Pemphigus vulgaris is an autoimmune blistering disease that affects the skin and mucous membranes. It is caused by autoantibodies that attack desmoglein, a protein that binds epidermal cells together. This causes the epidermal cells to separate from each other (acantholysis) and form fragile blisters that rupture easily, leaving painful erosions. Pemphigus vulgaris is diagnosed through skin biopsy and detection of anti-desmoglein antibodies. Without treatment, it can be fatal due to infection; treatment involves high-dose corticosteroids and other immunosuppressants to control outbreaks and lessen side effects.

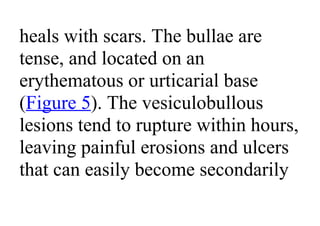

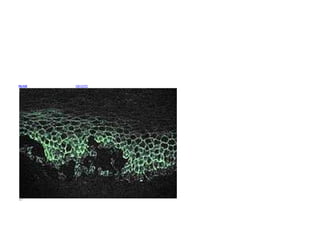

![Microscopic image of direct immunofluorescence

using an anti-IgG antibody. The tissue is skin from a

patient with Pemphigus vulgaris. Note the

intercellular IgG deposits in the epidermis and the

early intraepidermal vesicle caused by acantholysis.

Pemphigus ( /ˈpɛmfɪɡəs/ or /pɛmˈfaɪɡəs/) is a rare

group of blistering autoimmune diseases that affect

the skin and mucous membranes.[1]

In pemphigus, autoantibodies form against

desmoglein. Desmoglein forms the "glue" that

attaches adjacent epidermal cells via attachment](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/autoimmunebullousdermatoses-130625085528-phpapp02/85/Autoimmune-bullous-dermatoses-3-320.jpg)

![points called desmosomes. When autoantibodies

attack desmogleins, the cells become separated from

each other and the epidermis becomes "unglued", a

phenomenon called acantholysis. This causes blisters

that slough off and turn into sores. In some cases,

these blisters can cover a significant area of the skin.[2]

Originally, the cause of this disease was unknown,

and "pemphigus" was used to refer to any blistering

disease of the skin and mucosa. In 1964, a historic

paper that changed the understanding of pemphigus](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/autoimmunebullousdermatoses-130625085528-phpapp02/85/Autoimmune-bullous-dermatoses-4-320.jpg)

![was published.[3][4]

In 1971, an article investigating the

autoimmune nature of this disease was published.[5][6]

Contents

• 1 Types

• 2 Classification

• 3 Diagnosis

• 4 Treatment

•

Types](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/autoimmunebullousdermatoses-130625085528-phpapp02/85/Autoimmune-bullous-dermatoses-5-320.jpg)

![not considered part of the

Pemphigus group of diseases.[7]

Classification

Pemphigus is a group of

autoimmune blistering diseases that

may be classified into the following

types[8]

:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/autoimmunebullousdermatoses-130625085528-phpapp02/85/Autoimmune-bullous-dermatoses-14-320.jpg)

![can affect the eyes and mucous

membrane of the oral cavity.

Intraorally it resembles the more

common diseases lichen planus and

mucous membrane pemphigoid.[9]

Definitive diagnosis requires

examination of a skin or mucous](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/autoimmunebullousdermatoses-130625085528-phpapp02/85/Autoimmune-bullous-dermatoses-19-320.jpg)

![important feature of the disease on

several WWW pages, but is not

mentioned in current Dermatology

textbooks nor do the terms

"Pemphigus" and "cANCA"

produce any hits on a PUBMED

search.[citation needed]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/autoimmunebullousdermatoses-130625085528-phpapp02/85/Autoimmune-bullous-dermatoses-24-320.jpg)

![suppressant CellCept

(Mycophenolic acid) is among

those being used.[10]

Intravenous gamma globulin (IVIG)

may be useful in severe cases,

especially paraneoplastic

pemphigus. Mild cases sometimes](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/autoimmunebullousdermatoses-130625085528-phpapp02/85/Autoimmune-bullous-dermatoses-27-320.jpg)

![respond to the application of topical

steroids. Recently, Rituximab, an

anti-CD20 antibody, was found to

improve otherwise untreatable

severe cases of Pemphigus vulgaris.

[11][12]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/autoimmunebullousdermatoses-130625085528-phpapp02/85/Autoimmune-bullous-dermatoses-28-320.jpg)