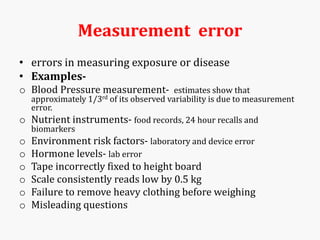

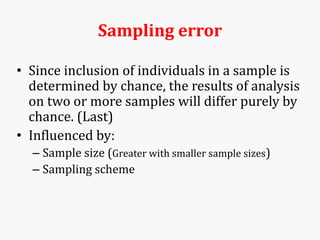

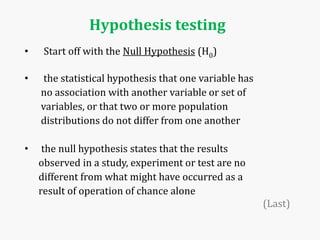

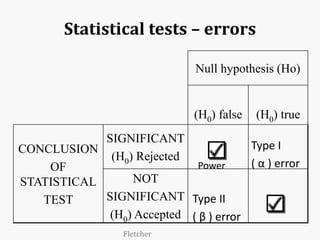

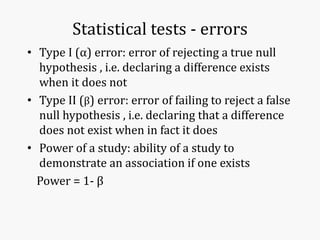

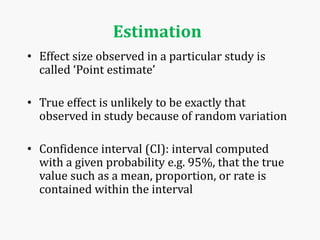

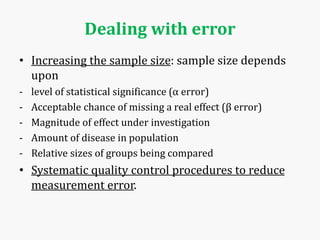

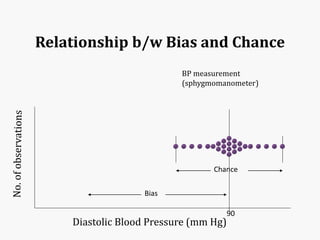

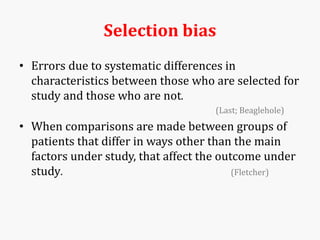

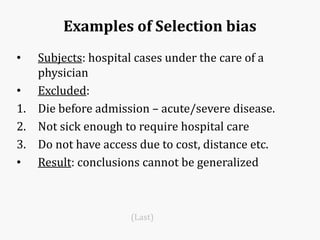

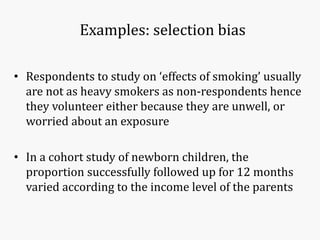

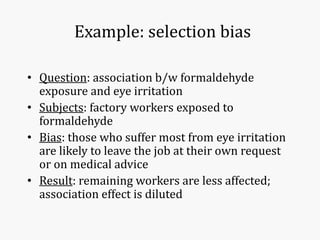

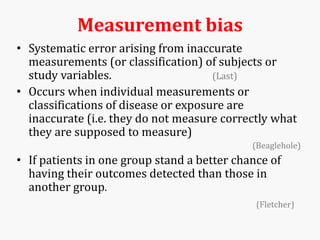

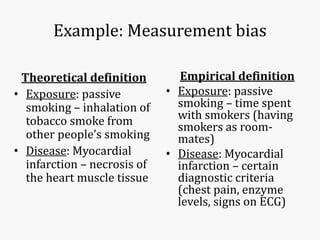

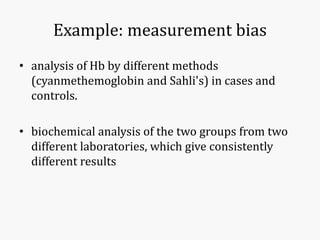

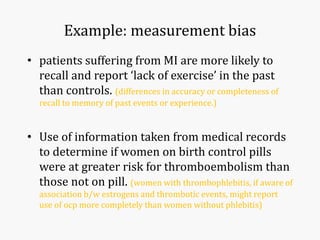

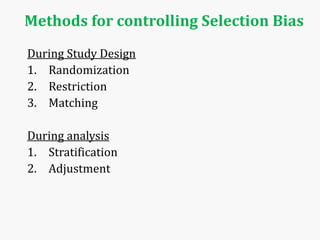

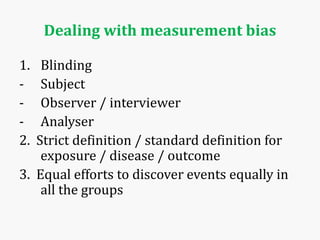

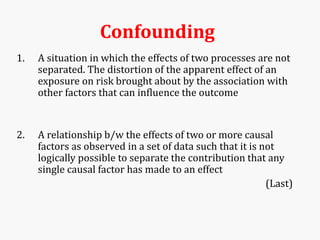

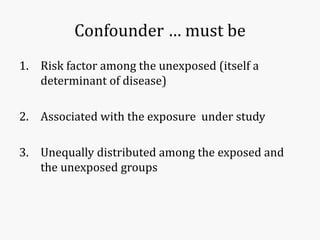

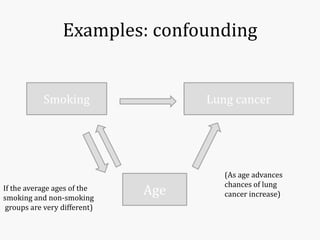

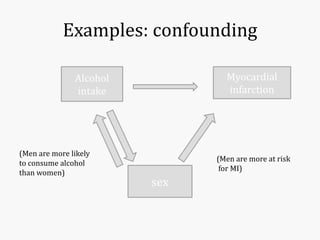

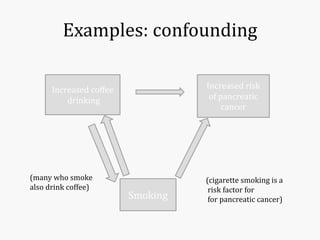

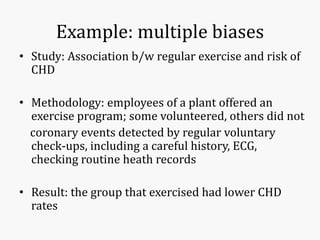

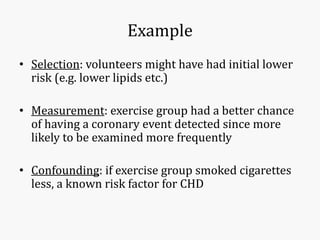

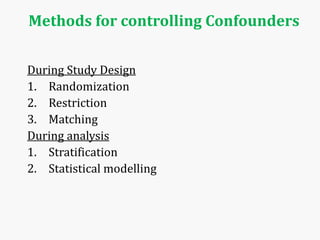

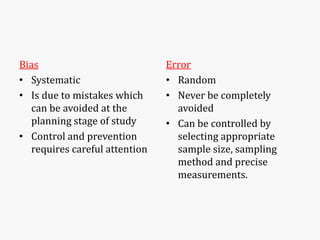

Systematic and random errors can affect epidemiological studies. Random errors are due to chance and include individual biological variation, measurement error, and sampling error. Systematic errors, also called biases, are non-random and can distort study results. Selection bias occurs if study groups differ in characteristics unrelated to exposure that influence outcomes. Measurement bias happens if exposures or diseases are inaccurately classified. Confounding is present when a third factor is associated with both the exposure and outcome under investigation. Careful study design and analysis techniques can help reduce biases and errors to obtain more accurate results.