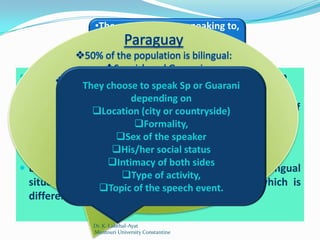

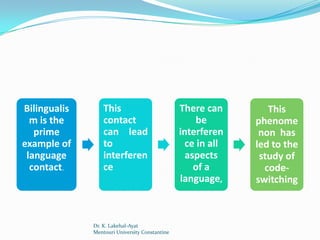

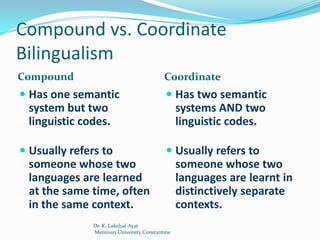

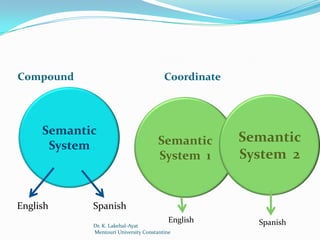

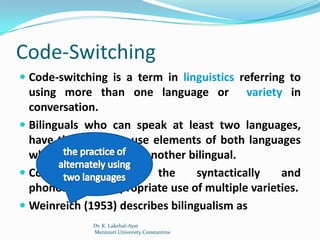

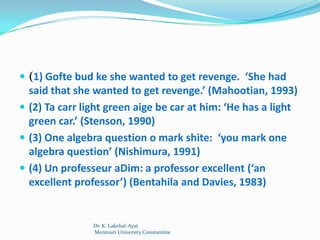

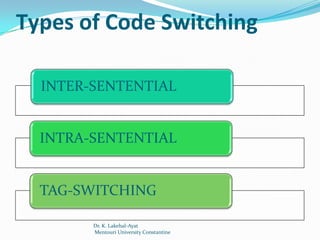

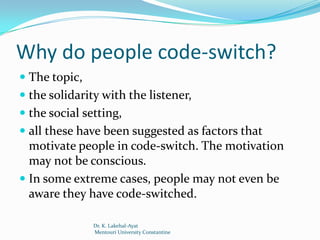

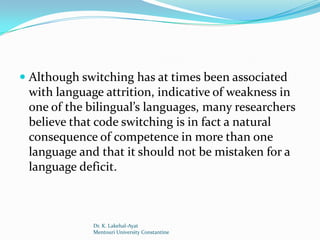

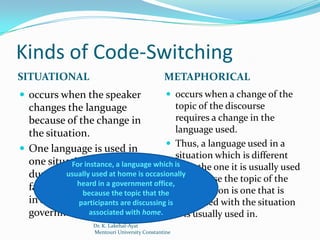

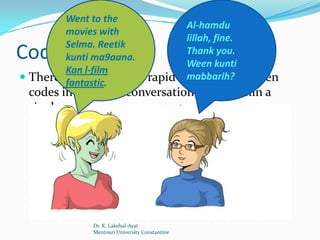

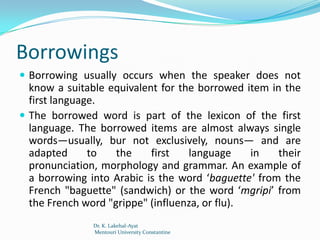

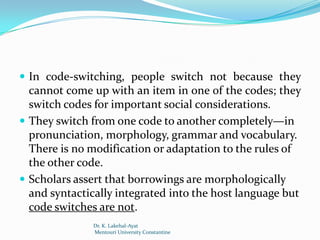

This document discusses various linguistic phenomena that occur in multilingual communities, including bilingualism, code-switching, code-mixing, and borrowings. It provides definitions and examples of each. Bilingualism involves speaking two languages, while code-switching is switching between languages in conversation. Code-mixing involves rapidly switching codes within a single sentence. Borrowings occur when a word is adopted from one language due to no equivalent in the other.