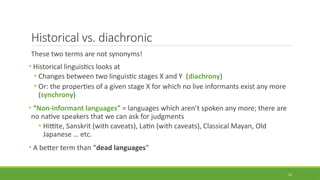

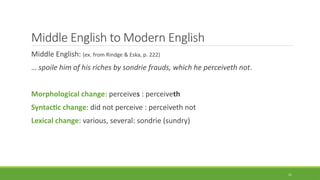

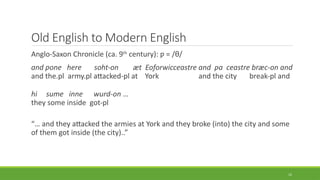

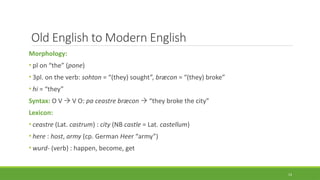

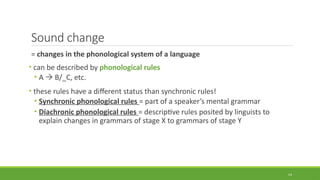

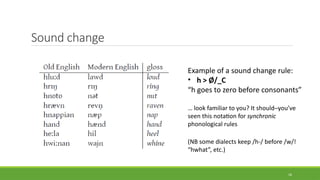

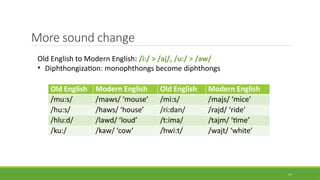

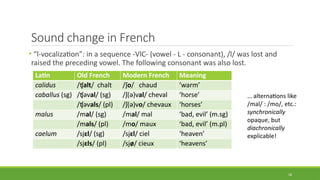

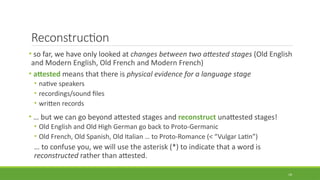

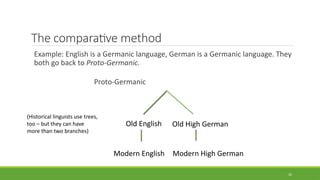

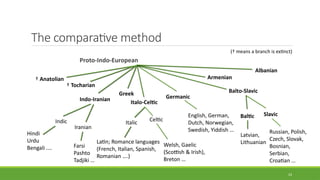

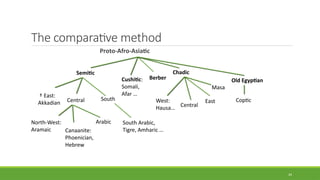

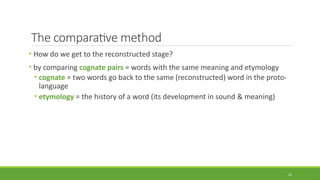

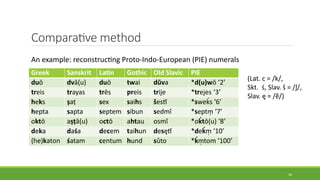

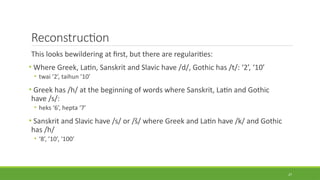

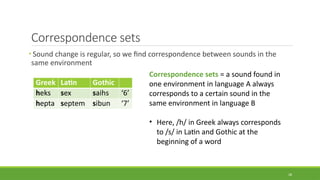

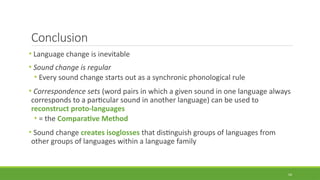

Historical linguistics studies language change over time by examining how languages have evolved from earlier stages to their modern forms. Languages are constantly changing in their phonology, morphology, syntax, and lexicon. Historical linguists use the comparative method and reconstruct ancestral proto-languages to show genetic relationships between languages and trace their development from a common ancestor. Sound changes from one language stage to another usually follow regular phonetic processes.