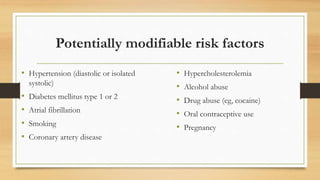

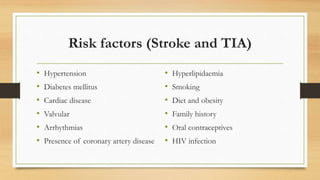

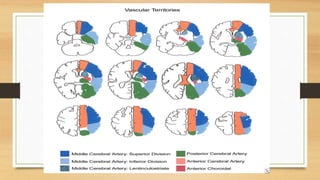

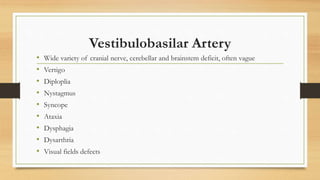

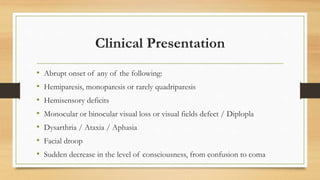

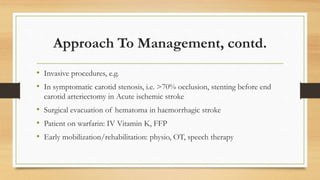

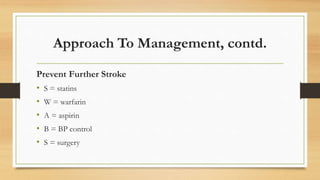

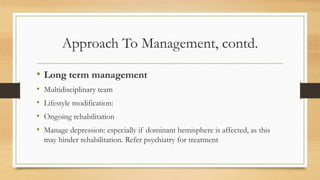

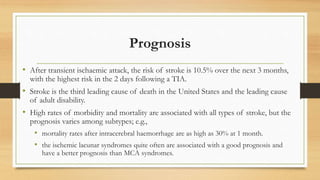

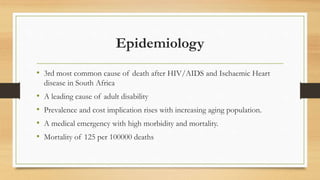

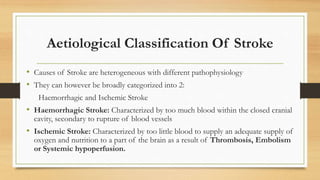

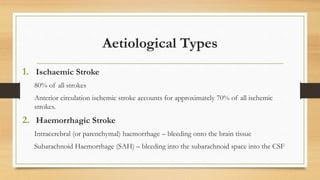

This document provides an overview of the approach to managing cerebrovascular accidents (CVAs), also known as strokes. It begins with definitions, epidemiology, and risk factors. It then discusses the clinical presentation and neurological deficits associated with different blood vessels. Common complications are also reviewed. The approach to initial management focuses on resuscitation, history and examination, investigations, and acute treatment including medications, monitoring, and prevention of secondary complications. Long-term management involves rehabilitation, lifestyle modifications, and managing risk factors to prevent further strokes. Prognosis varies depending on the stroke subtype but overall many patients experience disability or death.

![Risk factors: Non-Modifiable

• Age (risk rises exponentially with age)

• Sex (more common in males at all ages)

• Race (African American > Asian > Caucasian)

• Geography (Eastern Europe > Western Europe > Asia > rest of Europe or

North America)

• Genetic risk factors (eg stroke or heart disease in individuals younger than 60

yr; familial syndromes, such as cerebral autosomal arteriopathy [CADASIL]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cerebrovascularaccidentoct-2017-171001192204/85/Cerebrovascular-accident-oct-2017-9-320.jpg)