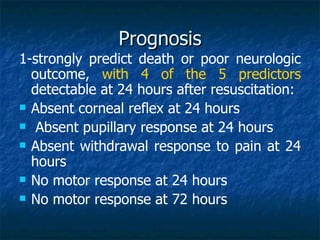

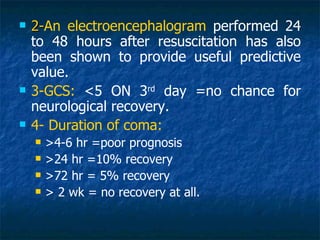

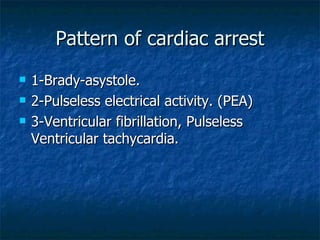

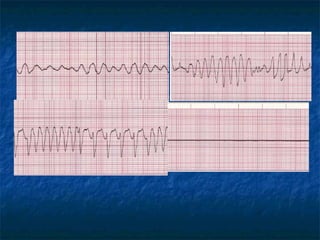

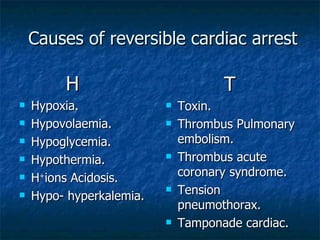

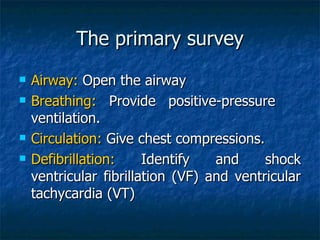

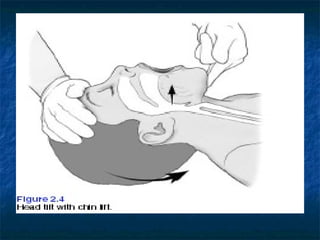

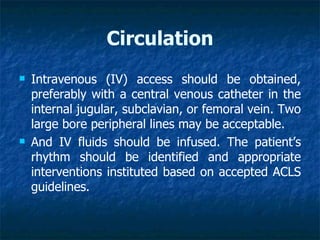

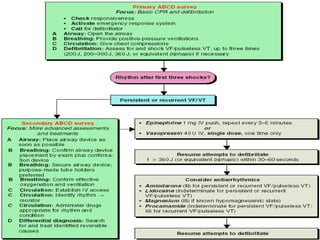

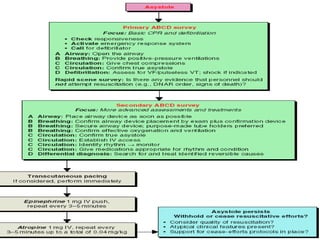

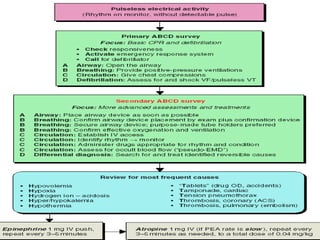

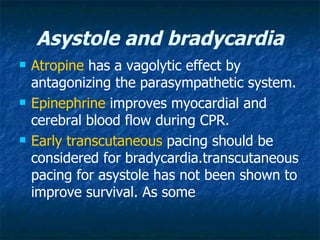

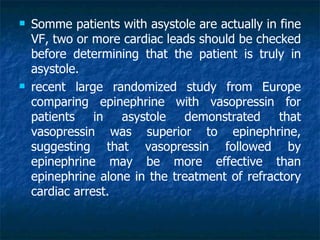

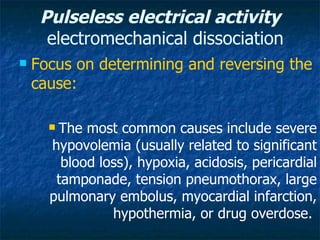

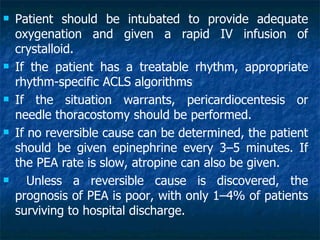

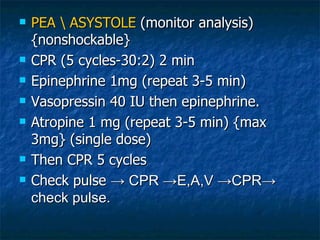

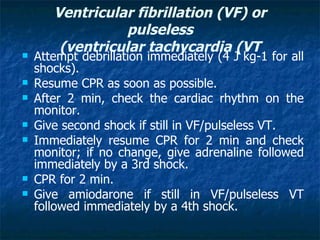

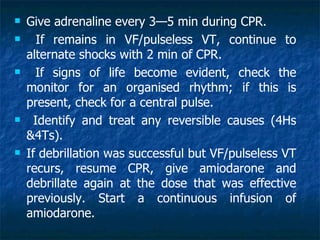

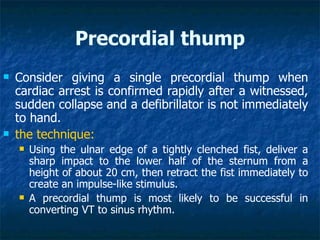

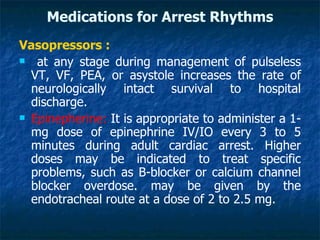

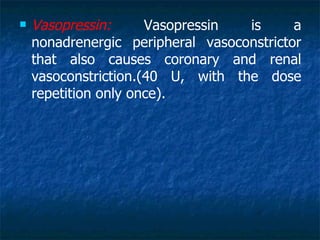

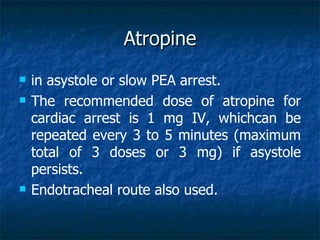

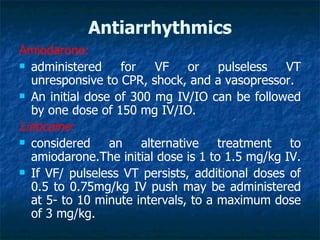

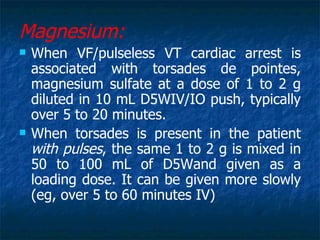

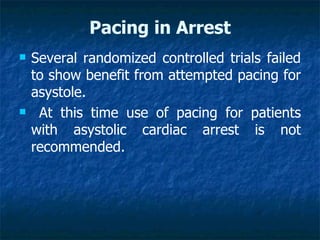

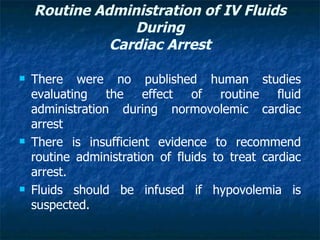

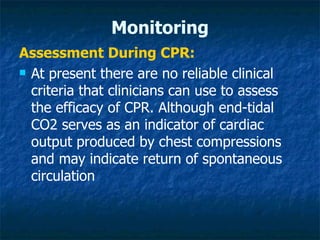

This document provides information on cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) including the patterns of cardiac arrest, causes of reversible cardiac arrest, the primary and secondary surveys of CPR, and treatments for different cardiac rhythms encountered during resuscitation such as asystole, bradycardia, and pulseless electrical activity. It details the steps for opening the airway, providing ventilation, performing chest compressions, and defibrillation. It also outlines advanced life support interventions including intubation, intravenous access, defibrillation, and medications for specific rhythms.

![Assessment of Hemodynamics

1-Coronary Perfusion Pressure

(CPP= aortic relaxation [diastolic] pressure

minus right atrial relaxation phase blood

pressure)

during CPR correlates with both myocardial

blood flow and ROSC.

A CPP of 15 mm Hg is predictive of ROSC.

Increased CPP correlate with improved 24-hour

survival rates in animal studies.

Rarely available](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cardiacarrest-120316132422-phpapp02/85/Cardiac-arrest-49-320.jpg)