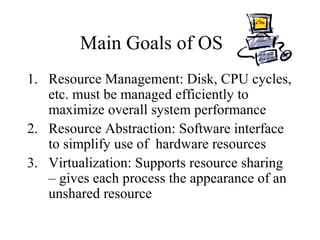

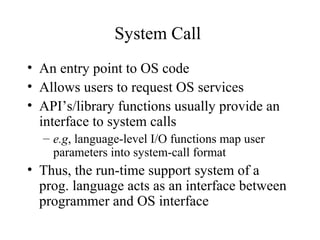

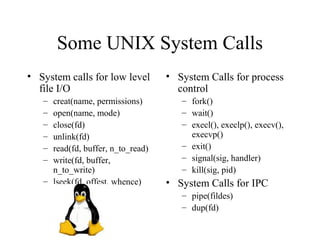

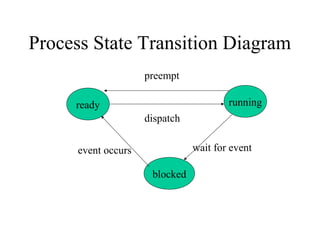

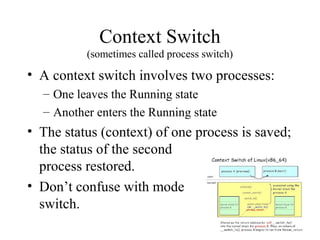

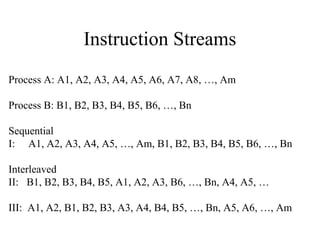

The document discusses basic operating system concepts including resource management, abstraction, and virtualization as main goals of an OS. It describes system calls as entry points for users to request OS services, and some common UNIX system calls. It also reviews key OS concepts like processes, threads, scheduling, synchronization, and memory management.