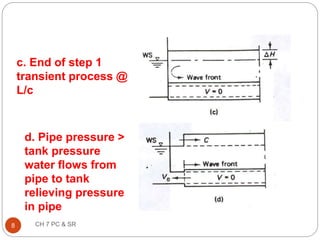

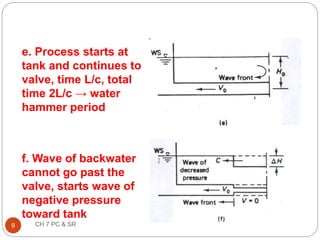

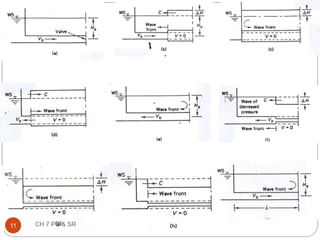

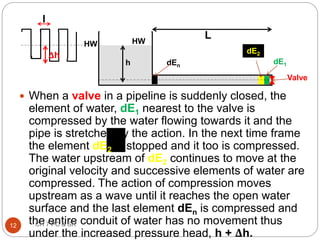

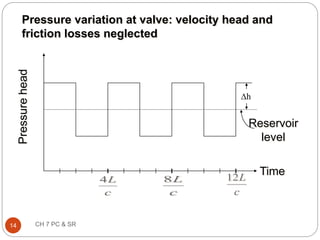

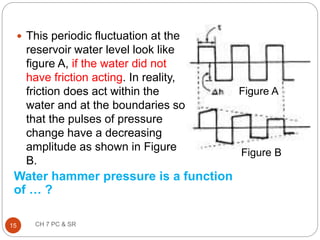

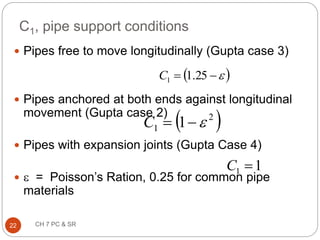

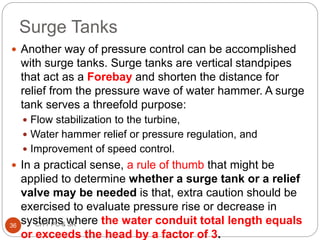

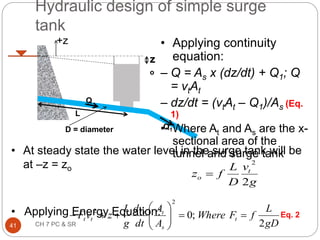

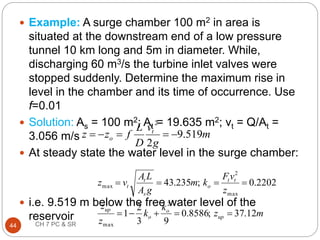

This document discusses pressure control and speed regulation in hydroelectric plants. It covers water hammer theory, which describes how rapid changes in water flow can cause pressure fluctuations that travel through pipes as waves. Proper pressure control requires an understanding of water hammer and the use of equipment like governors, pressure relief valves, and surge tanks. The document presents the elastic water column theory and rigid water column theory for analyzing water hammer. It defines key terms, shows how to calculate the speed of pressure waves, and determines the maximum pressure increase caused by water hammer. Maintaining steady turbine speed and pipe pressure requires systems that can regulate water flow during sudden changes.