- Engineering hydrology deals with applying hydrological principles to engineering projects involving water. It is used in designing structures like dams and bridges, as well as projects related to water supply, irrigation, flood control, and more.

- The hydrologic cycle describes the continuous movement of water on, above, and below the surface of the Earth. It involves processes like evaporation, transpiration, precipitation, runoff, percolation, and subsurface flow.

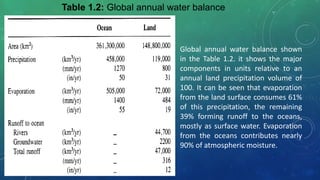

- Only a small fraction of the Earth's total water is fresh water available for human use. The majority is ocean water. Fresh water is stored in ice caps, groundwater, lakes, rivers, and the atmosphere.