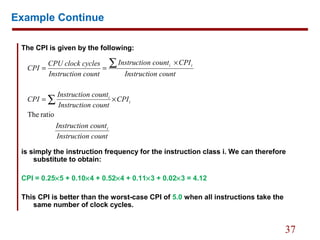

This document provides an overview of implementing a simplified MIPS processor with a memory-reference instructions, arithmetic-logical instructions, and control flow instructions. It discusses:

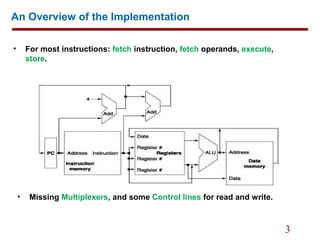

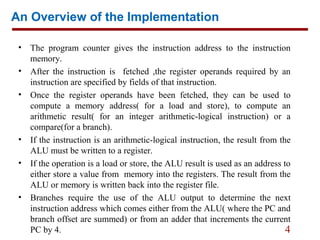

1. Using a program counter to fetch instructions from memory and reading register operands.

2. Executing most instructions via fetching, operand fetching, execution, and storing in a single cycle.

3. Building a datapath with functional units for instruction fetching, ALU operations, memory references, and branches/jumps.

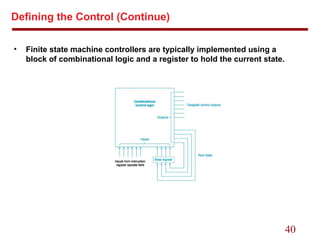

4. Implementing control using a finite state machine that sets multiplexers and control lines based on the instruction.

![27

Breaking the Instruction Execution into Clock Cycles

1. Instruction fetch step

IR <= Memory[PC];

PC <= PC + 4;](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/basicmipsimplementation-170216061215/85/Basic-MIPS-implementation-27-320.jpg)

![28

Breaking the Instruction Execution into Clock Cycles

IR <= Memory[PC];

To do this, we need:

MemRead Assert

IRWrite Assert

IorD 0

-------------------------------

PC <= PC + 4;

ALUSrcA 0

ALUSrcB 01

ALUOp 00 (for add)

PCSource 00

PCWrite set

The increment of the PC and instruction memory access can occur in parallel, how?](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/basicmipsimplementation-170216061215/85/Basic-MIPS-implementation-28-320.jpg)

![29

Breaking the Instruction Execution into Clock Cycles

2. Instruction decode and register fetch step

– Actions that are either applicable to all instructions

– Or are not harmful

A <= Reg[IR[25:21]];

B <= Reg[IR[20:16]];

ALUOut <= PC + (sign-extend(IR[15-0] << 2 );](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/basicmipsimplementation-170216061215/85/Basic-MIPS-implementation-29-320.jpg)

![30

A <= Reg[IR[25:21]];

B <= Reg[IR[20:16]];

Since A and B are

overwritten on every

cycle Done

ALUOut <= PC + (sign-

extend(IR[15-0]<<2);

This requires:

ALUSrcA 0

ALUSrcB 11

ALUOp 00 (for add)

branch target address will

be stored in ALUOut.

The register file access and computation of branch target occur in parallel.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/basicmipsimplementation-170216061215/85/Basic-MIPS-implementation-30-320.jpg)

![31

Breaking the Instruction Execution into Clock Cycles

3. Execution, memory address computation, or branch completion

Memory reference:

ALUOut <= A + sign-extend(IR[15:0]);

Arithmetic-logical instruction:

ALUOut <= A op B;

Branch:

if (A == B) PC <= ALUOut;

Jump:

PC <= { PC[31:28], (IR[25:0], 2’b00) };](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/basicmipsimplementation-170216061215/85/Basic-MIPS-implementation-31-320.jpg)

![32

Memory reference:

ALUOut <= A + sign-extend(IR[15:0]);

ALUSrcA = 1 && ALUSrcB = 10

ALUOp = 00

Arithmetic-logical instruction:

ALUOut <= A op B;

ALUSrcA = 1 && ALUSrcB = 00

ALUOp = 10

Branch:

if (A == B) PC <= ALUOut;

ALUSrcA = 1 && ALUSrcB = 00

ALUOp = 01 (for subtraction)

PCSource = 01

PCWriteCond is asserted

Jump:

PC <= { PC[31:28], (IR[25:0],2’b00) };

PCWrite is asserted

PCSource = 10](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/basicmipsimplementation-170216061215/85/Basic-MIPS-implementation-32-320.jpg)

![33

Breaking the Instruction Execution into Clock Cycles

4. Memory access or R-type instruction completion step

Memory reference:

MDR <= Memory [ALUOut]; ⇒ MemRead, IorD=1

or

Memory [ALUOut] <= B; ⇒ MemWrite, IorD=1

Arithmetic-logical instruction (R-type):

Reg[IR[15:11]] <= ALUOut; ⇒ RegDst=1,RegWrite, MemtoReg=0

5. Memory read completion step

Load:

Reg[IR[20:16]] <= MDR; ⇒ RegDst=0, RegWrite, MemtoReg=1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/basicmipsimplementation-170216061215/85/Basic-MIPS-implementation-33-320.jpg)