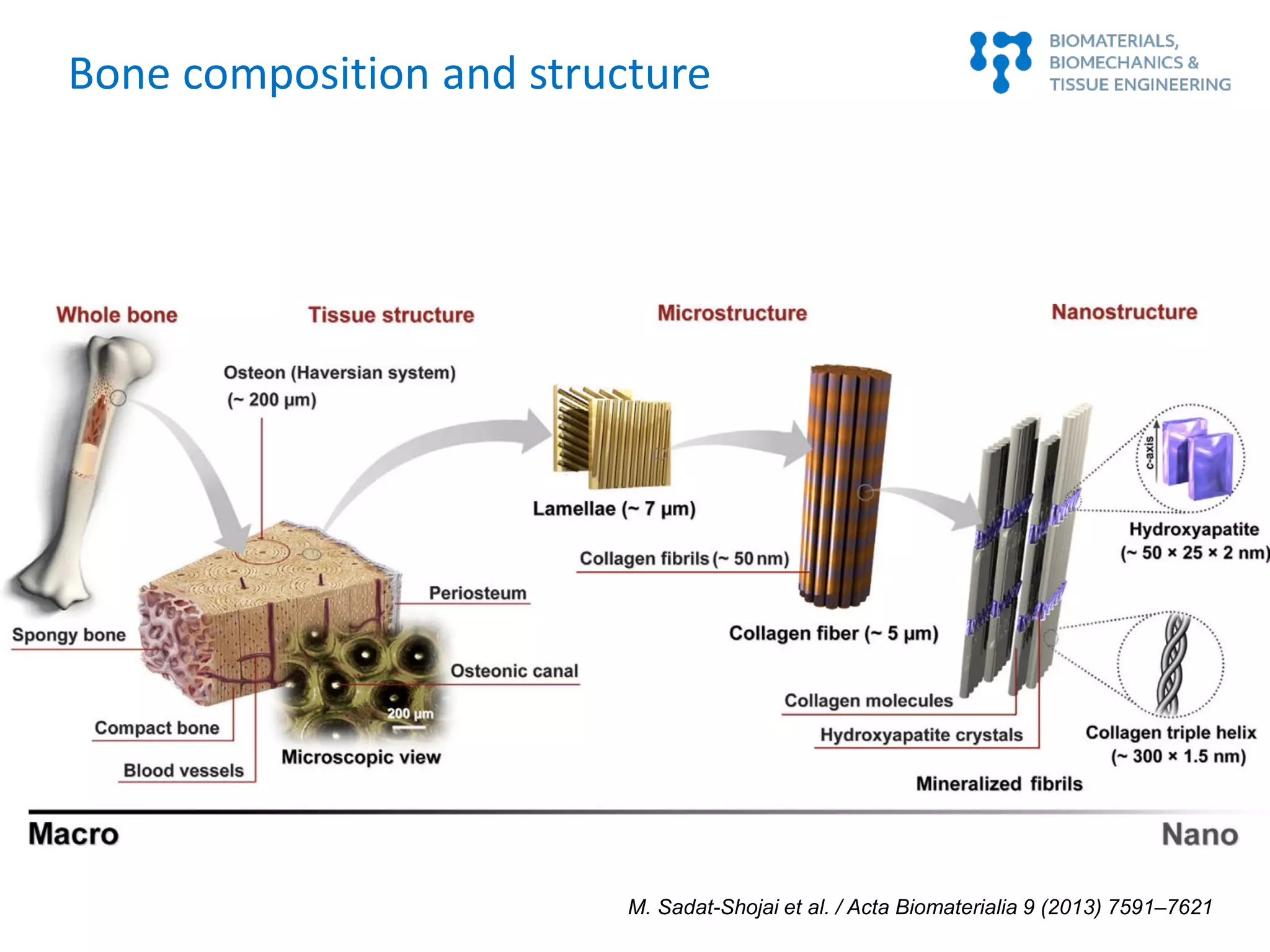

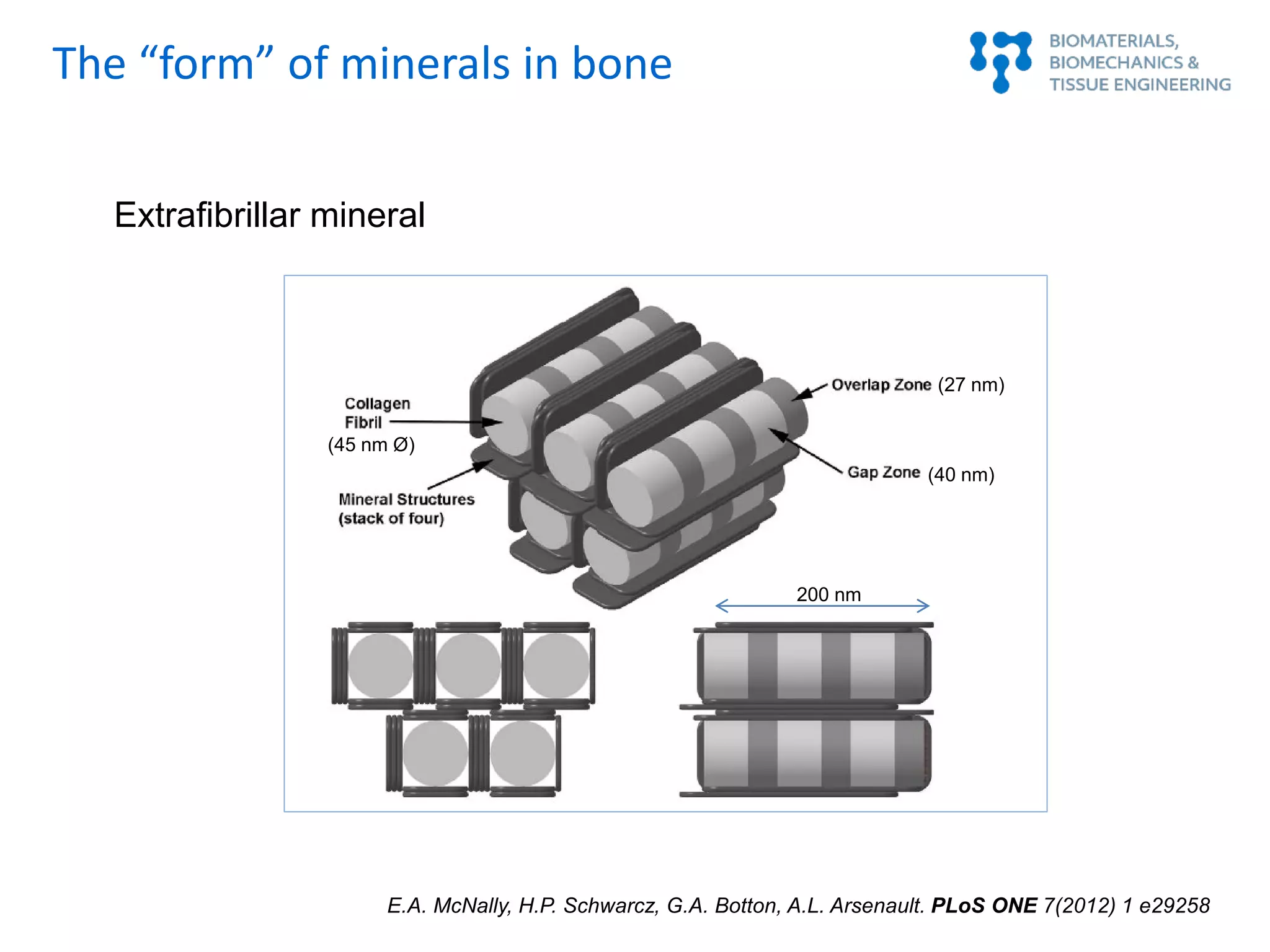

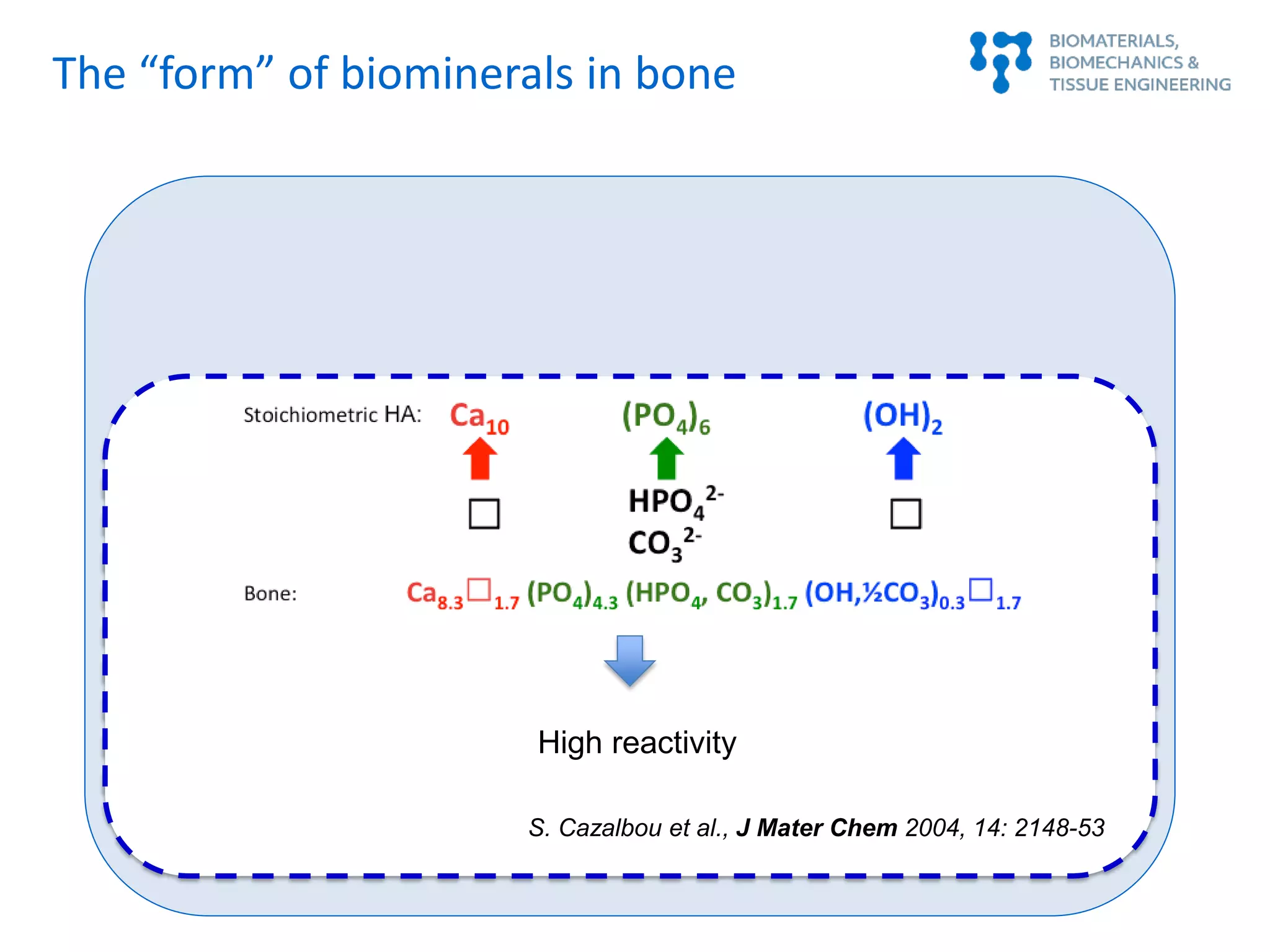

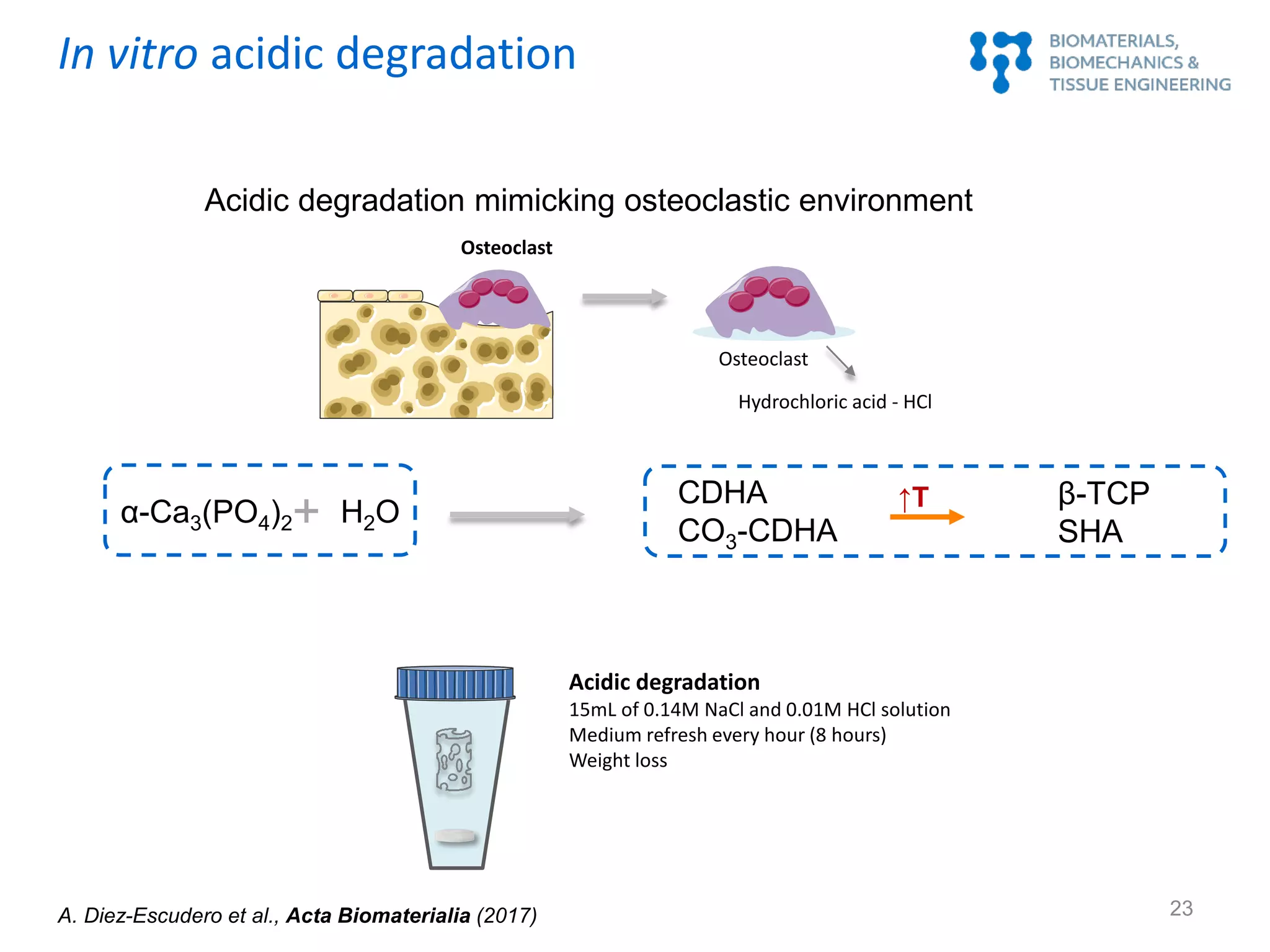

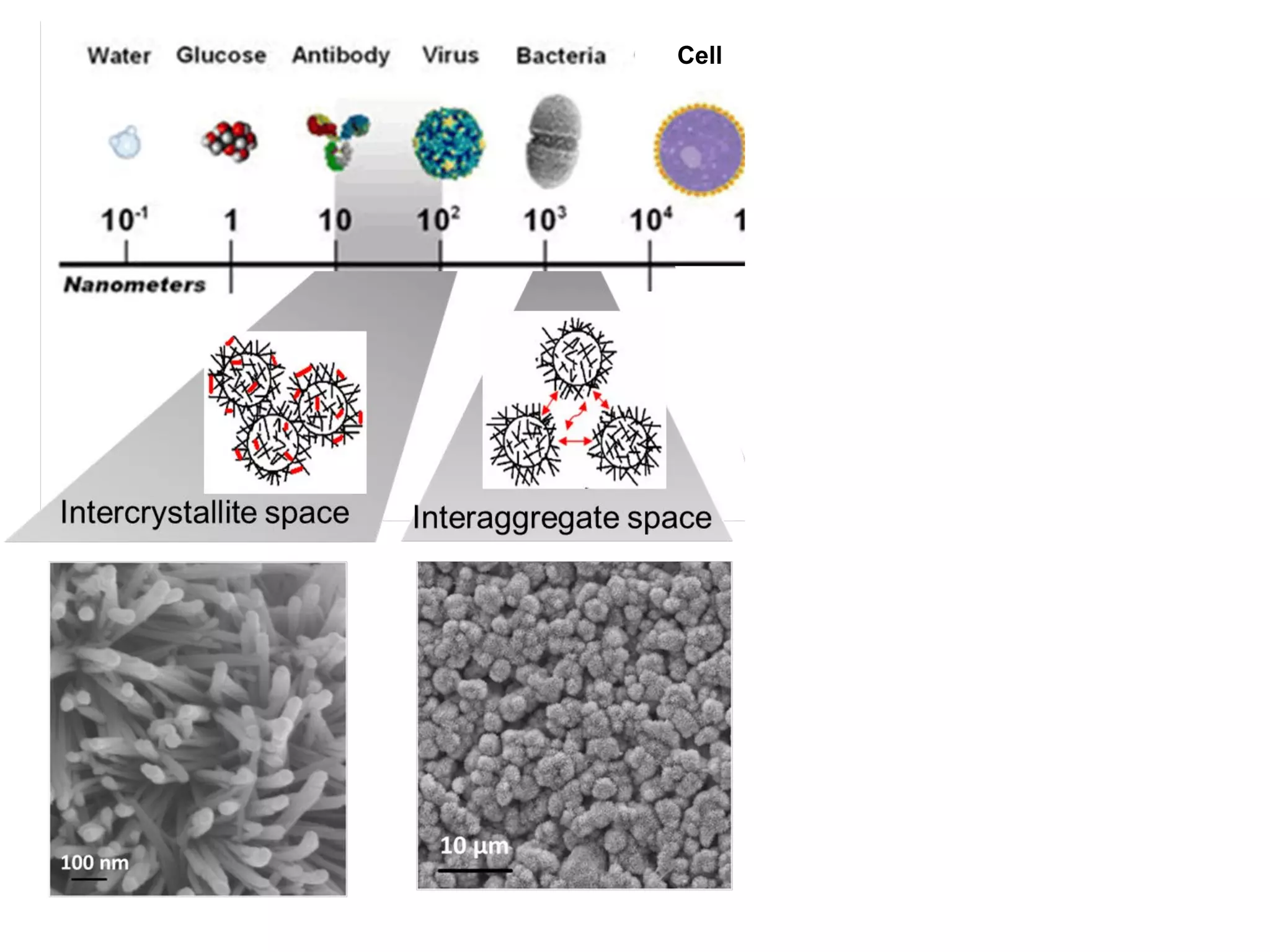

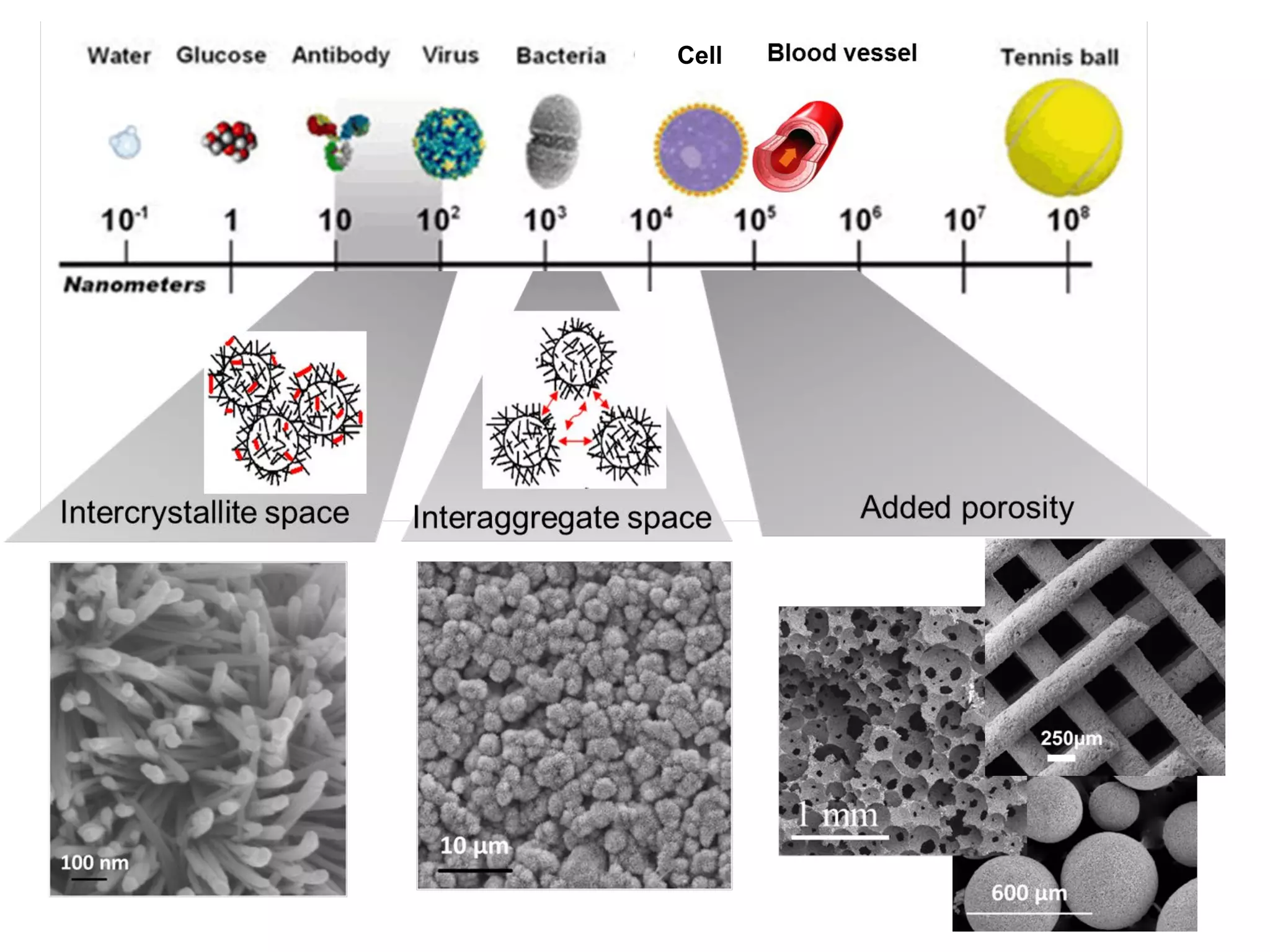

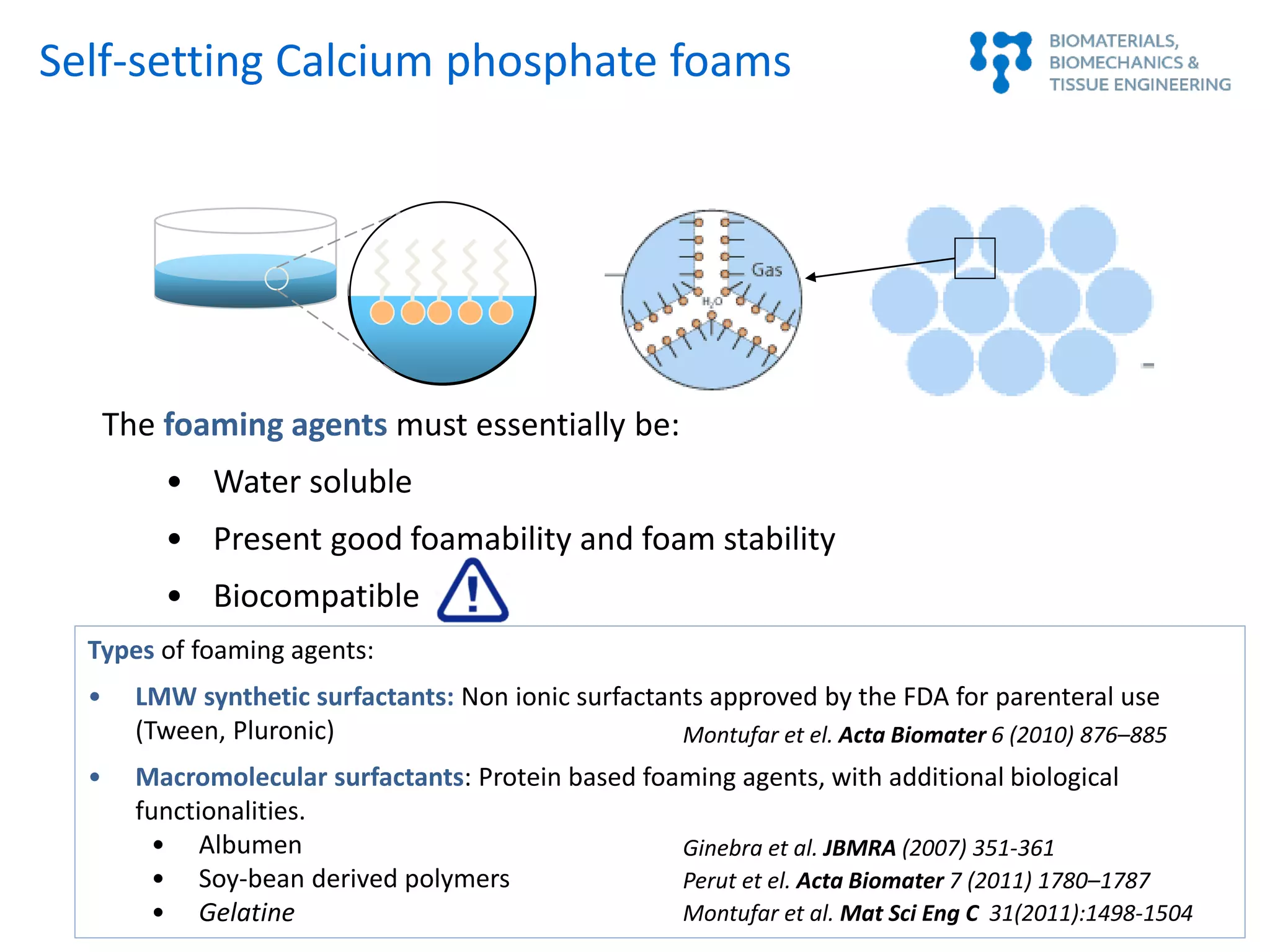

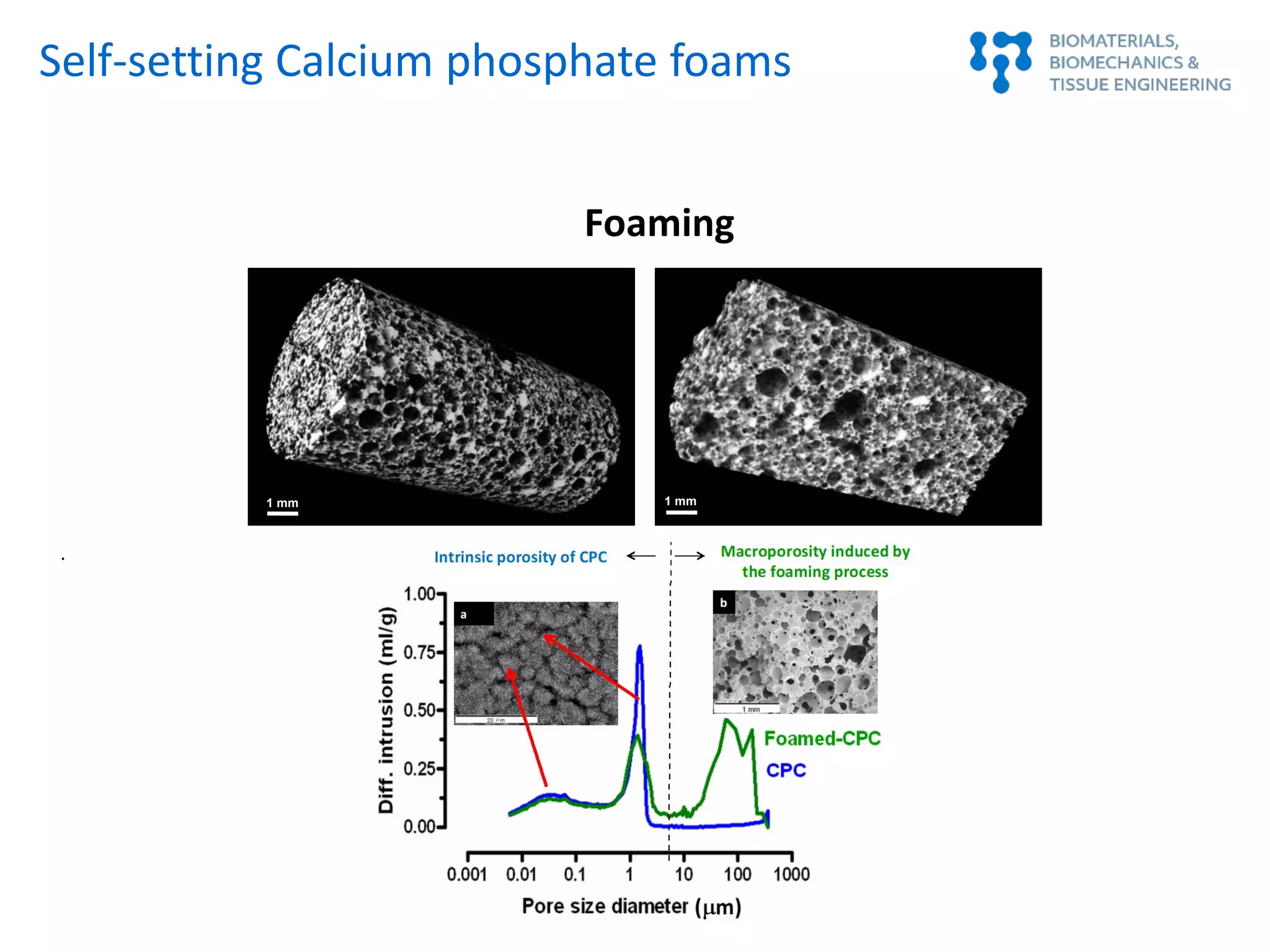

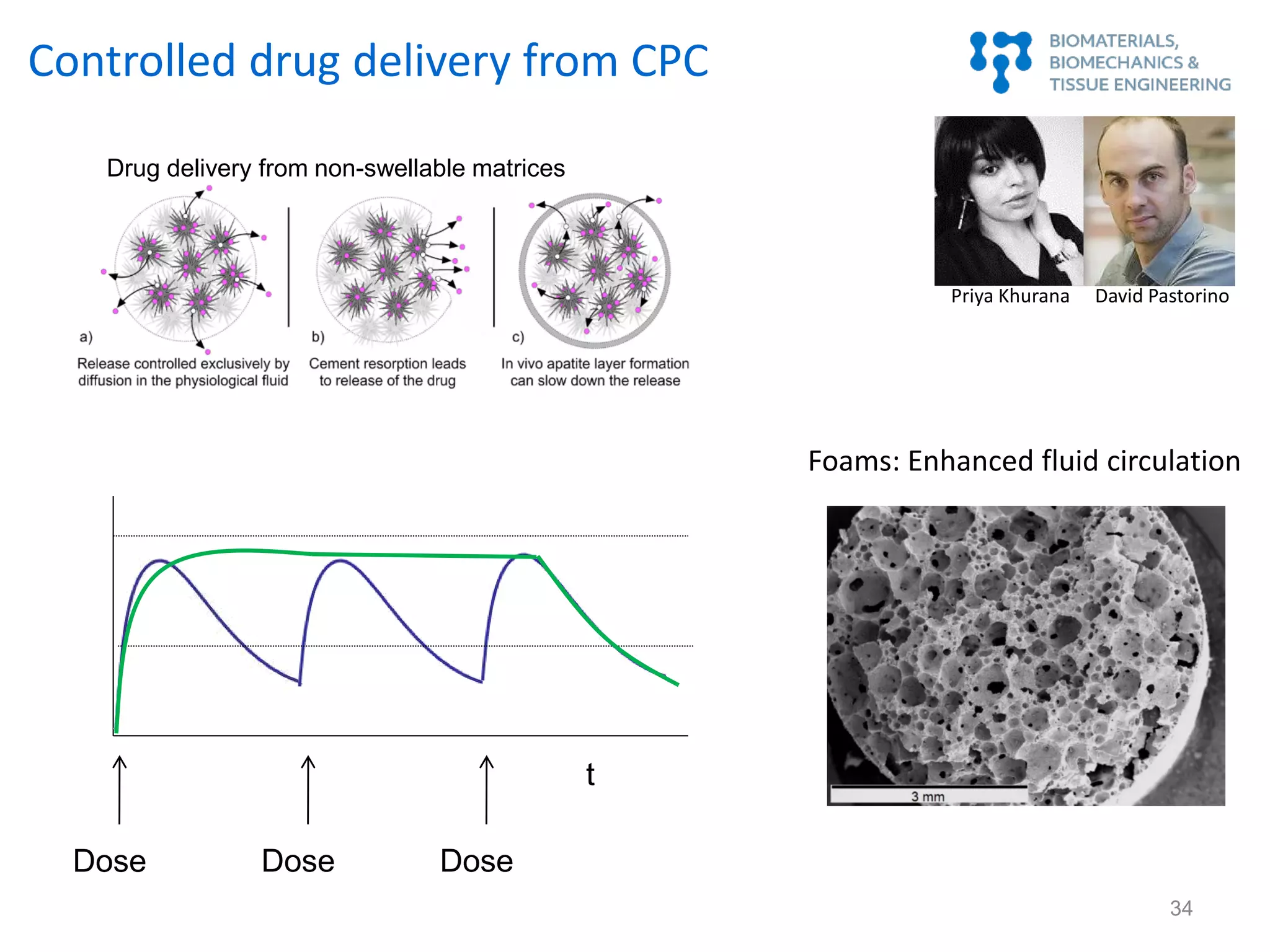

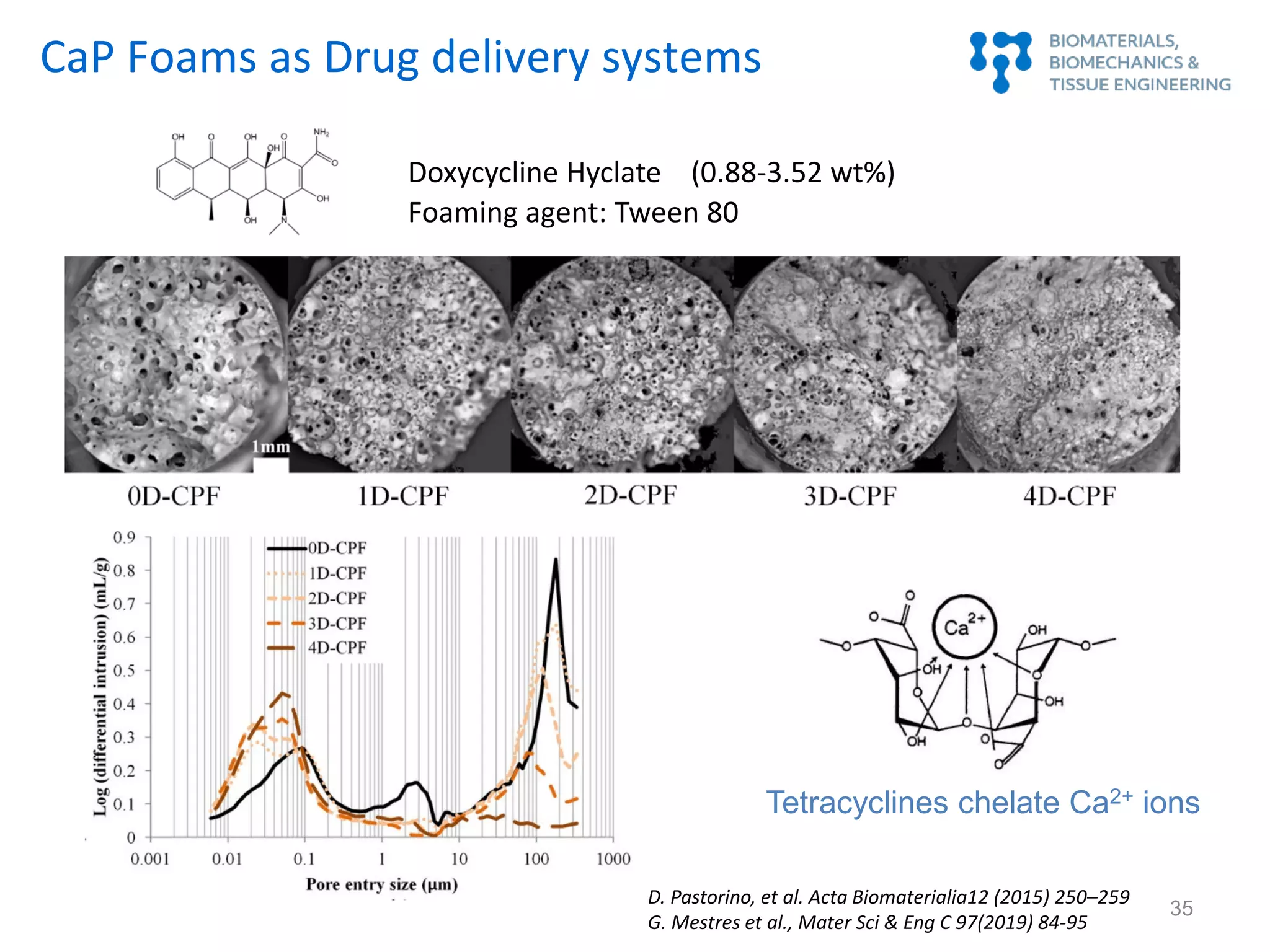

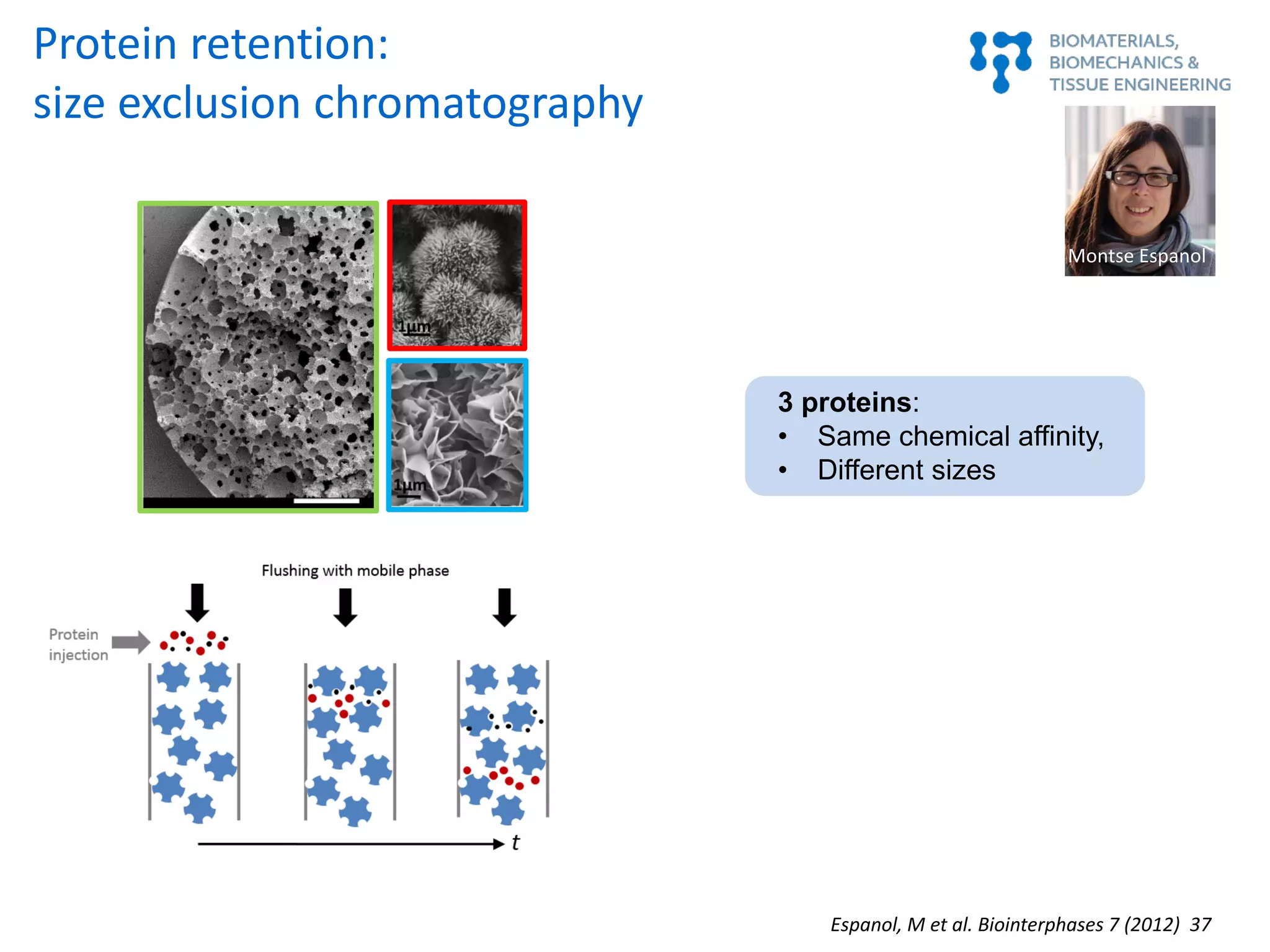

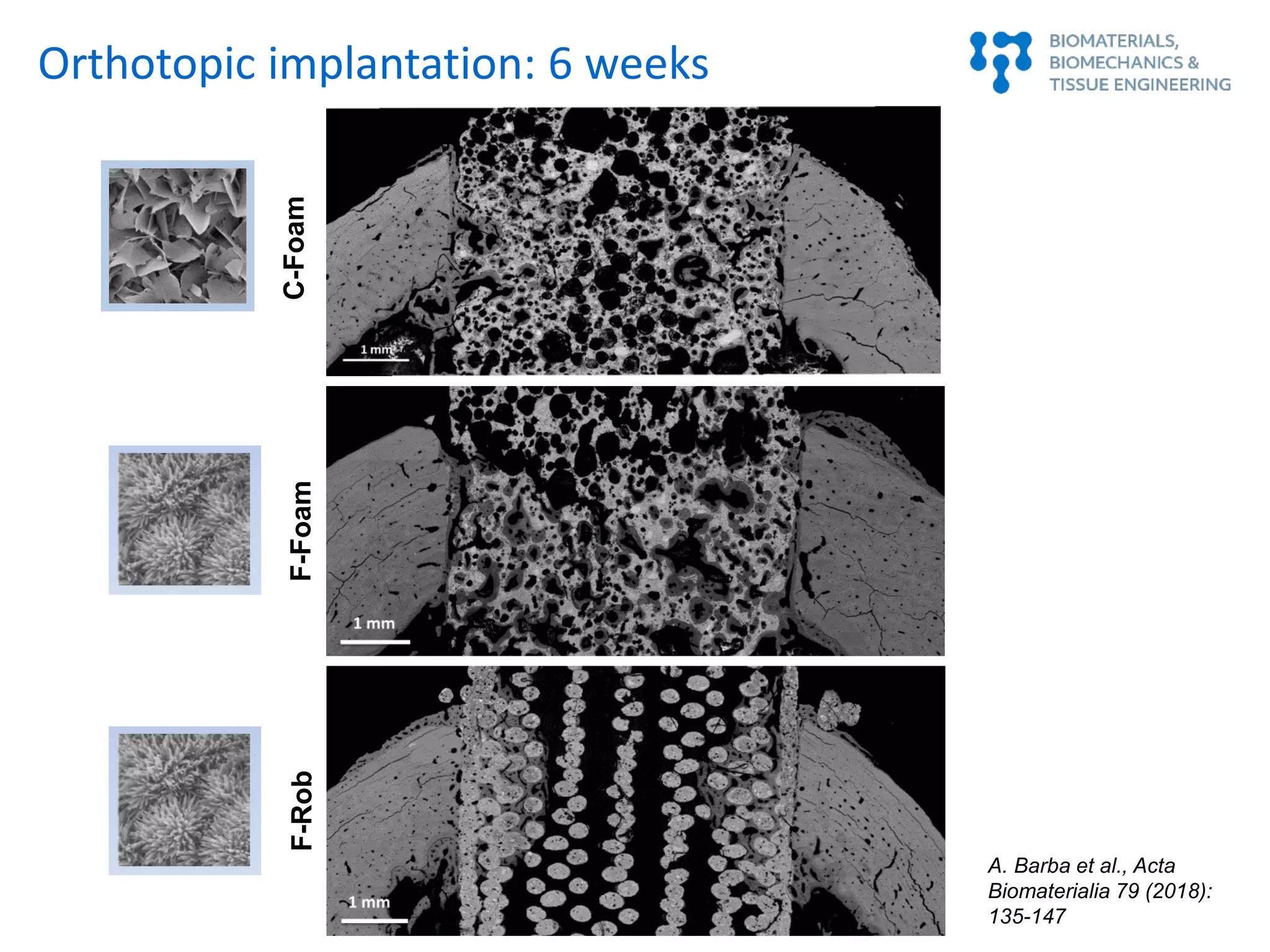

This document summarizes a presentation on bioinspired strategies for bone regeneration. It discusses how biomimetic calcium phosphate materials can mimic bone's composition, structure, and properties at multiple length scales to promote bone regeneration. Specifically, it describes how biomimetic calcium phosphates with nanostructured features and interconnected macroporosity can enhance osteoinduction, osteogenesis, and osteoimmunomodulation both in vitro and in vivo compared to conventional calcium phosphate ceramics. The document provides examples of how biomimetic calcium phosphate foams and 3D printed scaffolds regenerate bone in preclinical studies better than controls due to their ability to intrinsically induce bone formation through their biomimetic design.

![67

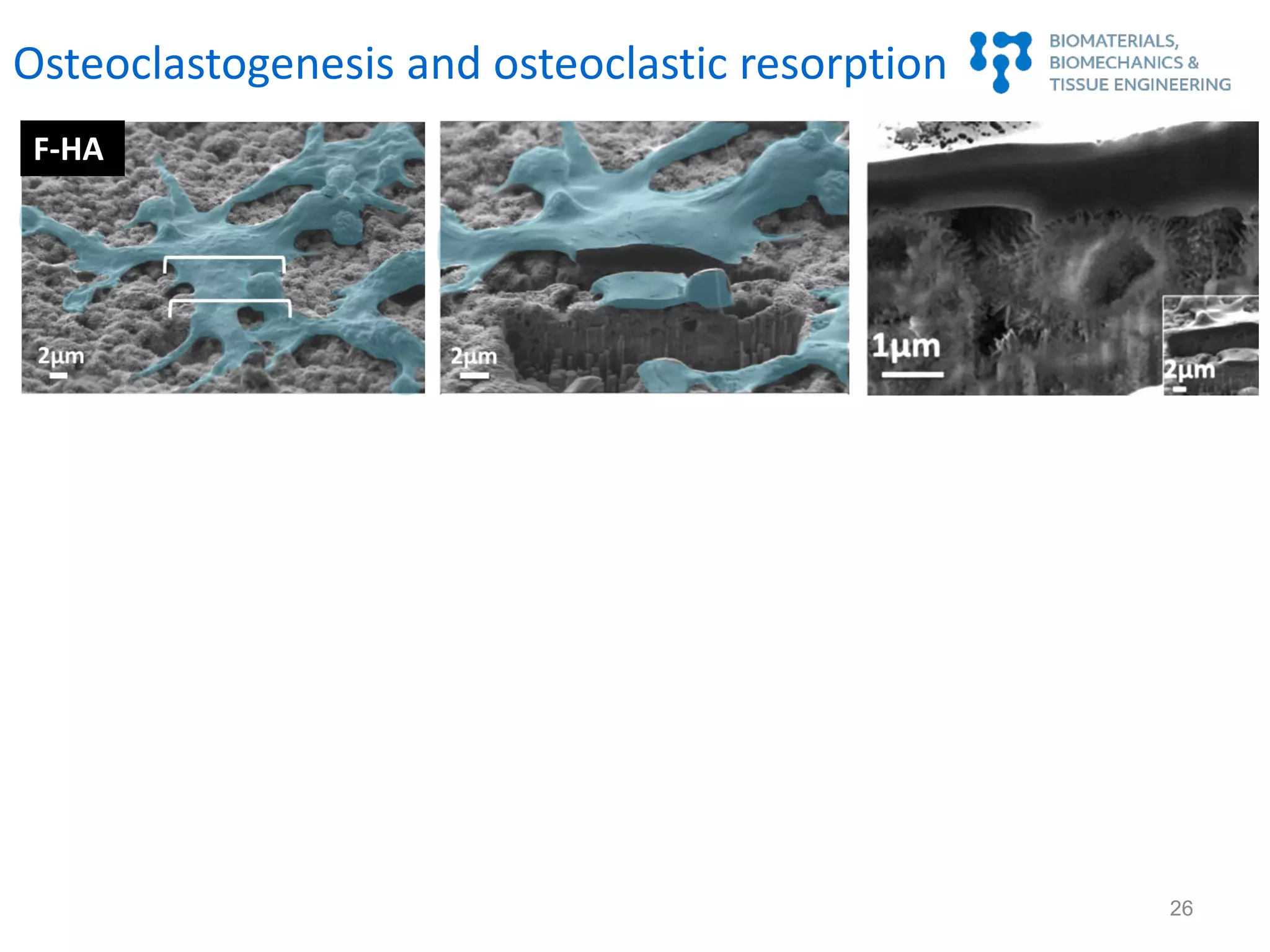

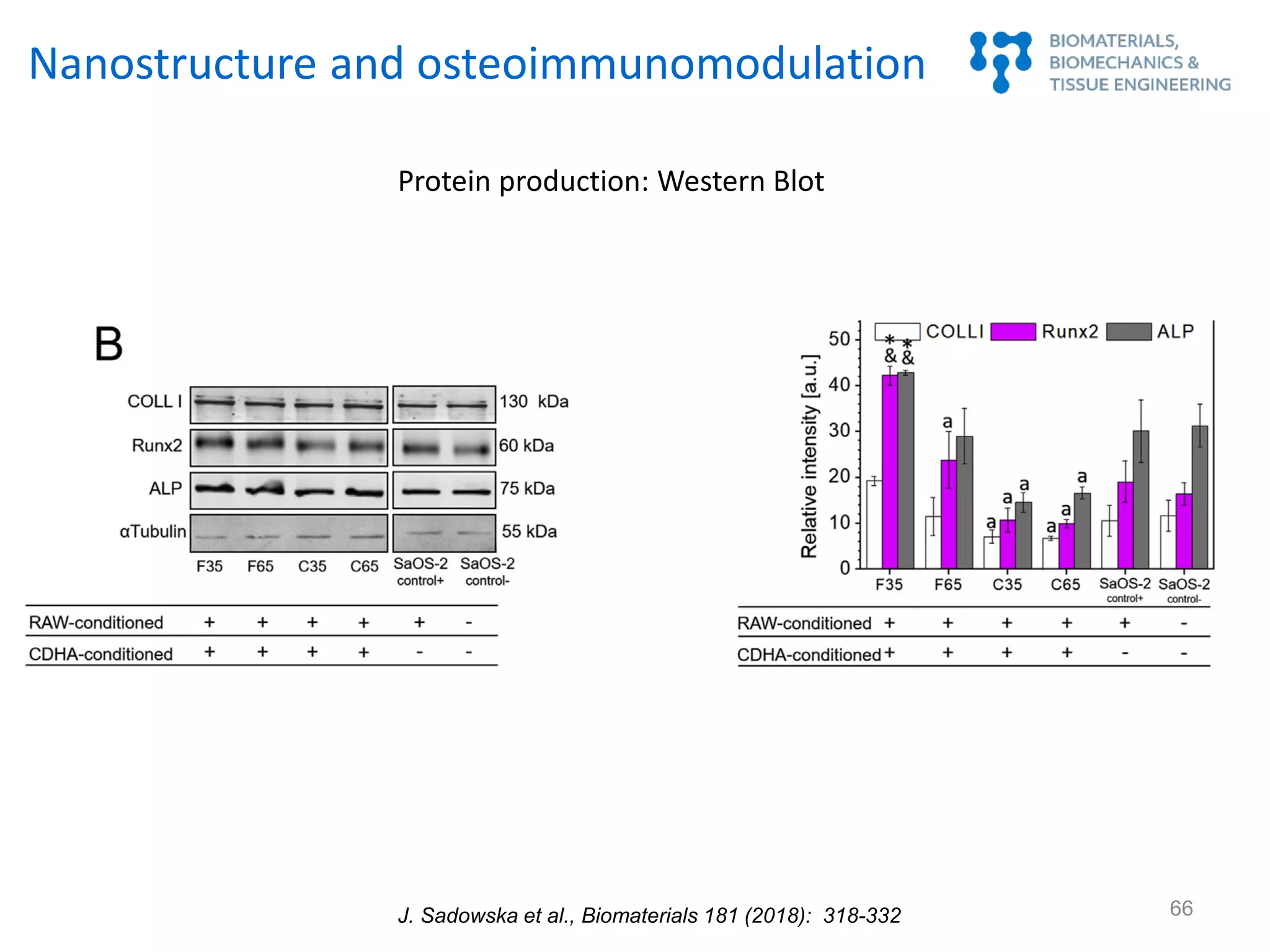

Nanostructure and osteoimmunomodulation

J. Sadowska et al., Biomaterials 181 (2018): 318-332

F35 F65 C35 C65 control

-10

0

10

20

30

40

50

ALParea/cellarea[%]

F35 F65 C65C35 SaOS-2 SaOS-2

control+ control-

a

a

b

a

b

*&

200 µm

ALP, F-actin, nuclei

67

Immunohistochemistry: ALP expression

J. Sadowska et al., Biomaterials (2018)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mariapauplenaria-191022131048/75/Bioinspired-strategies-for-bone-regeneration-67-2048.jpg)