1. Chylothorax is defined as a collection of chyle in the pleural cavity resulting from a leak in the lymphatic vessels, usually from the thoracic duct which transports lymph from the body.

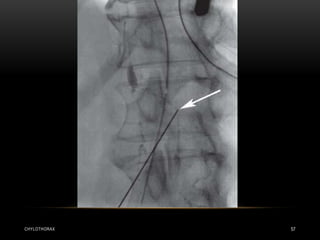

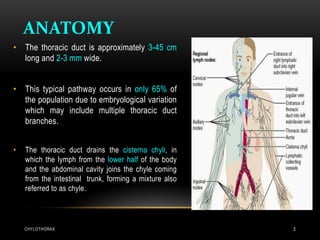

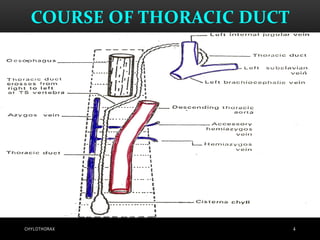

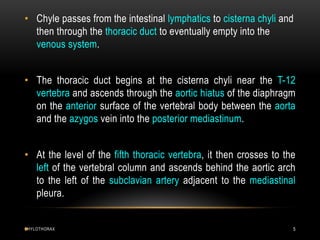

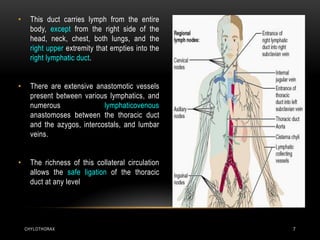

2. The thoracic duct anatomy is described, beginning near the kidneys and ascending through the diaphragm before crossing left and terminating near the subclavian vein. Damage to different parts of the duct can cause right or left-sided chylothorax.

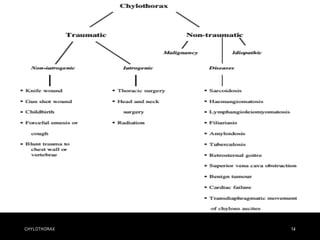

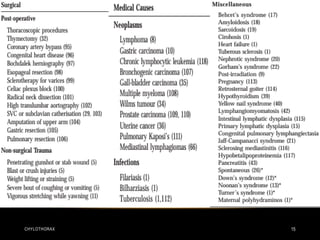

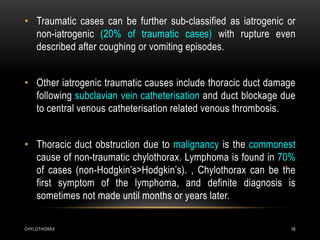

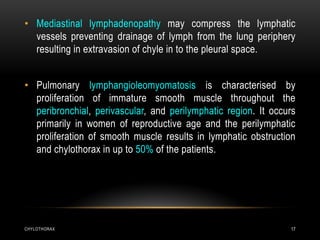

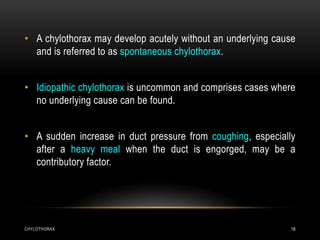

3. Causes of chylothorax include traumatic injury, malignancy compressing vessels, and spontaneous/idiopathic cases. Diagnosis involves fluid analysis showing chylomicrons.

![CHYLOTHORAX 30

• Chyle is also alkaline with a specific gravity of greater than 1.012 and will

settle on standing with a fat-rich portion on the top and a cellular sediment on

the bottom.

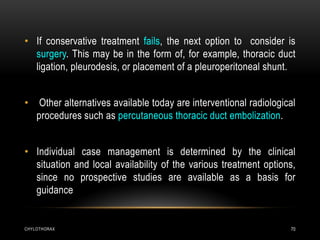

• In cases where the triglyceride level is above the criteria set for

pseudochylothorax but below those for chylothorax (55-110 mg/dl),

lipoprotein analysis is required to confirm or exclude a diagnosis of

chylothorax.

• A fluid to serum cholesterol ratio<1 and triglyceride ratio>1 are also found in

chylothorax.

• Most cases of chylothorax are exudative (high protein, low lactate

dehydrogenase [LDH]), but in about 25% of cases it can be transudative.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chylothorax-150724091554-lva1-app6892/85/Chylothorax-and-chyloptysis-30-320.jpg)