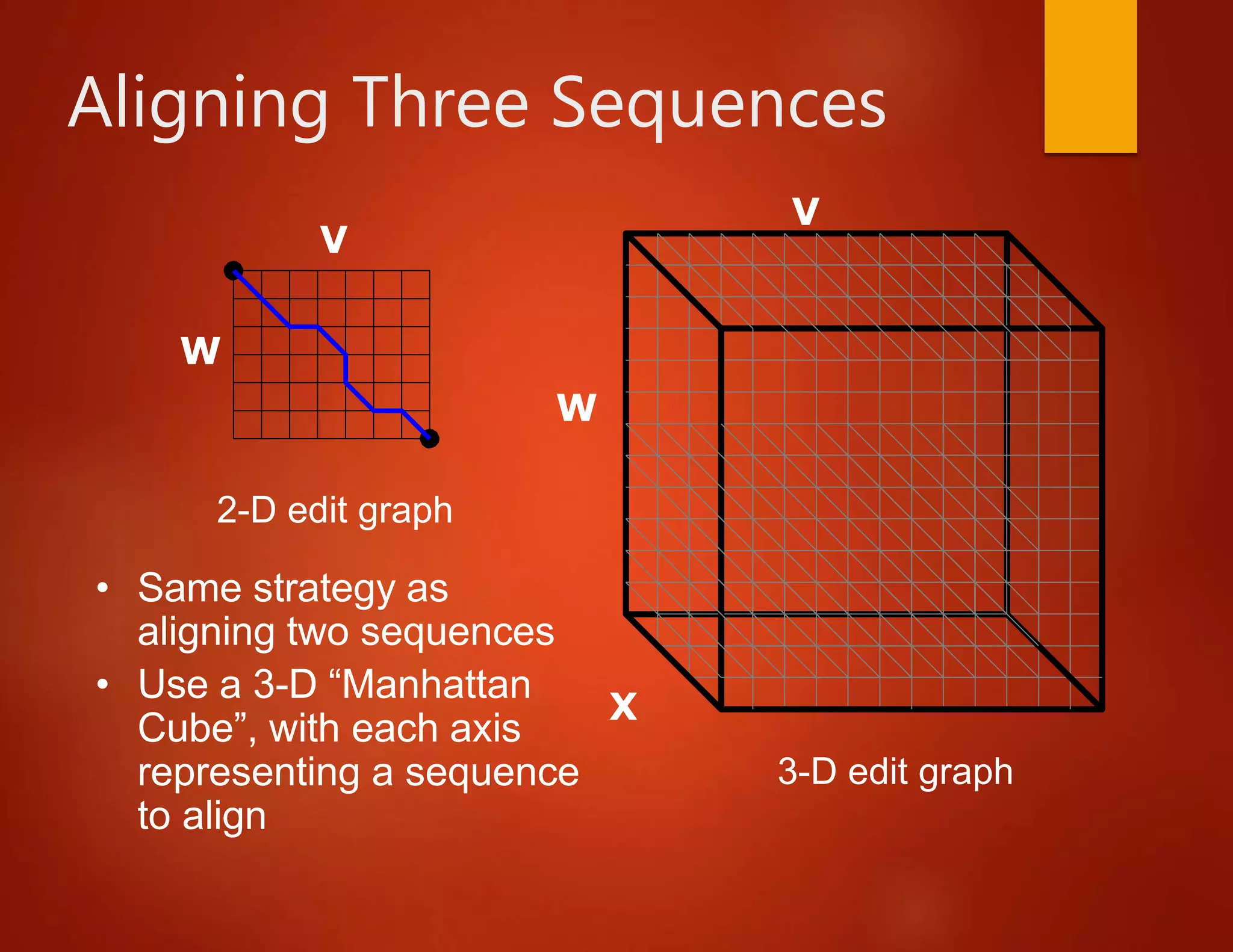

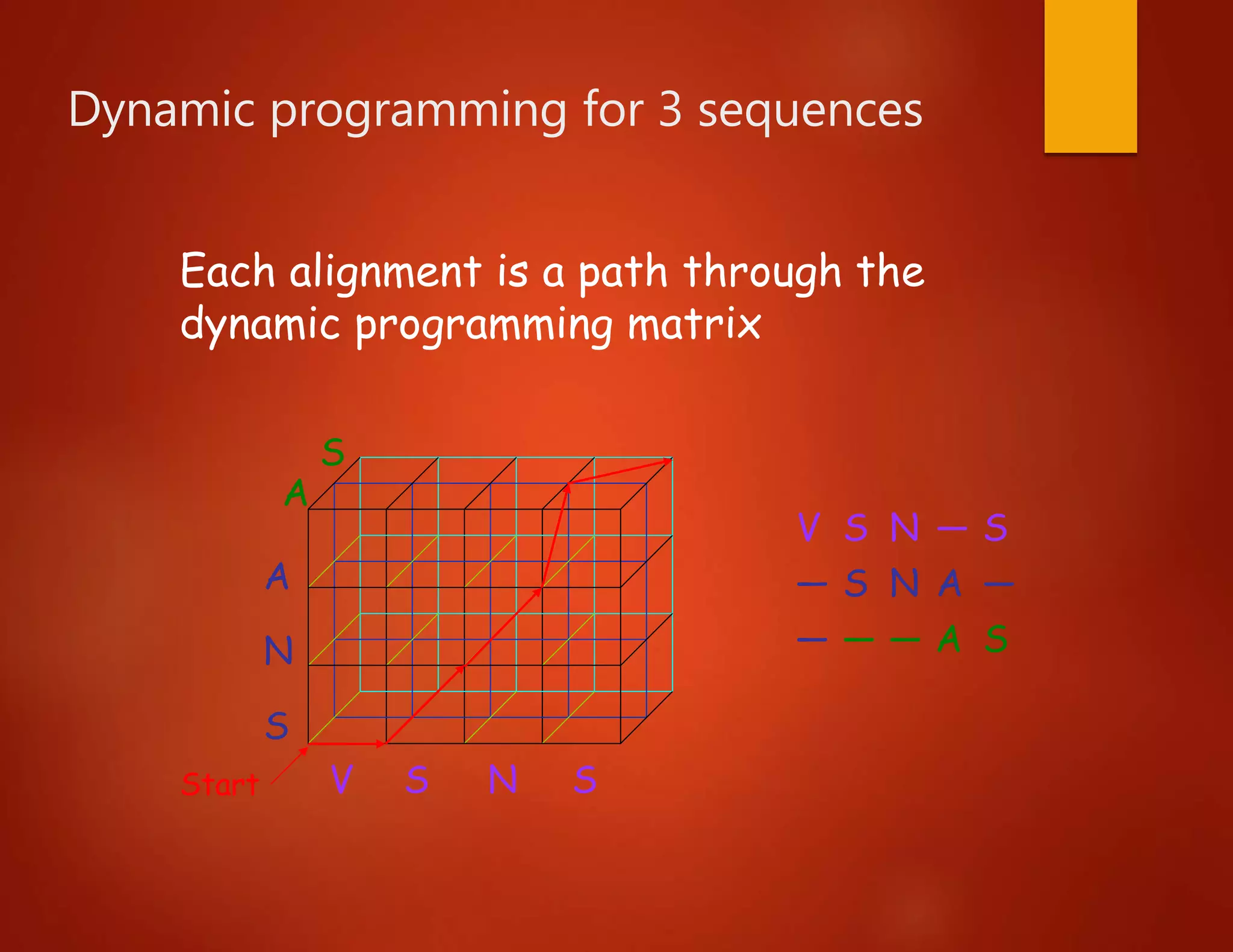

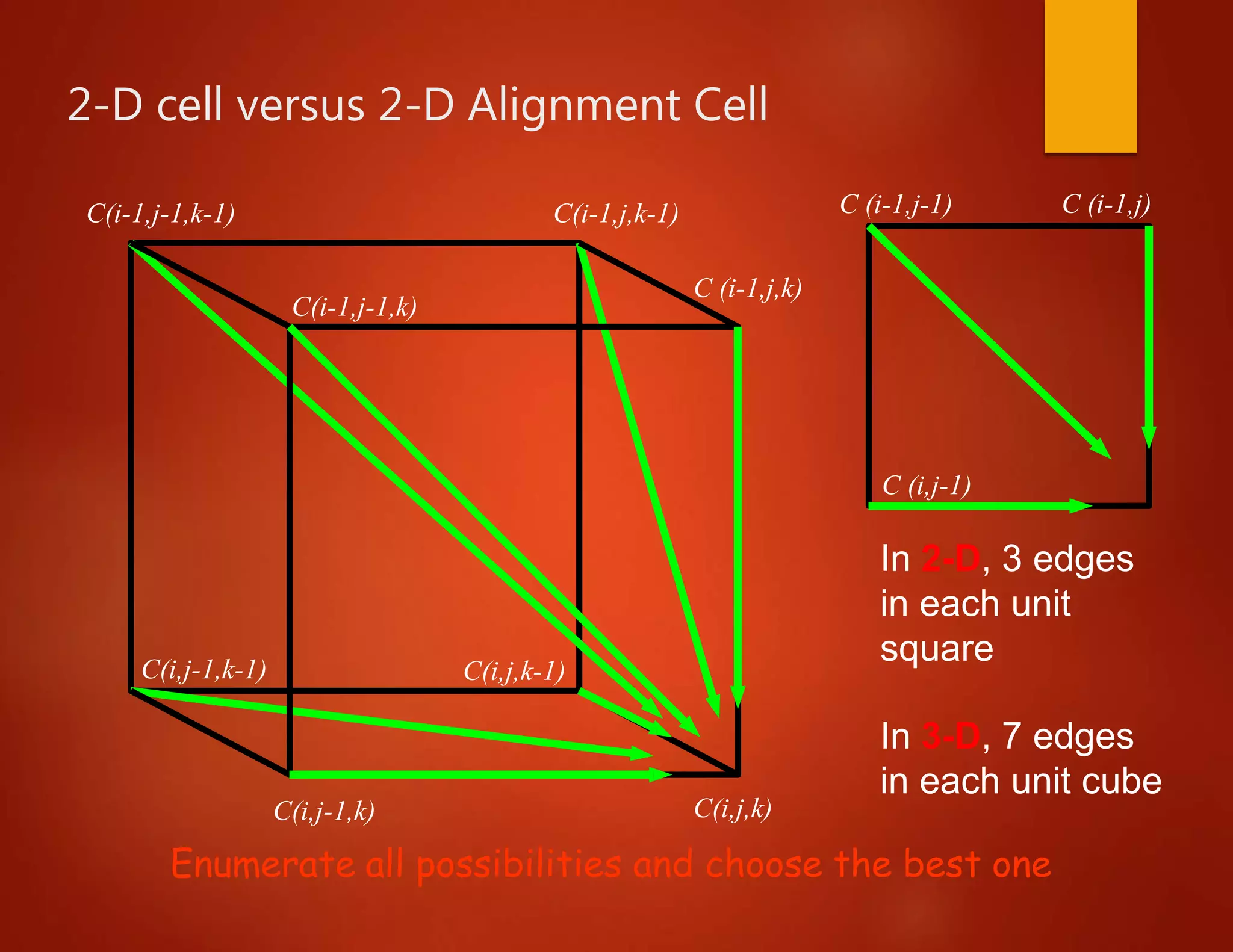

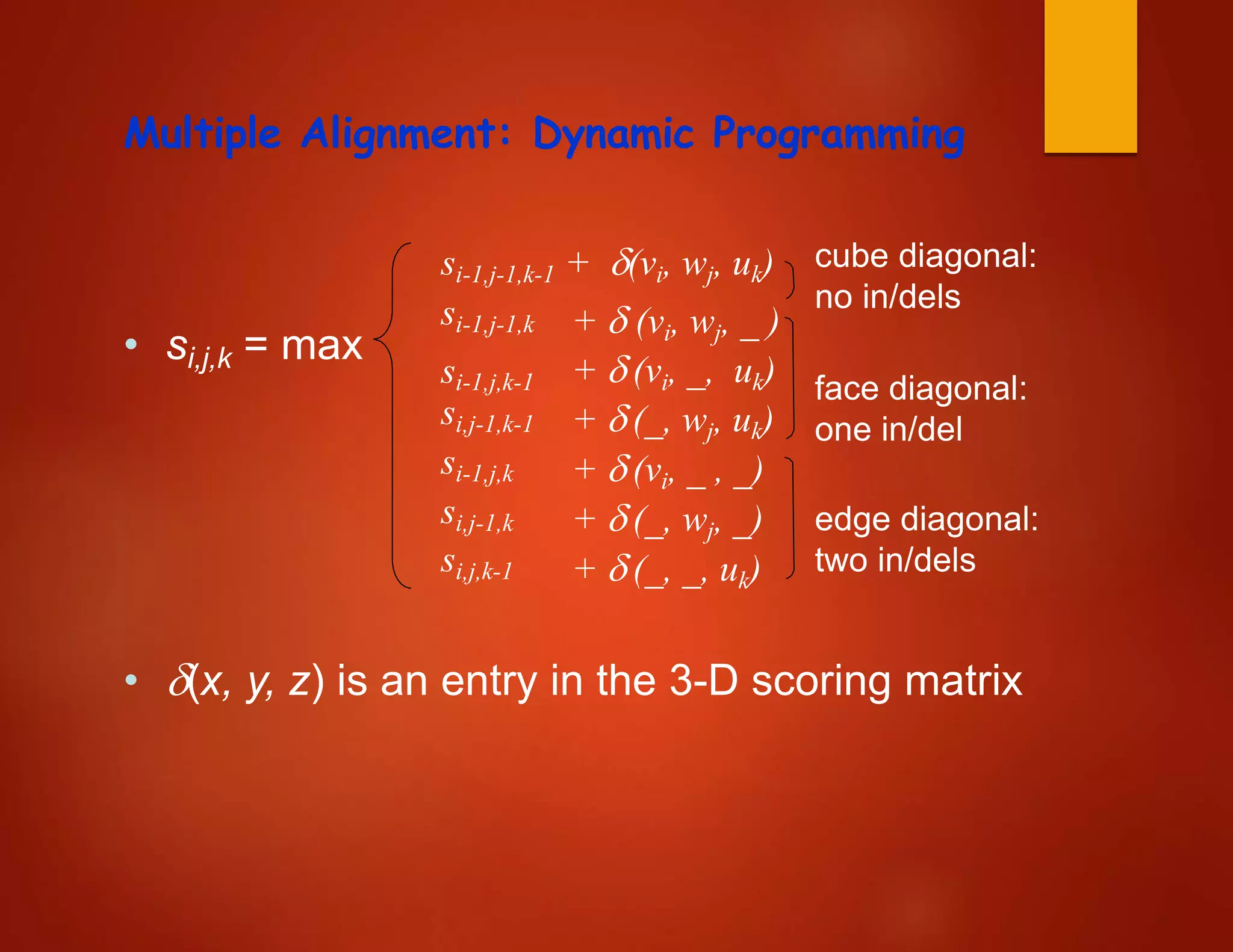

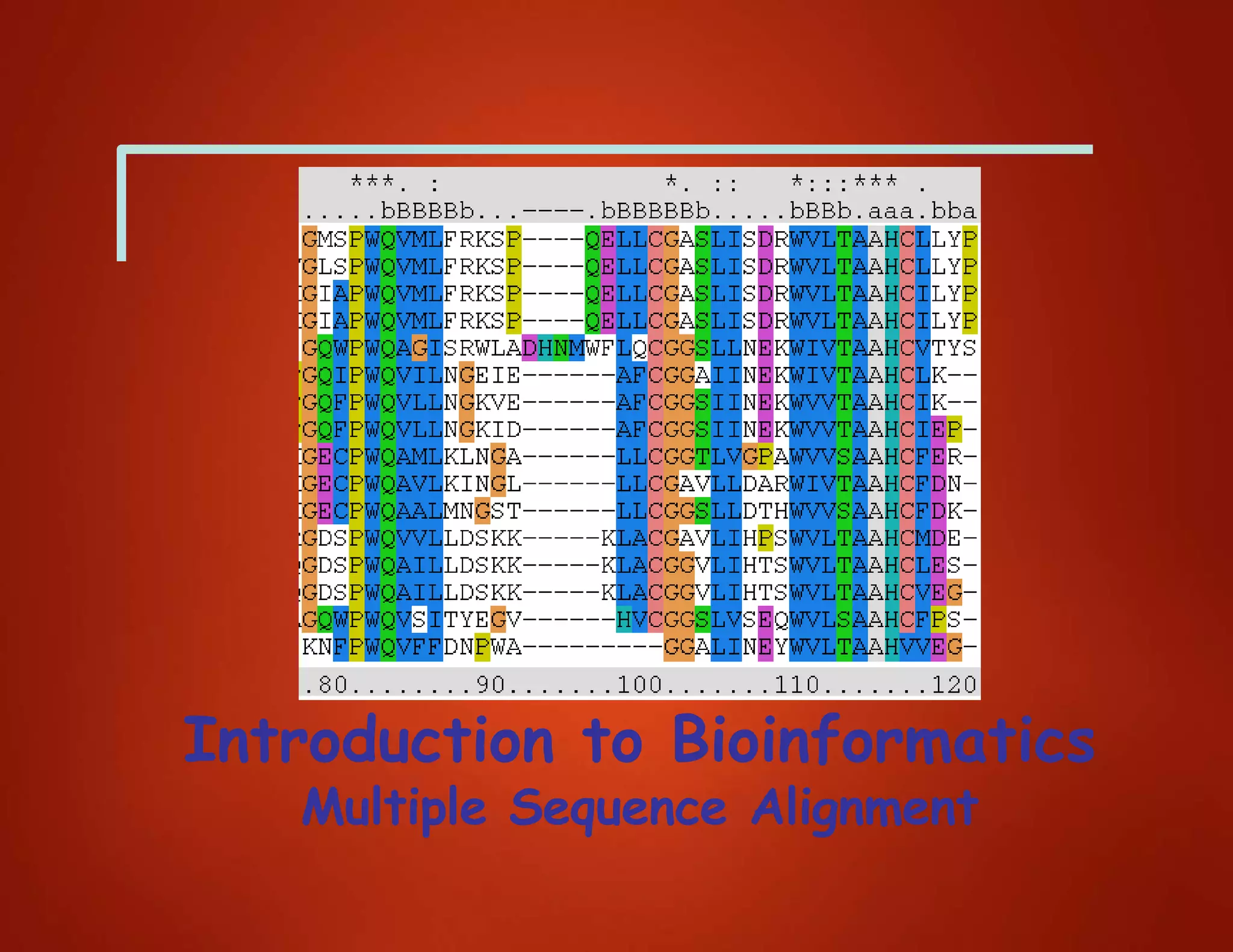

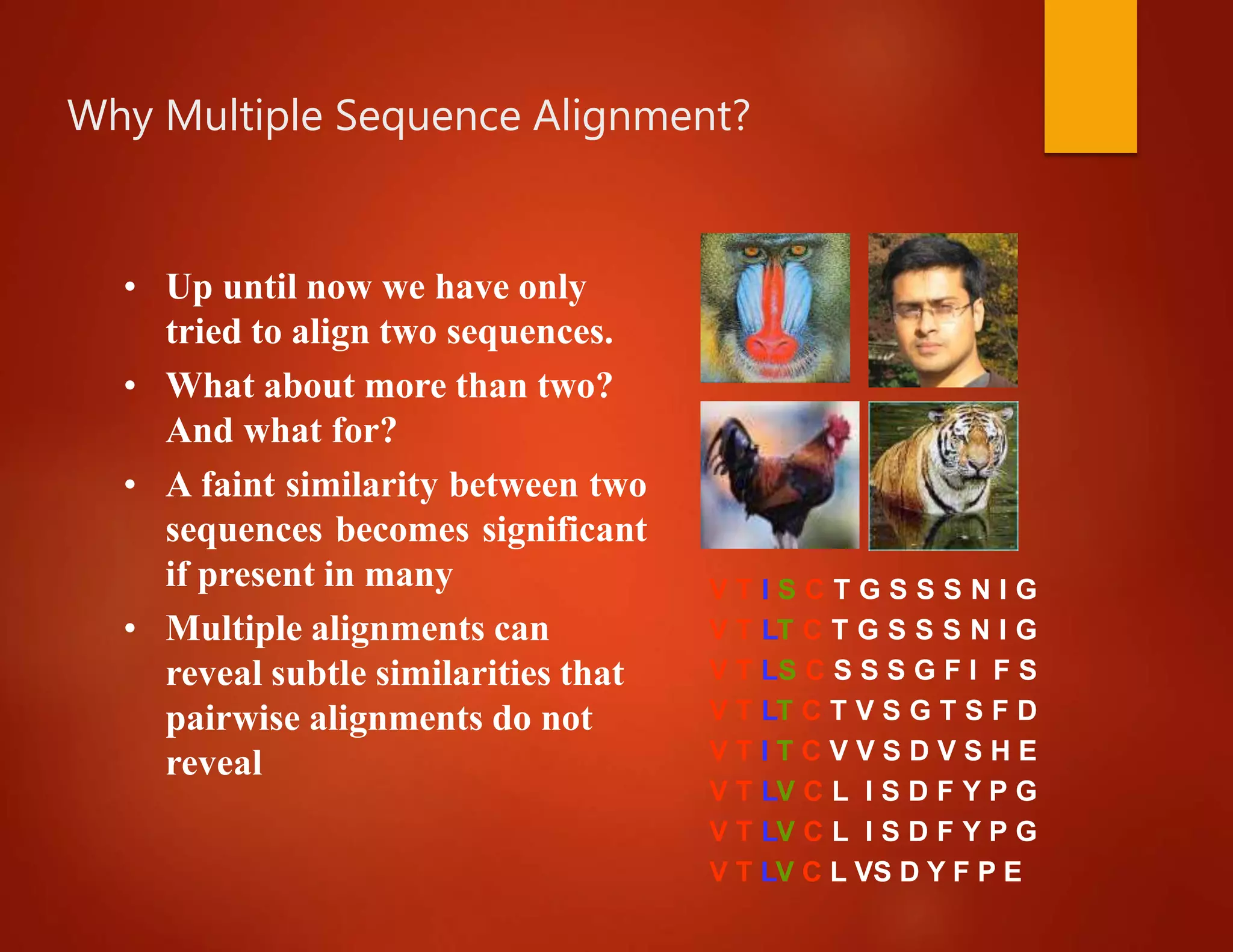

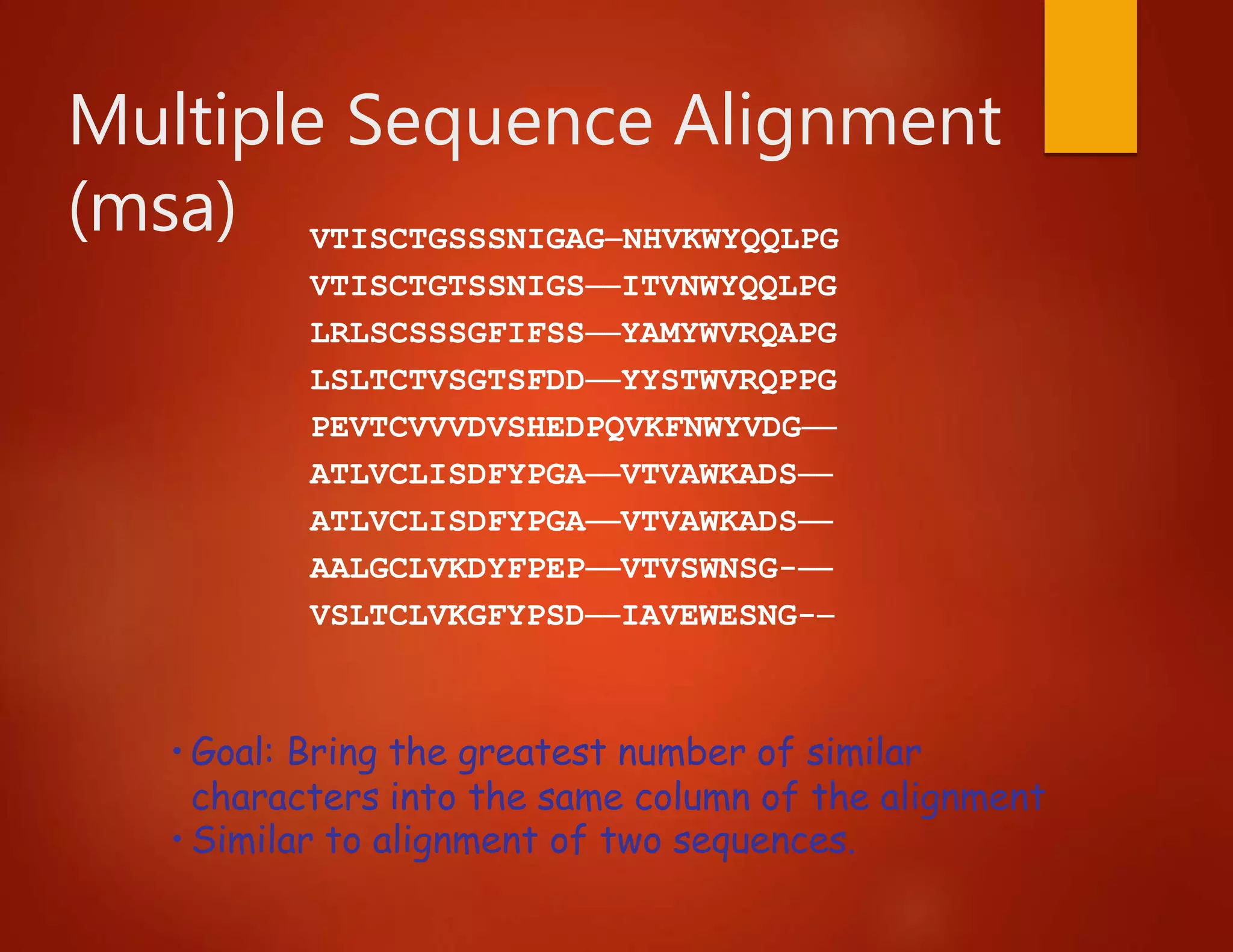

This document discusses multiple sequence alignment (MSA), which involves aligning more than two biological sequences, such as DNA, RNA, or protein sequences. MSA can reveal subtle similarities between sequences that pairwise alignment cannot by identifying conserved regions present in many sequences. The document describes different approaches to MSA, including optimal global alignments using dynamic programming, progressive alignments, and iterative alignments. It notes challenges like computational expense and difficulty of scoring and identifying ancestry relationships with more divergent sequences. The dynamic programming approach to aligning three sequences using a 3D "Manhattan cube" representation is also explained.

![Global msa: Dynamic

Programming

• The two-sequence alignment algorithm (Needleman-

Wunsch) can be generalized to any number of

sequences.

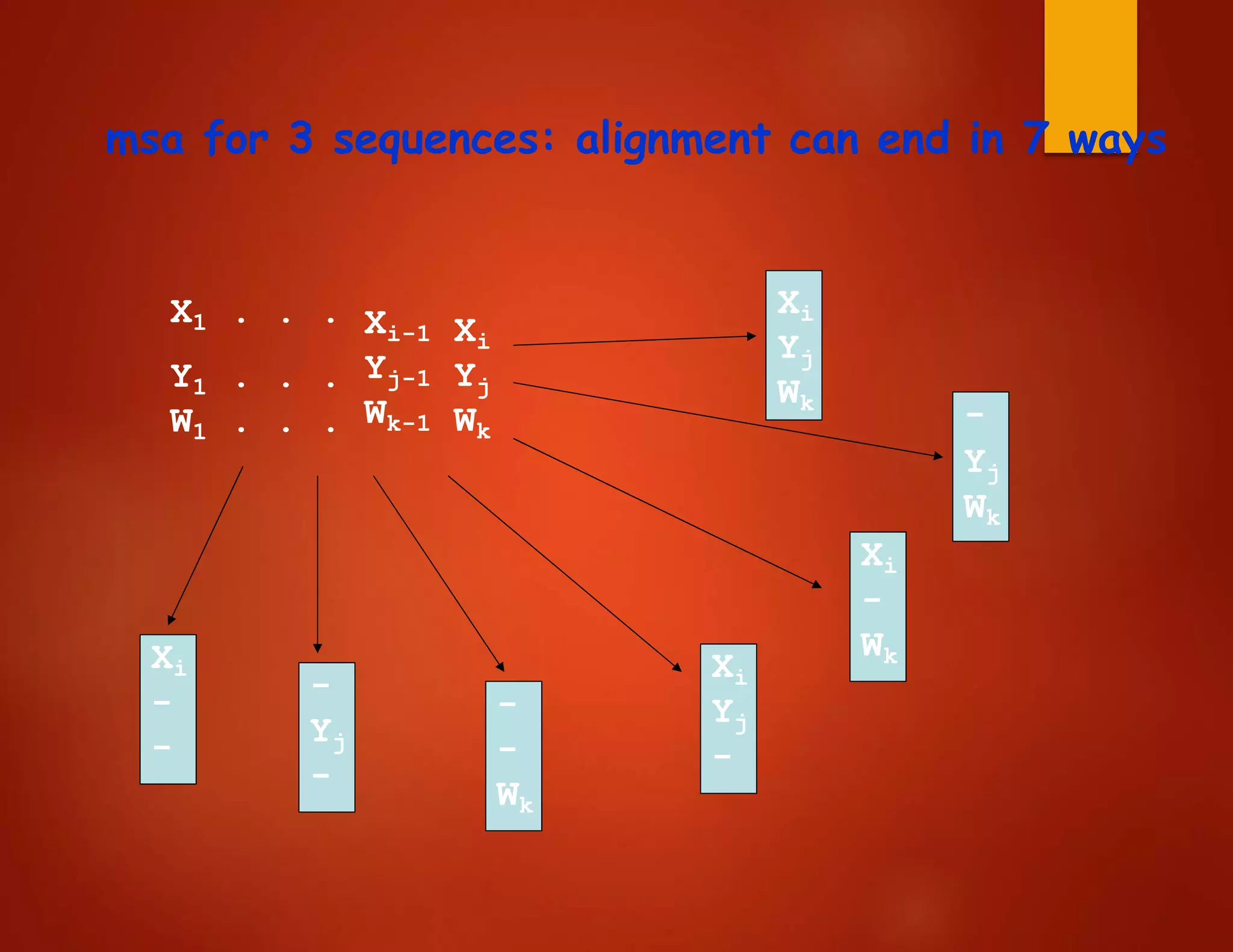

• E.g., for three sequences X, Y, W

define C[i,j,k] = score of optimum

alignment

among X[1..i], Y[1..j], W[1..k]

• As for two sequences, divide possible alignments into

different classes, depending on how they end.

– Devise recurrence relations for C[i,j,k]

– C[i,j,k] is the maximum out of all possibilities](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bioinformatics-lesson05-170427070116/75/Bioinformatics-lesson-7-2048.jpg)