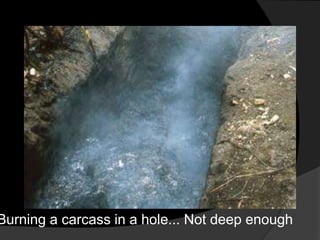

This document provides an overview of anthrax, including its history, epidemiology, causative organism, transmission, clinical manifestations, management, prevention and control. It notes that anthrax is caused by Bacillus anthracis spores and primarily affects herbivores. The most common form is cutaneous anthrax, which presents as a characteristic skin lesion. Treatment involves antibiotics like penicillin. Prevention strategies include vaccinating animals and properly disposing of infected carcasses.