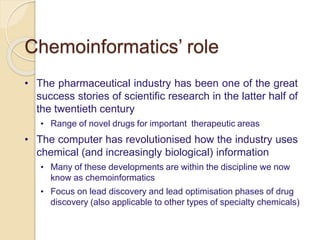

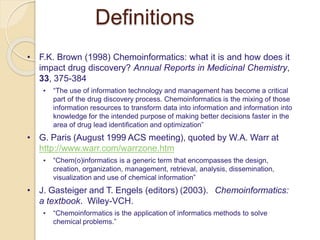

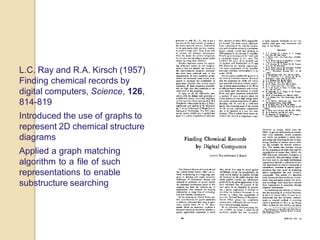

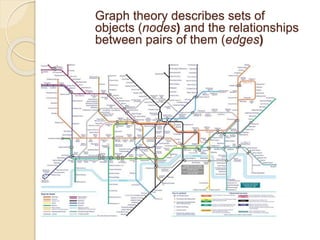

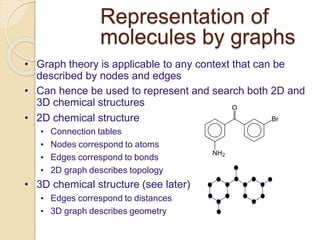

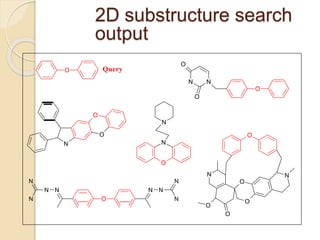

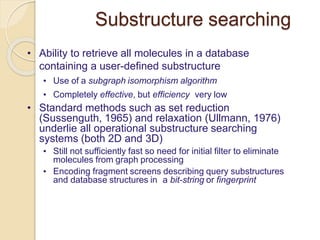

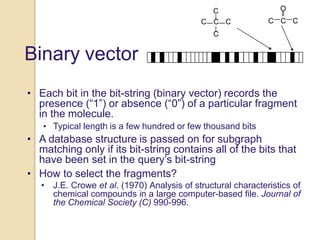

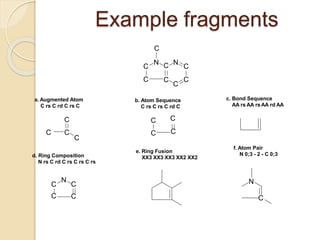

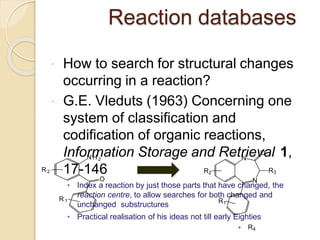

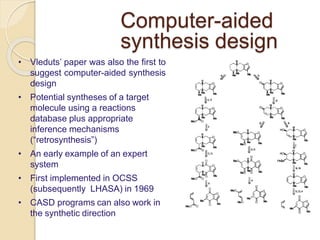

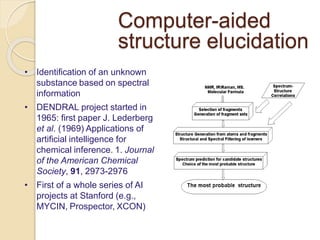

Chemoinformatics has developed over the past 50+ years to help analyze and utilize the large amount of chemical and biological data generated in drug discovery. Early work in the 1960s involved representing molecules as graphs to enable substructure searching of chemical databases. Key developments included the establishment of chemical literature databases and journals, as well as early computer systems for searching chemical structures and reactions. Methods from fields like artificial intelligence were also applied to problems like structure elucidation. Overall, chemoinformatics aims to transform chemical data into knowledge to help make better, faster decisions in drug lead identification and optimization.