan-

nopoulos, J. D. 1992. Iterative minimization techniques for

ab-initio total energy calculations: Molecular dynamics and

conjugate gradients. Rev. Mod. Phys. 64:1045.

Zunger, A. 1994. First-principles statistical mechanics of semicon-

ductor alloys and intermetallic compounds. In Statics and

Dynamics of Alloy Phase Transformations (P. E. A. Turchi

and A. Gonis, eds.). pp. 361–419. Plenum, New York.

GERBRAND CEDER

Massachusetts Institute of

Technology

Cambridge, Massachusetts

SUMMARY OF ELECTRONIC

STRUCTURE METHODS

INTRODUCTION

Most physical properties of interest in the solid state are

governed by the electronic structure—that is, by the Cou-

lombic interactions of the electrons with themselves and

with the nuclei. Because the nuclei are much heavier, it

is usually sufficient to treat them as fixed. Under this

Born-Oppenheimer approximation, the Schro¨dinger equa-

tion reduces to an equation of motion for the electrons in a

fixed external potential, namely, the electrostatic potential

of the nuclei (additional interactions, such as an external

magnetic field, may be added).

Once the Schro¨dinger equation has been solved for a

given system, many kinds of materials properties can be

calculated. Ground-state properties include the cohesive

energy, or heats of compound formation, elastic constants

or phonon frequencies (Giannozzi and de Gironcoli, 1991),

atomic and crystalline structure, defect formation ener-

gies, diffusion and catalysis barriers (Blo¨chl et al., 1993)

and even nuclear tunneling rates (Katsnelson et al.,

74 COMPUTATION AND THEORETICAL METHODS](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/characterizationofmaterials-eltonn-kaufmann-130214165548-phpapp02-150817084749-lva1-app6891/85/Characterizationofmaterials-eltonn-kaufmann-130214165548-phpapp02-94-320.jpg)

![when the lower (bonding) portion is filled and the upper

(antibonding) portion is empty. Except for Fe (and with

the mild exception of Mn, which has a complex structure

with noncollinear magnetic moments and was not consid-

ered here), each structure is correctly predicted, including

resolution of the experimentally observed sign of the hcp-

fcc energy difference. Even when calculated magnetically,

Fe is incorrectly predicted to be fcc. The GGAs of Langreth

and Mehl (1981) and Perdew and Wang (Perdew, 1991)

rectify this error (Bagno et al., 1989), possibly because

the bcc magnetic moment, and thus the magnetic

exchange energy, is overestimated for those functionals.

In an early calculation of structural energy differences

(Pettifor, 1970), Pettifor compared his results to inferences

of the differences by Kaufman who used ‘‘judicious use of

thermodynamic data and observations of phase equilibria

in binary systems.’’ Pettifor found that his calculated dif-

ferences are two to three times larger than what Kaufman

inferred (Paxton’s newer calculations produces still larger

discrepancies). There is no easy way to determine which is

more correct.

Figure 6 shows some calculated heats of formation for

the TiAl alloy. From the point of view of the electronic

structure, the alloy potential may be thought of as a rather

weak perturbation to the crystalline one, namely, a permu-

tation of nuclear charges into different arrangements on

the same lattice (and additionally some small distortions

about the ideal lattice positions). The deviation from the

regular solution model is properly reproduced by the

LDA, but there is a tendency to overbind, which leads to

an overestimate of the critical temperatures in the alloy

phase diagram (Asta et al., 1992).

LDA Elastic Constants

Because of the strong volume dependence of the elastic

constants, the accuracy to which LDA predicts them

depends on whether they are evaluated at the observed

volume or the LDA volume. Figure 7 shows both for the

elemental transition metals and some sp-bonded com-

pounds. Overall, the GGA of Langreth and Mehl (1981)

improves on the LDA; how much improvement depends

on which lattice constant one takes. The accuracy of other

elastic constants and phonon frequencies are similar (Bar-

oni et al., 1987; Savrosov et al., 1994); typically they are

predicted to within $20% for d-shell metals and somewhat

better than that for sp-bonded compounds. See Figure 8 for

a comparison of c44, or its hexagonal analog.

LDA Magnetic Properties

Magnetic moments in the itinerant magnets (e.g., the 3d

transition metals) are generally well predicted by the

LDA. The upper right panel of Figure 9 compares the

LDA moments to experiment both at the LDA minimum-

energy volume and at the observed volume. For magnetic

properties, it is most sensible to fix the volume to experi-

ment, since for the magnetic structure the nuclei may by

viewed as an external potential. The classical GGA

functionals of Langreth and Mehl (1981) and Perdew and

Wang (Perdew, 1991) tend to overestimate the moments

and worsen agreement with experiment. This is less

the case with the recent PBE functional, however,

as Figure 9 shows.

Cr is an interesting case because it is antiferromagnetic

along the [001] direction, with a spin-density wave, as Fig-

ure 9 shows. It originates as a consequence of a nesting

vector in the Cr Fermi surface (also shown in the figure),

which is incommensurate with the lattice. The half-period

is approximately the reciprocal of the difference in the

length of the nesting vector in the figure and the half-

width of the Brillouin zone. It is experimentally $21.2

monolayers (ML) (Fawcett, 1988), corresponding to a nest-

ing vector q ¼ 1:047. Recently, Hirai (1997) calculated the

Figure 5. Hexagonal close packedÀface centered cubic (hcp-fcc;

circles) and body centered cubicÀface centered cubic (bcc-fcc;

squares) structural energy differences, in meV, for the 3-d transi-

tion metals, as calculated in the LDA, using the full-potential

LMTO method. Original calculations are nonmagnetic (Paxton

et al., 1990; Skriver, 1985); white circles are recalculations by

the present author, with spin-polarization included.

Figure 6. Heat of formation of compounds of Ti and Al from the

fcc elemental states. Circles and hexagons are experimental data,

taken from Kubaschewski and Dench (1955) and Kubaschewski

and Heymer (1960). Light squares are heats of formation of com-

pounds from the fcc elemental solids, as calculated from the LDA.

Dark squares are the minimum-energy structures and correspond

to experimentally observed phases. Dashed line is the estimated

heat formation of a random alloy. Calculated values are taken

from Asta et al. (1992).

SUMMARY OF ELECTRONIC STRUCTURE METHODS 81](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/characterizationofmaterials-eltonn-kaufmann-130214165548-phpapp02-150817084749-lva1-app6891/85/Characterizationofmaterials-eltonn-kaufmann-130214165548-phpapp02-101-320.jpg)

![period in Cr by constructing long supercells and evaluat-

ing the total energy using a layer KKR technique as a func-

tion of the cell dimensions. The calculated moment

amplitude (Fig. 9) and period were both in good agreement

with experiment. Hirai’s calculated period was $20.8 ML,

in perhaps fortuitously good agreement with experiment.

This offers an especially rigorous test of the LDA, because

small inaccuracies in the Fermi surface are greatly magni-

fied by errors in the period.

Finally, Figure 9 shows the spin-wave spectrum in Fe

as calculated in the LDA using the atomic spheres approx-

imation and a Green’s function technique, plotted along

high-symmetry lines in the Brillouin zone. The spin stiff-

ness D is the curvature of o at À, and is calculated to be

330 meV-A2

, in good agreement with the measured 280–

310 meV-A2

. The four lines also show how the spectrum

would change with different band fillings (as defined in

the legend)—this is a ‘‘rigid band’’ approximation to alloy-

ing of Fe with Mn (EF 0) or Co (EF 0). It is seen that o is

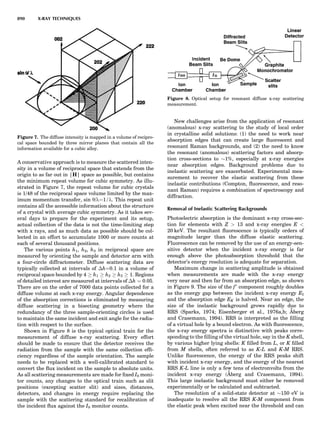

positive everywhere for the normal Fe case (black line),

and this represents a triumph for the LDA, since it demon-

strates that the global ground state of bcc Fe is the ferro-

magnetic one. o remains positive by shifting the Fermi

level in the ‘‘Co alloy’’ direction, as is observed experimen-

tally. However, changing the filling by only À0.2 eV (‘‘Mn

alloy’’) is sufficient to produce an instability at H, thus

driving it to an antiferromagnetic structure in the [001]

direction, as is experimentally observed.

Optical Properties

In the LDA, in contradistinction to Hartree-Fock theory,

there is no formal justification for associating the eigenva-

lues e of Equation 5 with energy bands. However, because

the LDA is related to Hartree-Fock theory, it is reasonable

to expect that the LDA eigenvalues e bear a close resem-

blance to energy bands, and they are widely interpreted

that way. There have been a few ‘‘proper’’ local-density cal-

culations of energy gaps, calculated by the total energy dif-

ference of a neutral and a singly charged molecule; see, for

example, Cappellini et al. (1997) for such a calculation in

C60 and Na4. The LDA systematically underestimates

bandgaps by $1 to 2 eV in the itinerant semiconductors;

the situation dramatically worsens in more correlated

materials, notably f-shell metals and some of the late-

transition-metal oxides. In Hartree-Fock theory, the non-

local exchange potential is too large because it neglects the

ability of the host to screen out the bare Coulomb interac-

tion 1=jr À r0

j. In the LDA, the nonlocal character of the

interaction is simply missing. In semiconductors, the

long-ranged part of this interaction should be present

but screened by the dielectric constant e1. Since e1 ) 1,

the LDA does better by ignoring the nonlocal interaction

altogether than does Hartree-Fock theory by putting it in

unscreened.

Harrison’s model of the gap underestimate provides us

with a clear physical picture of the missing ingredient in

the LDA and a semiquantitative estimate for the correc-

tion (Harrison, 1985). The LDA uses a fixed one-electron

potential for all the energy bands; that is, the effective

one-electron potential is unchanged for an electron excited

across the gap. Thus, it neglects the electrostatic energy

cost associated with the separation of electron and hole

for such an excitation. This was modeled by Harrison by

noting a Coulombic repulsion U between the local excess

charge and the excited electron. An estimate of this

Figure 9. Upper left: LDA Fermi surface

of nonmagnetic Cr. Arrows mark the nest-

ing vectors connecting large, nearly paral-

lel sheets in the Brillouin zone. Upper

right: magnetic moments of the 3-d transi-

tion metals, in Bohr magnetons, calculated

in the LDA at the LDA volume, at the

observed volume, and using the PBE

(Perdew et al., 1996, 1997) GGA at the

observed volume. The Cr data is taken

from Hirai (1997). Lower left: the magnetic

moments in successive atomic layers along

[001] in Cr, showing the antiferromagnetic

spin-density wave. The observed period is

$21.2 lattice spacings. Lower right: spin-

wave spectrum in Fe, in meV, calculated

in the LDA (Antropov et al., unpub.

observ.) for different band fillings, as dis-

cussed in the text.

SUMMARY OF ELECTRONIC STRUCTURE METHODS 83](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/characterizationofmaterials-eltonn-kaufmann-130214165548-phpapp02-150817084749-lva1-app6891/85/Characterizationofmaterials-eltonn-kaufmann-130214165548-phpapp02-103-320.jpg)

![and more accurate for ordering on the fcc lattice because it

contains next-nearest-neighbor (nnn) pairs, which are

important when considering associated effective pair

interactions (see below). Today, CVM entropy formulas

can be derived ‘‘automatically’’ for arbitrary lattices

and cluster schemes by computer codes based on group

theory considerations. The choice of the proper cluster

scheme to use is not a simple matter, although there now

exist heuristic methods for selecting ‘‘good’’ clusters (Vul

and de Fontaine, 1993; Finel, 1994).

The realization that configurational entropy in disor-

dered systems was really a many-body thermodynamic

expression led to the introduction of cluster probabilities

in free energy functionals. In turn, cluster variables led

to the development of a very useful cluster algebra, to be

described very briefly here [see the original article (San-

chez et al., 1984) or various reviews (e.g., de Fontaine,

1994) for more details]. The basic idea was to develop com-

plete orthonormal sets of cluster functions for expanding

arbitrary functions of configurations, a sort of Fourier

expansion for disordered systems. For simplicity, only bin-

ary systems will be considered here, without explicit con-

sideration of sublattices. As will become apparent, the

cluster algebra applied to the replacive (or configurational)

energy leads quite naturally to a precise definition of effec-

tive cluster interactions, similar to the phenomenological

w parameters of MF equations 8 and 9. With such a rigor-

ous definition available, it will be in principle possible to

calculate those parameters from ‘‘first principles,’’ i.e.,

from the knowledge of only the atomic numbers of

the constituents.

Any function of configuration f (r) can be expanded in a

set of cluster functions as follows (Sanchez et al., 1984):

fðsÞ ¼

X

a

FaÈaðsÞ ð21Þ

where the summation is over all clusters of lattice points (a

designating a cluster of na points of a certain geometrical

type: tetrahedron, square, . . .), Fa are the expansion

coefficients, and the Èa are suitably defined cluster func-

tions. The cluster functions may be chosen in an infinity

of ways but must form a complete set (Asta et al., 1991;

Wolverton et al., 1991a; de Fontaine et al., 1994). In the

binary case, the cluster functions may be chosen as pro-

ducts of s variables (¼ Æ1) over the cluster sites. The

sets may even be chosen orthonormal, in which case the

expansion (Equation 21) may be ‘‘inverted’’ to yield the

cluster coefficients

Fa ¼ r0

X

s

fðsÞÈaðsÞ hÈa; fi ð22Þ

where the summation is now over all possible 2N

configura-

tions and r0 is a suitable normalization factor. More gener-

al formulations have been given recently (Sanchez, 1993),

but these simple formulas, Equations 21 and 22, will suf-

fice to illustrate the method. Note that the formalism is

exact and moreover computationally useful if series con-

vergence is sufficiently rapid. In turn, this means that

the burden and difficulty of treating disordered systems

can now be carried by the determination of the cluster coef-

ficients Fa . An analogy may be useful here: in solving lin-

ear partial differential equations, for example, one

generally does not ‘‘solve’’ directly for the unknown func-

tion; one instead describes it by its representation in a

complete set of functions, and the burden of the work is

then carried by the determination of the coefficients of

the expansion.

The most important application of the cluster expan-

sion formalism is surely the calculation of the configura-

tional energy of an alloy, though the technique can also

be used to obtain such thermodynamic quantities as molar

volume, vibrational entropy, and elastic moduli as a func-

tion of configuration. In particular, application of Equation

21 to the configurational energy E provides an exact

expression for the expansion coefficients, called effective

cluster interactions, or ECIs, Va . In the case of pair inter-

actions (for lattice sites p and q, say), the effective pair

interaction is given by

Vpq ¼ 1

4 ð EAA þ EBB À EAB À EBAÞ ð23Þ

where EIJ (I, J ¼ A or B) is the average energy of all con-

figurations having atom of type I at site p and of type J at

q. Hence, it is seen that the Va parameters, those required

by the Ising model thermodynamics, are by no means ‘‘pair

potentials,’’ as they were often referred to in the past, but

differences of energies, which can in fact be calculated.

Generalizations of Equation 23 can be obtained for multi-

plet interactions such as Vpqr as a function of AAA, AAB,

etc., average energies, and so on.

How, then, does one go about calculating the pair or

cluster interactions in practice? One method makes use

of the orthogonality property explicitly by calculating the

average energies appearing in Equation 23. To be sure, not

all possible configurations r are summed over, as required

by Equation 22, but a sampling is taken of, say, a few tens

of configurations selected at random around a given IJ

Figure 7. Various CVM approximations in the symbolic Kikuchi

notation.

98 COMPUTATION AND THEORETICAL METHODS](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/characterizationofmaterials-eltonn-kaufmann-130214165548-phpapp02-150817084749-lva1-app6891/85/Characterizationofmaterials-eltonn-kaufmann-130214165548-phpapp02-118-320.jpg)

![limit, products of xA and xB must also be introduced in the

cluster probabilities appearing in the configurational

entropy. It is found that, for any cluster probability, the

logarithmic terms in Equation 29 reduce to n[xA log xA þ

xB log xB], precisely the MF (ideal) entropy term in Equa-

tion 7 multiplied by the number n of points in the cluster,

thereby showing that the sum of the Kikuchi-Barker coef-

ficients, weighted by n, must equal À1. This simple prop-

erty may be used to verify the validity of a newly derived

CVM entropy expression; it also shows that the type, or

shape, of the clusters is irrelevant to the MF model, as

only the number of points matters. This is another demon-

stration that the MF approximation ignores the true geo-

metry of local atomic arrangements.

Note that, strictly speaking, the CVM is also a MF form-

alism, but it treats the correlations (almost) correctly for

lattice distances included within the largest cluster consid-

ered in the approximation and includes SRO effects. Hence

the CVM is a multisite MF model, whereas the ‘‘point’’ MF

is a single-site model, the one previously referred to as the

MF (ideal, regular solution, GBW, concentration wave,

etc.) model.

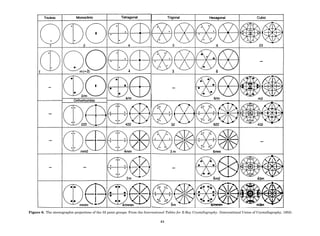

It has been seen that the MF model is the same as the

CVM point approximation, and the MF free energy can be

derived by making the superposition ansatz, xAB ! xAxB,

xAAB ! x2

AxB, and so on. Of course, the point is very

much simpler to handle than the ‘‘cluster’’ formalism. So

how much is lost in terms of actual phase diagram results

in going from MF to CVM? To answer that question, it is

instructive to consider a very striking yet simple example,

the case of ordering on the fcc lattice with only first-neigh-

bor effective pair interactions (de Fontaine, 1979). The MF

phase diagram of Figure 8A was constructed by the GBW

MF approximation (Shockley, 1938), that of Figure 8B by

the CVM in the tetrahedron approximation, whose sym-

bolic formula is given in Figure 7 (de Fontaine, 1979, based

on van Baal, 1973, and Kikuchi, 1974). It is seen that, even

in a topological sense, the two diagrams are completely dif-

ferent: the GBW diagram (only half of the concentration

axis is represented) shows a double second-order transi-

tion at the central composition (xB ¼ 0.5), whereas the

CVM diagram shows three first-order transitions for the

three ordered phases A3B, AB3 (L12-type ordered struc-

ture), and AB (L10). The short horizontal lines in Figure

8B are tie lines, as seen in Figure 1. The two very small

three-phase regions are actually peritectic-like, topolo-

gically, as in Figure 1B.

There can be no doubt about which prototype diagram is

correct, at least qualitatively: the CVM version, which in

turn is very similar to the solid-state portion of the experi-

mental Cu-Au phase diagram (Massalski, 1986; in this

particular case, the first edition is to be preferred). The

large discrepancy between the MF and CVM versions

arises mainly from the basic geometrical figure of the fcc

lattice being the nn equilateral triangle (and the asso-

ciated nn tetrahedron). Such a figure leads to frustration

where, as in this case, the first nn interaction favors unlike

atomic pairs. This requirement can be satisfied for two of

the nn pairs making up the triangle, but the third pair

must necessarily be a ‘‘like’’ pair, hence the conflict. This

frustration also lowers the transition temperature below

what it would be in nonfrustrated systems. The cause of

the problem with the MF approach is of course that it

does not ‘‘know about’’ the triangle figure and the fru-

strated nature of its interactions. Numerically, also, the

CVM configurational entropy is much more accurate

than the GBW (MF), particularly if higher-cluster approx-

imations are used.

These are not the only reasons for using the cluster

approach: the cluster expansion provides a rigorous formu-

lation for the ECI; see Equation 23 and extensions thereof.

That means that the ECIs for the replacive (or strictly con-

figurational) energy can now be considered not only as fit-

ting parameters but also as quantities that can be

rigorously calculated ab initio. Such atomistic computa-

tions are very difficult to perform, as they involve electro-

nic structure calculations, but much progress has been

realized in recent years, as briefly summarized in the

next section.

Figure 8. (A) Left half of fcc ordering phase diagram (full lines)

with nn pair interactions in the GBW approximation; from de Fon-

taine (1979), according to W. Shockley (1938). Dotted and dashed

lines are, respectively, loci of equality of free energies for disor-

dered and ordered A3B (L12) phases (so-called T0 line) and order-

ing spinodal (not used in this unit). (B) The fcc ordering phase

diagram with nn pair interactions in the CVM approximation;

from de Fontaine (1979), according to C.M. van Baal (1973) and

R. Kikuchi (1974).

100 COMPUTATION AND THEORETICAL METHODS](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/characterizationofmaterials-eltonn-kaufmann-130214165548-phpapp02-150817084749-lva1-app6891/85/Characterizationofmaterials-eltonn-kaufmann-130214165548-phpapp02-120-320.jpg)

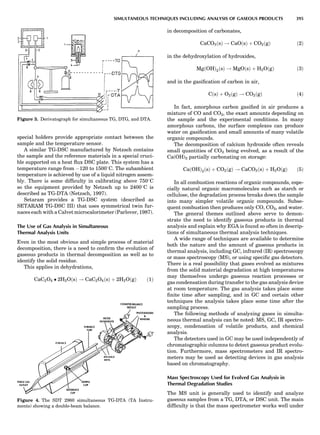

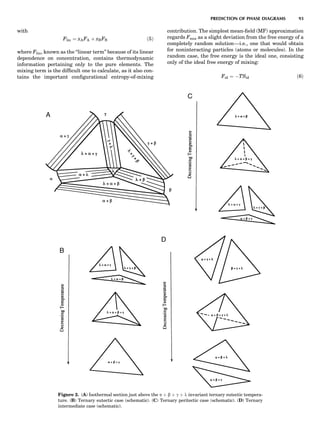

![Electronic Structure Calculations

One of most important breakthroughs in condensed-mat-

ter theory occurred in the mid-1960s with the development

of the (exact) density functional theory (DFT) and its local

density approximation (LDA), which provided feasible

means for performing large-scale electronic structure cal-

culations. It then took almost 20 years for practical and

reliable computer codes to be developed and implemented

on fast computers. Today many fully developed codes are

readily accessible and run quite well on workstations, at

least for moderate-size applications. Figure 9 introduces

the uninitiated reader to some of the alphabet soup of elec-

tronic structure theory relevant to the subject at hand.

What the various methods have in common is solving

the Schro¨dinger equation (sometimes the Dirac equation)

in an electronically self-consistent manner in the local den-

sity approximation. The methods differ from one another

in the choice of basis functions used in solving the relevant

linear differential equation—augmented plane waves

[(A)PW], muffin tin orbitals (MTOs), atomic orbitals in

the tight binding (TB) method—generally implemented

in a non-self-consistent manner. The methods also differ

in the approximations used to represent the potential

that an electron sees in the crystal or molecule, F or FP,

designating ‘‘full potential.’’ The symbol L designates a lin-

earization of the eigenvalue problem, a characteristic not

present in the ‘‘multiple-scattering’’ KKR (Korringa-

Kohn-Rostocker) method. The atomic sphere approxima-

tion (ASA) is a very convenient simplification that makes

the LMTO-ASA (linear muffin tin orbital in the ASA) a

particularly efficient self-consistent method to use,

although not as reliable in accuracy as the full-potential

methods. Another distinction is that pseudopotential

methods define separate ‘‘potentials’’ for s, p, d, ... , valence

states, whereas the other self-consistent techniques are

‘‘all-electron’’ methods. Finally, note that plane-wave basis

methods (pseudopotential, FLAPW) are the most conveni-

ent ones to use whenever forces on atoms need to be

calculated. This is an important consideration as correct

cohesive energies require that total energies be minimized

with respect to lattice ‘‘constants’’ and possible local atomic

displacements as well.

There is not universal agreement concerning the defini-

tion of ‘‘first-principles’’ calculations. To clarify the situa-

tion, let us define levels of ab initio character:

First level: Only the z values (atomic numbers) are

needed to perform the electronic structure calculation,

and electronic self-consistency is performed as part of the

calculation via the density functional approach in the LDA.

This is the most fundamental level; it is that of the APW,

LMTO, and ab initio pseudopotentials. One can also use

semiempirical pseudopotentials, whose parameters may

be fitted partially to experimental data.

Second level: Electronic structure calculations are per-

formed that do not feature electronic self-consistency.

Then the Hamiltonian must be expressed in terms of para-

meters that must be introduced ‘‘from the outside.’’ An

example is the TB method, where indeed the Schro¨dinger

equation is solved (the Hamiltonian is diagonalized, the

eigenvalues summed up), and the TB parameters are cal-

culated separately from a level 1 formulation, either from

LMTO-ASA, which can give these parameters directly

(hopping integrals, on-site energies) or by fitting to the

electronic band structure calculated, for example, by a

level 1 theory. The TB formulation is very convenient,

can treat thousands of atoms, and often gives valuable

band structure energies. Total energies, for which repul-

sive terms must be constructed by empirical means, are

not straightforward to obtain. Thus, a typical level 2

approach is the combined LMTO-TB procedure.

Third level: Empirical potentials are obtained directly

by fitting properties (cohesive energies, formation ener-

gies, elastic constants, lattice parameters) to experimen-

tally measured ones or to those calculated by level 1

methods. At level 3, the ‘‘potentials’’ can be derived in prin-

ciple from electronic structure but are in fact (partially)

obtained by fitting. No attempt is made to solve the Schro¨-

dinger equation itself. Examples of such approaches are

the embedded-atom method (EAM) and the TB method

inthesecond-momentapproximation(referencesgivenlater).

Fourth level: Here the interatomic potentials are

strictly empirical and the total energy, for example, is

obtained by summing up pair energies. Molecular

dynamics (MD) simulations operate with fourth- or third-

level approaches, with the exception of the famous Car-

Parrinello method, which performs ab initio molecular

dynamics, combining MD with the level 1 approach.

In Figure 9, arrows emanate from electronic structure

calculations, converging on the ECIs, and then lead to

Monte Carlo simulation and/or the CVM, two forms of sta-

tistical thermodynamic calculations. This indicates the

central role played by the ECIs in ‘‘first-principles thermo-

dynamics.’’ Three main paths lead to the ECIs: (a) DCA,

based on the explicit application of Equations 22 and 23;

(b) the SIM, based on solution of the linear system 24;

and (c) methods based on the CPA (coherent potential

approximation). These various techniques are described

in some detail elsewhere (de Fontaine, 1994), where

Figure 9. Flow chart for obtaining ECI from electronic structure

calculations. Pot potentials.