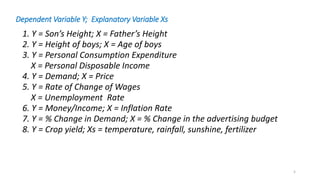

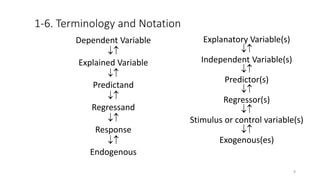

1) Regression analysis examines the relationship between a dependent variable and one or more independent variables. It was first developed by Francis Galton to study inheritance of traits.

2) Galton observed that the heights of children tended to "regress" toward the average height in the population, rather than matching their parents' exact heights. This was called "regression to mediocrity".

3) Simple linear regression analyzes the relationship between a single dependent variable and a single independent variable. It estimates the average value of the dependent variable based on the independent variable.