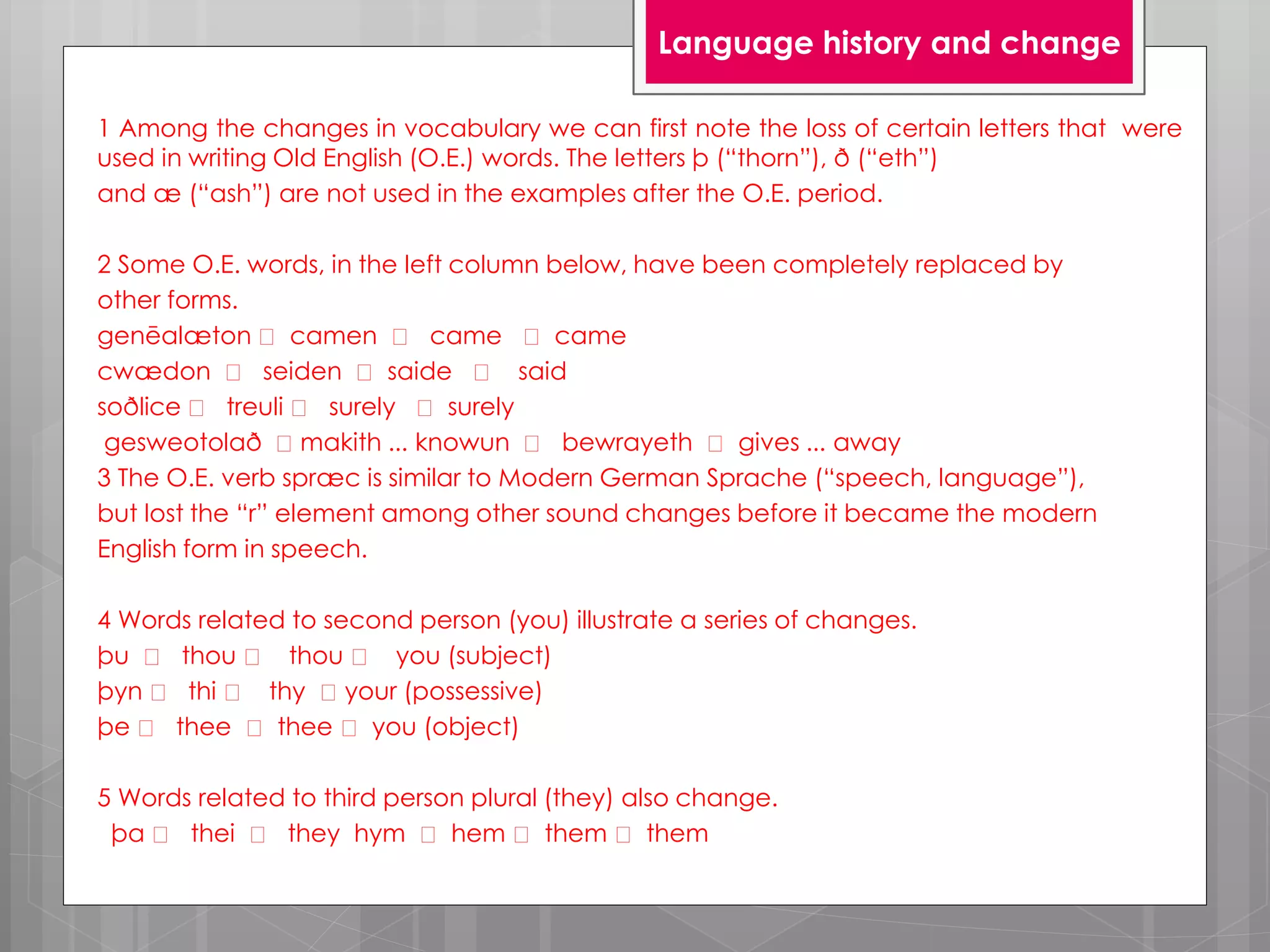

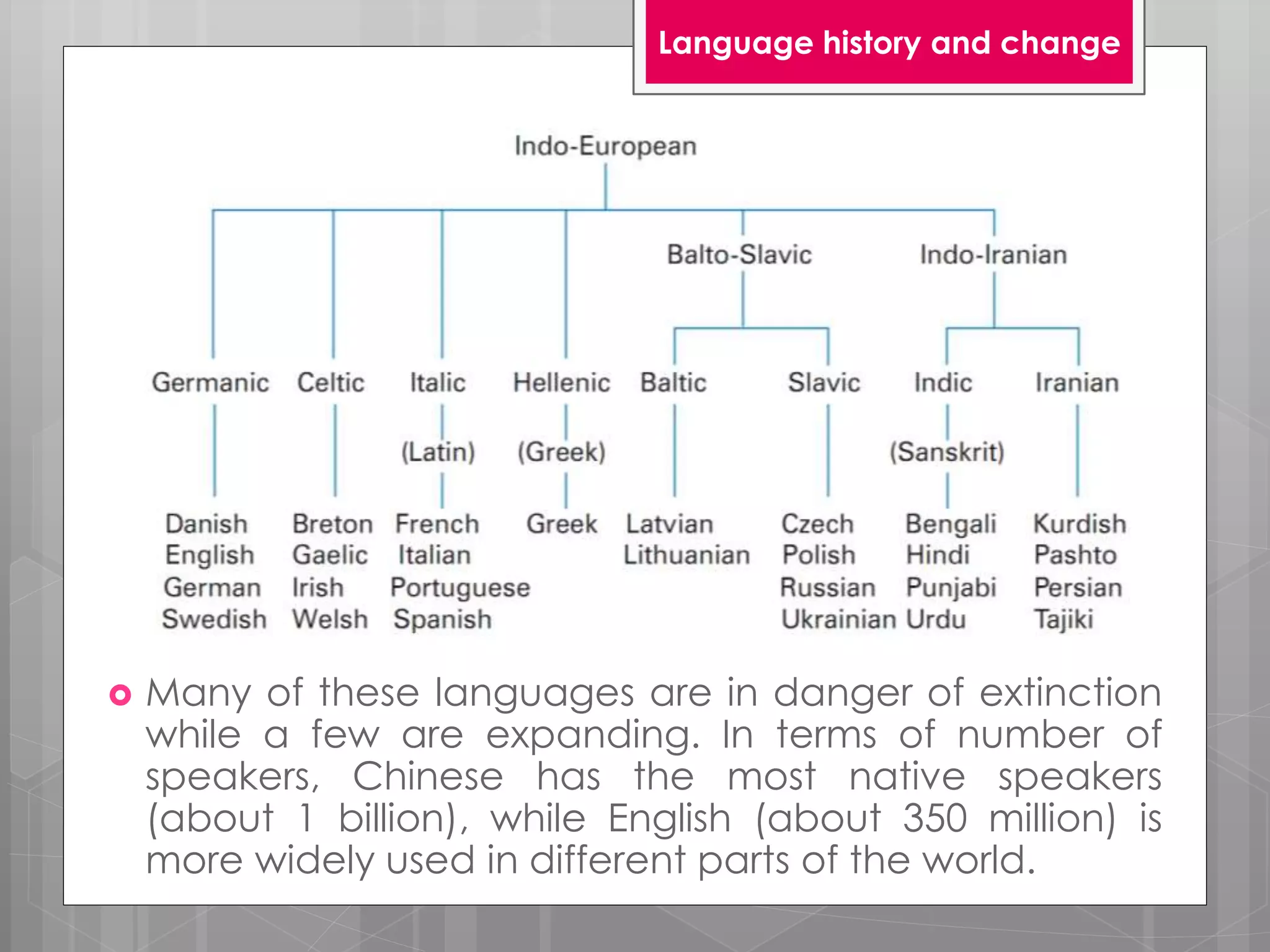

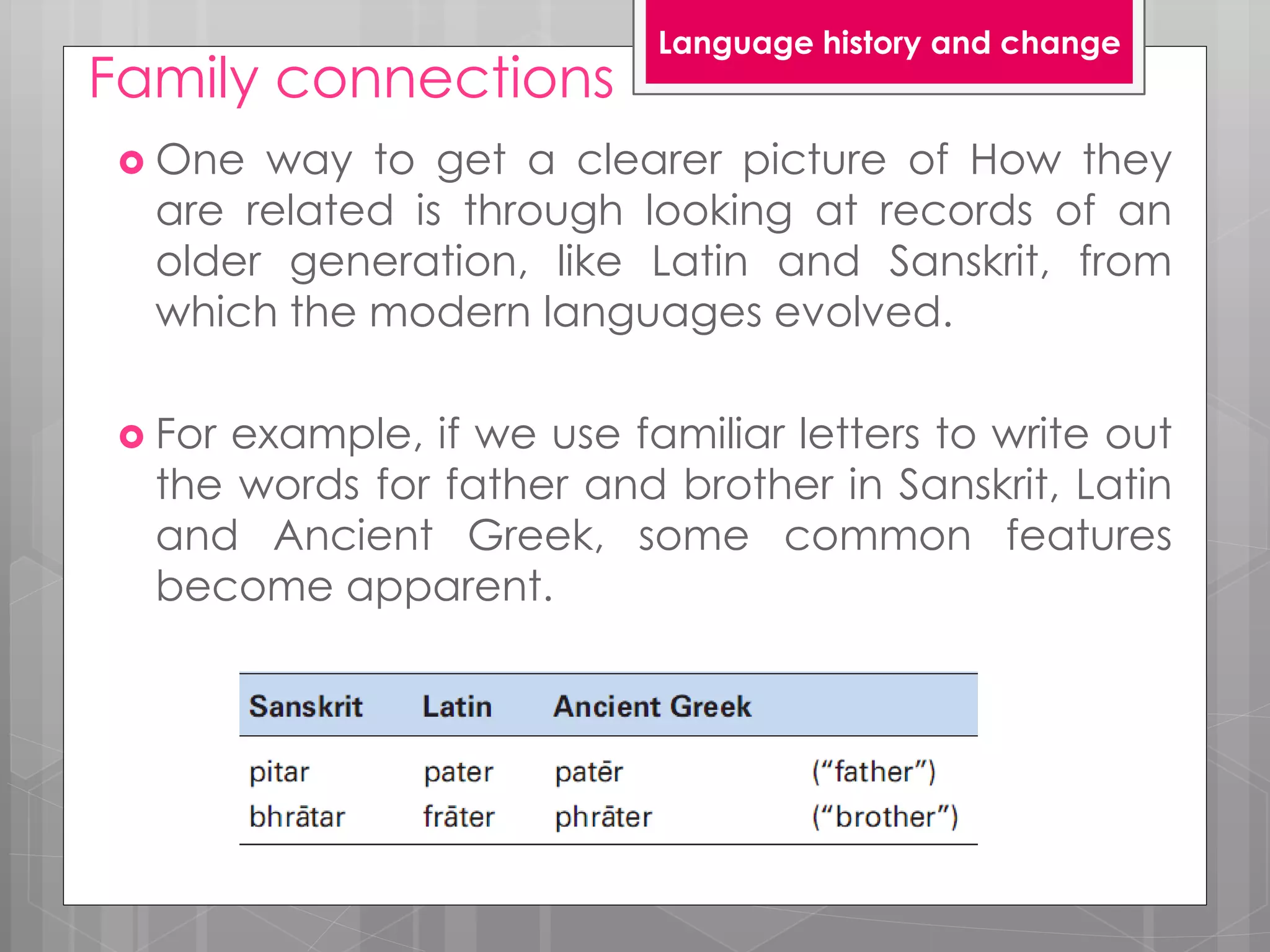

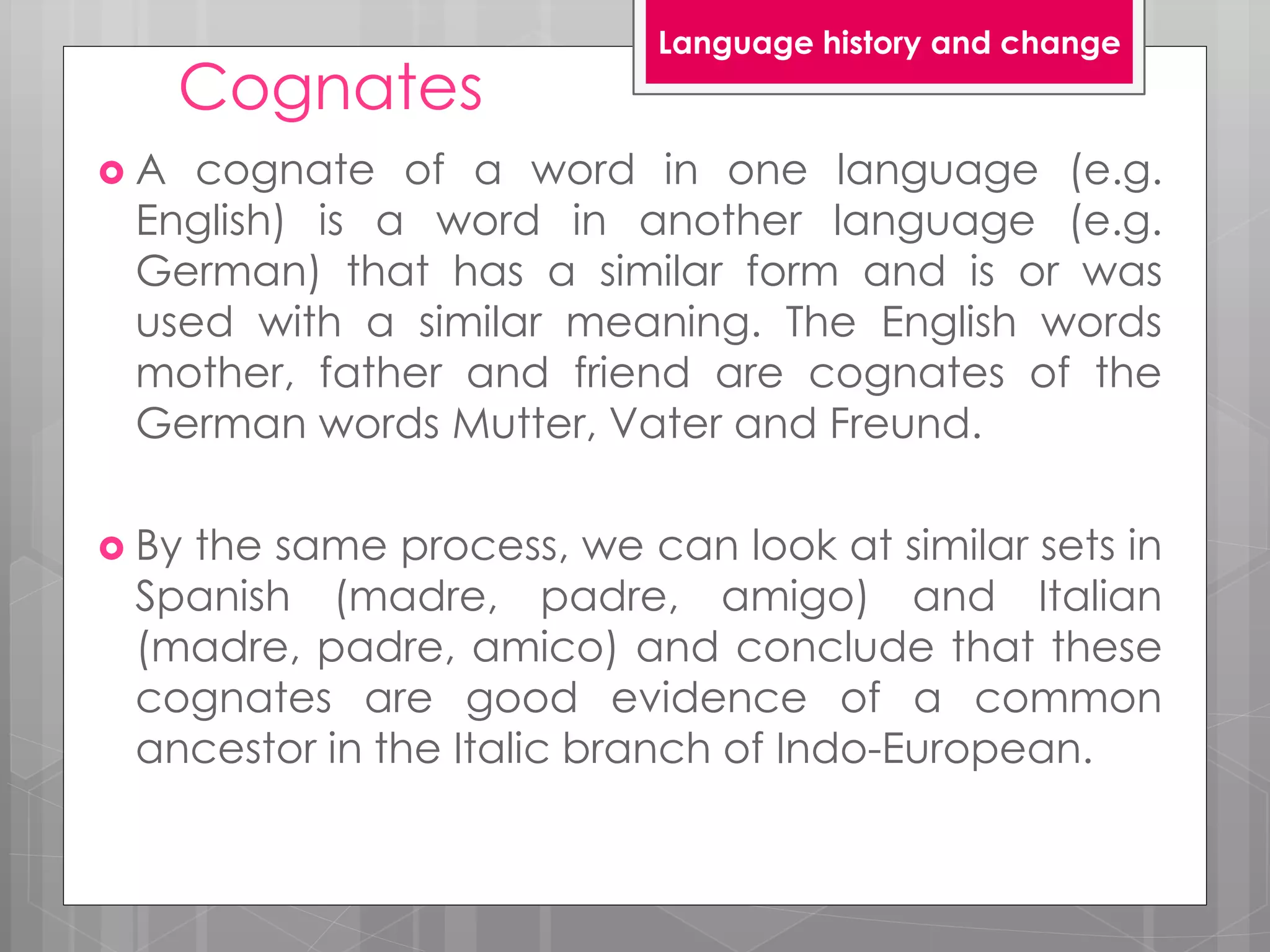

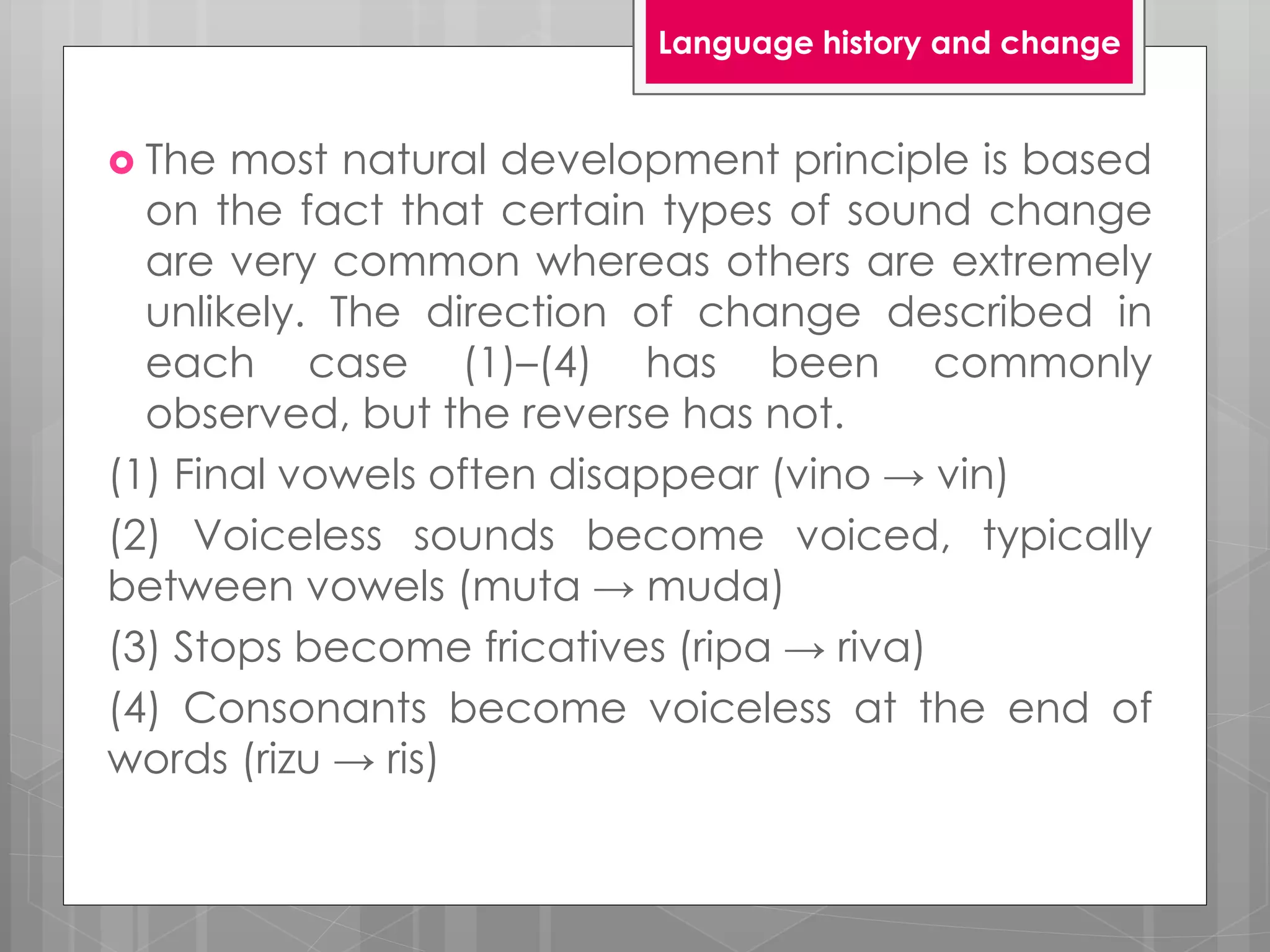

The document discusses the history and evolution of languages over time. It describes how Proto-Indo-European was identified as the common ancestor of many European and Indian languages based on similarities between their vocabularies and grammars. It also discusses methods of reconstructing earlier forms of words by comparing cognates across related languages and identifying common sound changes. As an example, it summarizes the major periods in the history of English from Old English to Modern English and some of the phonetic changes that occurred between each period like the loss of the letters þ and ð.

![Comparative

reconstruction

Using information from these sets of cognates, we

can embark on a procedure called comparative

reconstruction. The aim of this procedure is to

reconstruct what must have been the original or

“proto” form in the common ancestral language.

The majority principle is very straightforward. If, in a

cognate set, three words begin with a [p] sound

and one word begins with a [b] sound, then our

best guess is that the majority have retained the

original sound (i.e. [p]).

Language history and change](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter17languagehistoryandchange-150602053037-lva1-app6892/75/Chapter-17-language-history-and-change-7-2048.jpg)

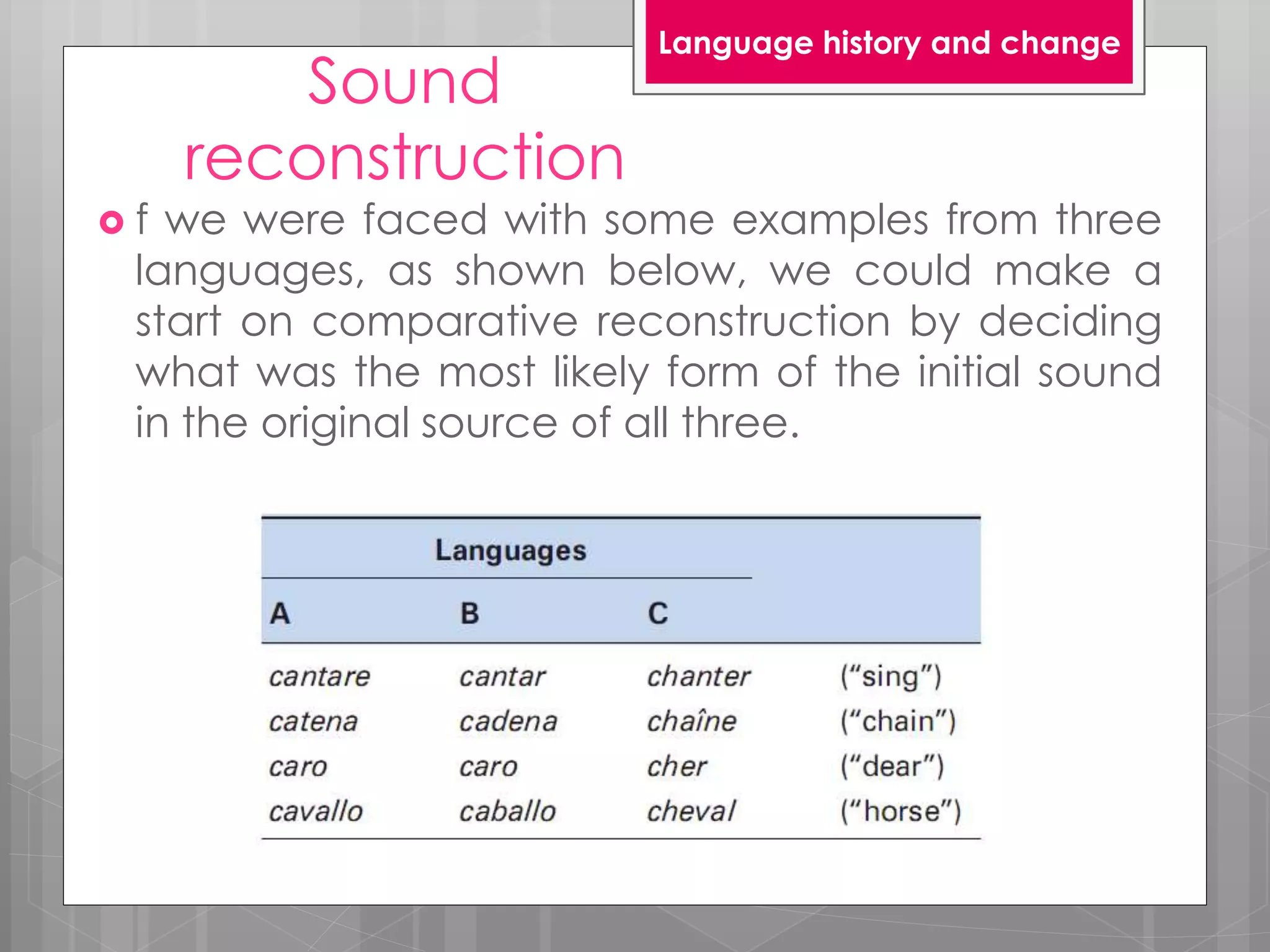

![ Since the written forms can often be misleading,

we check that the initial sounds of the words in

languages A and B are all [k] sounds, while in

language C the initial sounds are all [ʃ] sounds.

Through this type of procedure we have started

on the comparative reconstruction of the

common origins of some words in Italian (A),

Spanish (B) and French (C).

In this case, we have a way of checking our

reconstruction because the common origin for

these three languages is known to be Latin.

Language history and change](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter17languagehistoryandchange-150602053037-lva1-app6892/75/Chapter-17-language-history-and-change-10-2048.jpg)

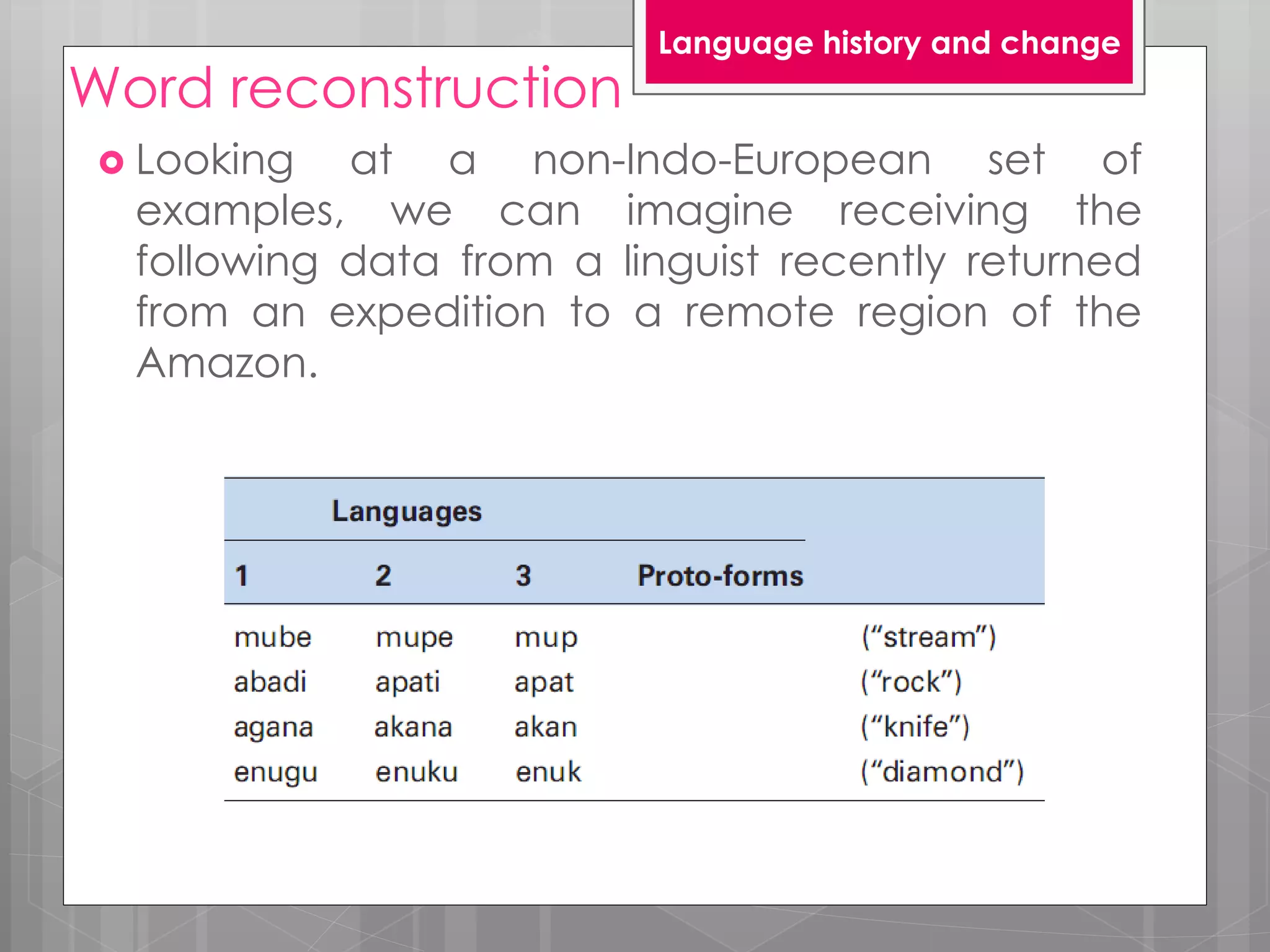

![ Using the majority principle, we can suggest that

the older forms will most likely be based on

language 2 or language 3. If this is correct, then

the consonant changes must have been [p] →

[b], [t] → [d] and [k] → [ɡ] in order to produce

the later forms in language 1. There is a pattern in

these changes that follows one part of the “most

natural development principle,” i.e. voiceless

sounds become voiced between vowels. So, the

words in languages 2 and 3 must be older forms

than those in language 1.

Language history and change](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter17languagehistoryandchange-150602053037-lva1-app6892/75/Chapter-17-language-history-and-change-12-2048.jpg)

![ he was cleped Madame Eglentyne Ful wel she

song the service dyvyne, Entuned in her nose ful

semely, And Frenche she spak ful faire and fetisly.

Most significantly, the vowel sounds of Chaucer’s

timewere very different fromthose we hear in

similar words today. Chaucer lived in what would

have sounded like a “hoos,” with his “weef,” and

“hay” might drink a bottle of “weena” with “heer”

by the light of the “mona.”

The effects of this general raising of long vowel

sounds (such as [oː] moving up to [uː], as in mo

¯na→moon) made the pronunciation of Early

Modern English, beginning around 1500,

significantly different from earlier periods.

Language history and change](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter17languagehistoryandchange-150602053037-lva1-app6892/75/Chapter-17-language-history-and-change-16-2048.jpg)

![Sound changes

sound loss: a sound change in which a particular

sound is no longer used in a language (e.g. the

velar fricative [x], in Scottish loch, but not in

Modern English).

The initial [h] of many Old English words was lost,

as in hlud → loud and hlaford →lord. Some words

lost sounds, but kept the spelling, resulting in the

“silent letters” of contemporary written English.

Another example is a velar fricative [x] that was

used in the older pronunciation of nicht as [nɪxt]

(closer to the Modern German pronunciation of

Nacht), but is absent in the contemporary

formnight, as [naɪt].

Language history and change](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter17languagehistoryandchange-150602053037-lva1-app6892/75/Chapter-17-language-history-and-change-17-2048.jpg)

![ The sound change known as metathesis involves a

reversal in position of two sounds in a word. This

type of reversal is illustrated in the changed

versions of these words from their earlier forms.

acsian → ask frist → first brinnan → beornan (burn)

bridd → bird hros → horse wæps → wasp

The reversal of position in metathesis can sometimes

occur between non-adjoinin sounds. The Spanish

word palabra is derived from the Latin parabola

through th reversal of the [l] and [r] sounds.

Language history and change](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter17languagehistoryandchange-150602053037-lva1-app6892/75/Chapter-17-language-history-and-change-18-2048.jpg)

![ Another type of sound change, known as

epenthesis, involves the addition of a sound to the

middle of a word.

æmtig → empty spinel → spindle timr → timber

The addition of a [p] sound after the nasal [m], as

in empty, can also be heard in some speakers’

pronunciation of something as “sumpthing.”

Language history and change](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter17languagehistoryandchange-150602053037-lva1-app6892/75/Chapter-17-language-history-and-change-19-2048.jpg)

![Syntactic changes

we find the Subject-Verb-Object order most

common in Modern English, but we can also find a

number of different orders that are no longer

used.

For example, the subject could follow the verb, as

in ferde he (“he traveled”), and the object could

be placed before the verb, as in he hine geseah

(“he saw him”), or at the beginning of the

sentence, as in him man ne sealde (“no man

gave [any] to him”).

and ne sealdest þu¯ me næfre a¯ n ticcen

and not gave you me never a kid

Language history and change](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter17languagehistoryandchange-150602053037-lva1-app6892/75/Chapter-17-language-history-and-change-21-2048.jpg)

![ 3 On the basis of the following data, what are the

most likely proto-forms?

Most likely proto-forms: cosa, capo, capra (initial [k],

voiceless [p] voiced [b])

Language history and change](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter17languagehistoryandchange-150602053037-lva1-app6892/75/Chapter-17-language-history-and-change-27-2048.jpg)

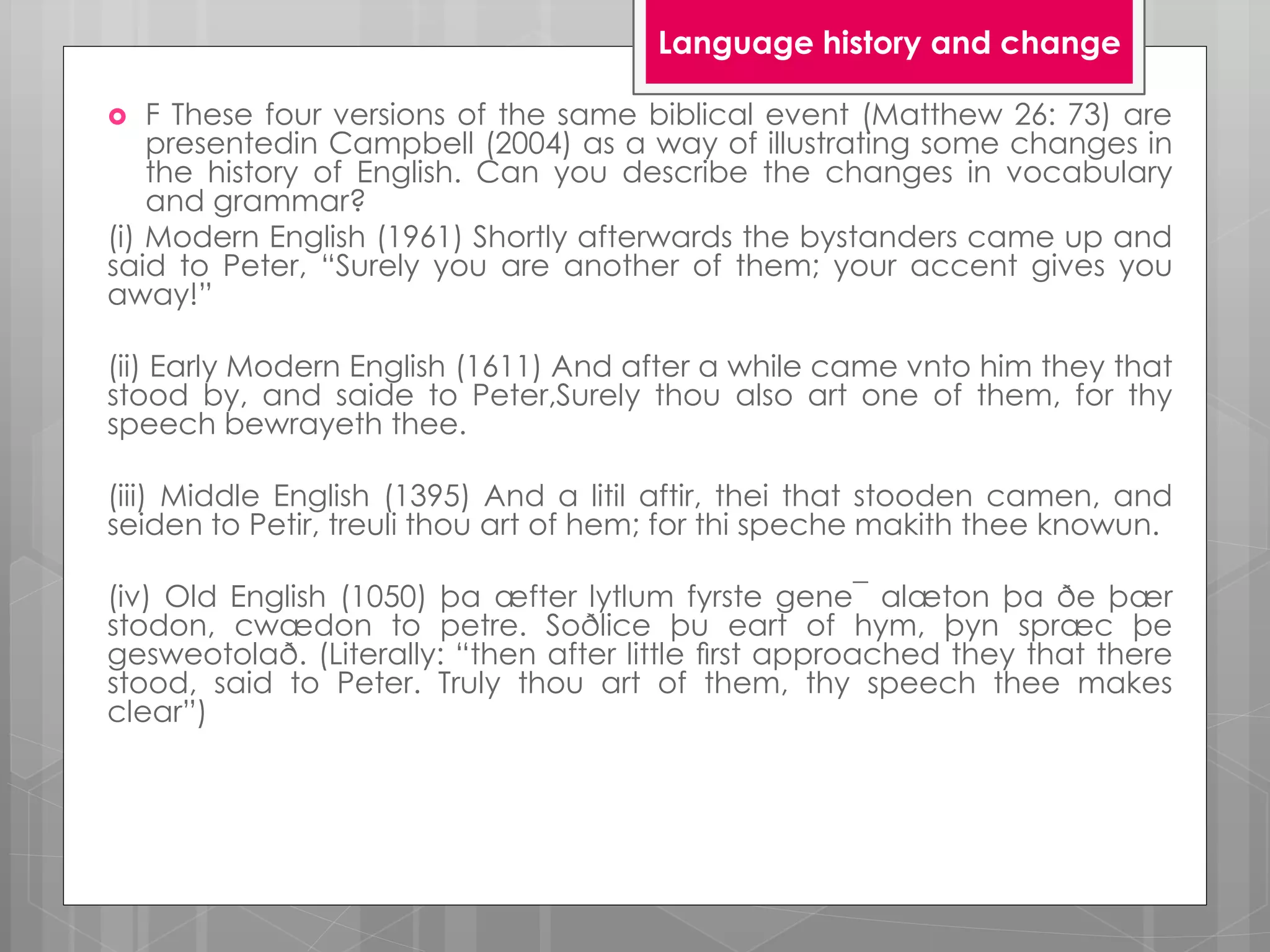

![ C A Danish linguist, Rasmus Rask, and a German writer more famous for fairy tales,

Jacob Grimm, both working in the early nineteenth century, are credited with the

original insights that became known as “Grimm’s Law.” What is Grimm’s Law and how

does it account for the different initial sounds in pairs of cognates such as these from

French and English (deux / two, trois / three) and these from Latin and English (pater /

father, canis / hound, genus / kin)?

Grimm’s Law

Indo-European consonants underwent a series of regular sound changes in the

development of the Germanic branch that did not happen in the Italic branch (and other

branches). As a descendant of the Germanic branch, English has a number of words that

show the results of the sound changes when compared to French and Latin words (both in

the Italic branch). Grimm’s Law is essentially a small set of rules that show how most of those

changes took place in a regular pattern. Voiceless stops such as [p], [t] and [k] became

voiceless fricatives [f], [θ] and [h] in the Germanic branch, but not in the Italic branch, as

illustrated by the pairs pater/father, tres/three and canis/hound. Voiced stops such as [d]

and [ɡ] became voiceless stops [t] and [k], as in the pairs duo/two and genus/kin. These

are examples of the regular patterns of change described by Grimm’s Law and can still be

found in the differences between first consonants of the French/English cognates deux/two

and trois/three. The basic set of changes is presented here, with Indo-European

consonants on the left and Germanic consonants on the right.

voiceless stops /p, t, k/ voiceless fricatives /f, θ, h/

voiced stops /b, d, g/ voiceless stops /p, t, k/

voiced aspirated stops /bh, dh, gh/ voiced stops /b, d, g/ The circular nature of these

sound change rules is considered to be a good feature.

Language history and change](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter17languagehistoryandchange-150602053037-lva1-app6892/75/Chapter-17-language-history-and-change-32-2048.jpg)