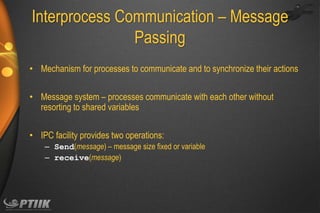

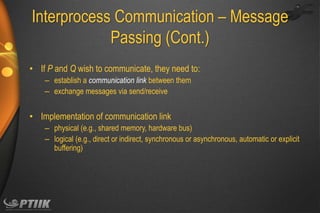

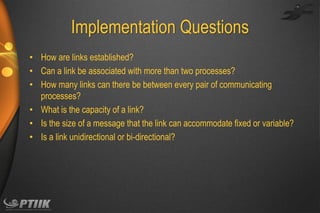

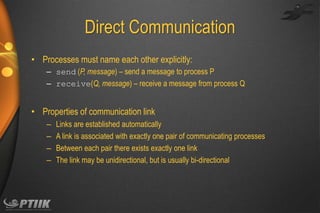

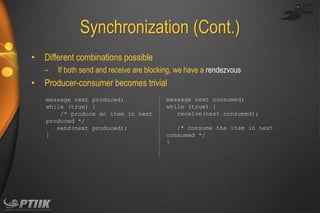

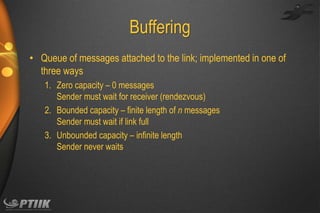

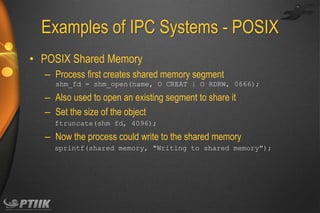

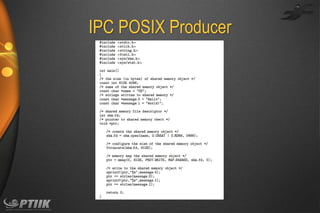

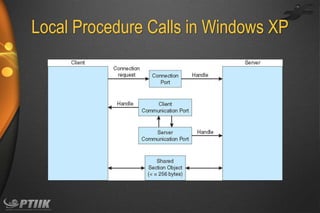

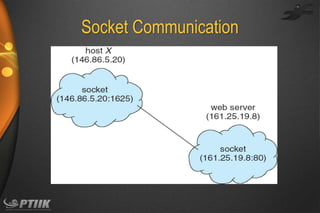

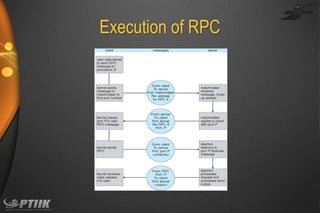

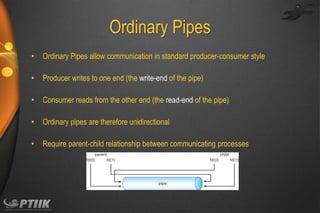

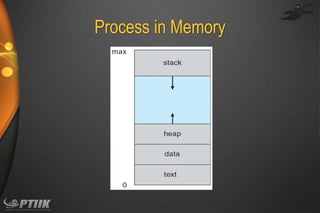

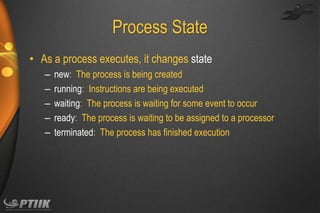

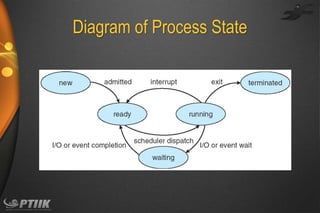

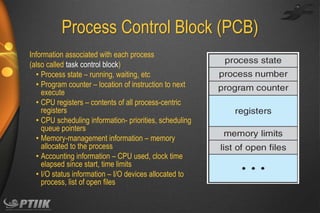

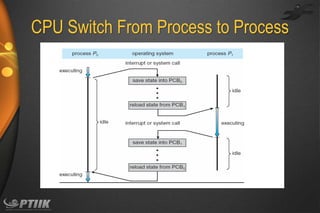

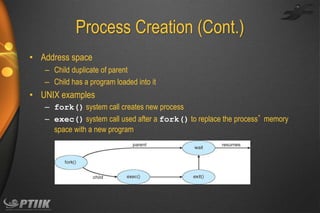

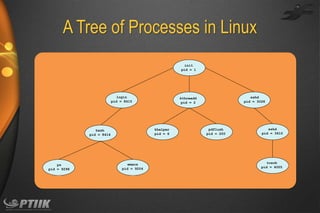

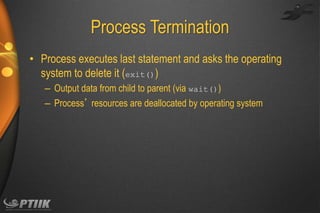

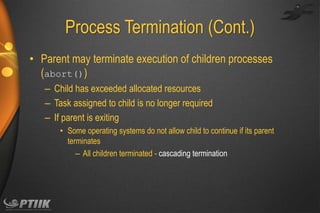

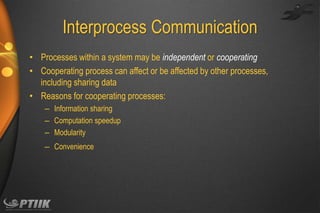

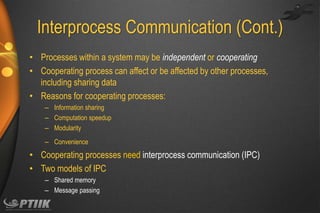

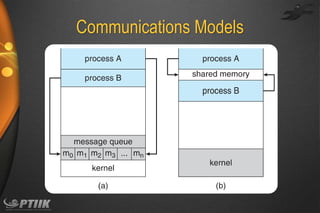

The document discusses processes and interprocess communication. It defines a process as a program in execution that forms the basis of computation. Processes have states like running, waiting, ready and terminated. A process is represented in memory and by a process control block. Processes communicate through shared memory or message passing. Examples of interprocess communication systems include POSIX shared memory, Mach message passing and Windows local procedure calls. Communication in client-server systems uses sockets, remote procedure calls and pipes.

![Bounded-Buffer – Shared-Memory Solution

• Shared data

#define BUFFER_SIZE 10

typedef struct {

. . .

} item;

item buffer[BUFFER_SIZE];

int in = 0;

int out = 0;

• Solution is correct, but can only use BUFFER_SIZE-1 elements](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ch3-processes-140116113231-phpapp02/85/Ch3-processes-38-320.jpg)

![Bounded Buffer – Consumer

item next consumed;

while (true) {

while (in == out)

; /* do nothing */

next consumed = buffer[out];

out = (out + 1) % BUFFER SIZE;

/* consume the item in next consumed */

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ch3-processes-140116113231-phpapp02/85/Ch3-processes-39-320.jpg)