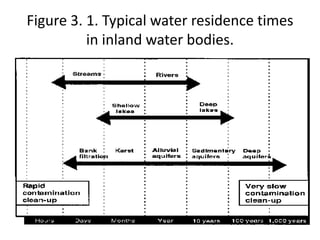

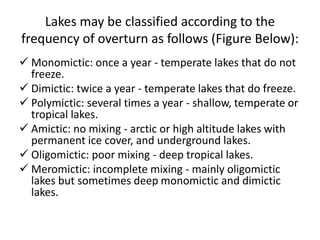

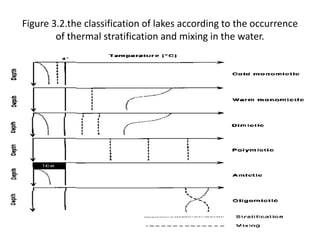

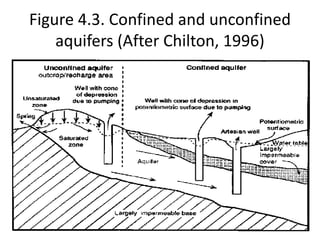

This document provides an overview of the biosphere. It defines the biosphere as comprising the parts of Earth where life exists, including the atmosphere, hydrosphere, lithosphere, and pedosphere. It discusses the components that make up the biosphere, including the lithosphere, hydrosphere, and groundwater. It also describes different types of lakes and aquifers, and factors that influence stratification and mixing in bodies of water.