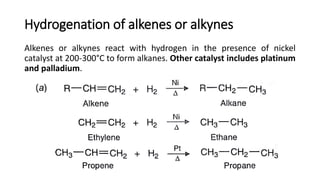

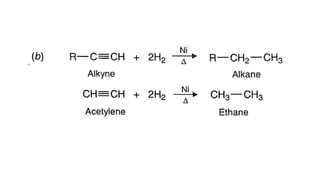

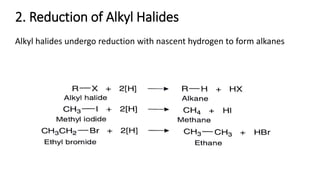

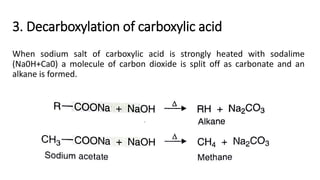

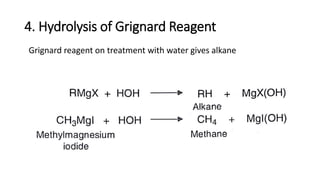

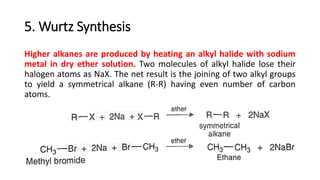

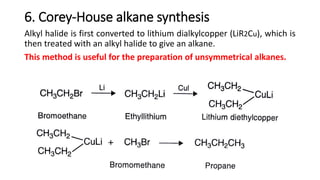

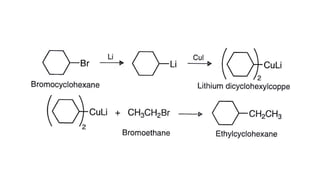

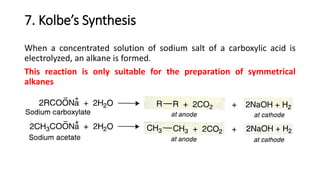

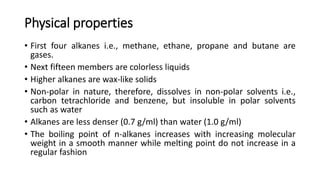

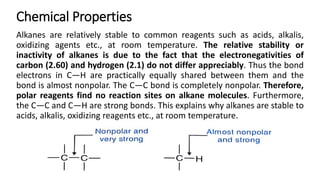

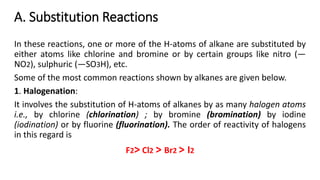

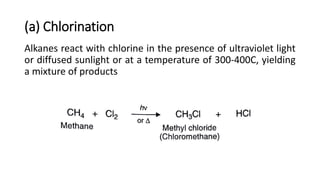

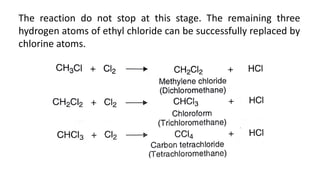

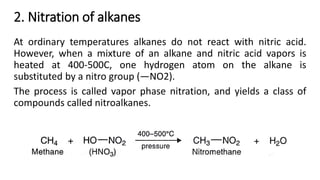

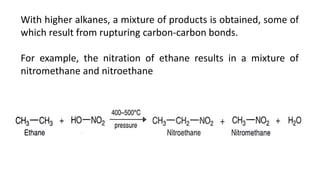

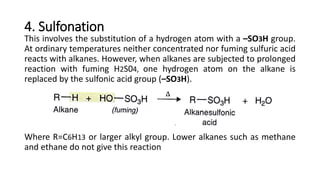

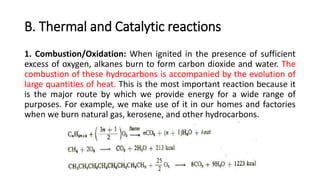

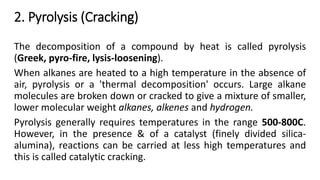

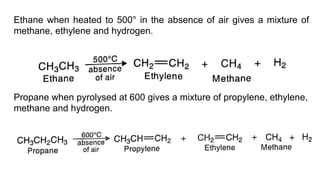

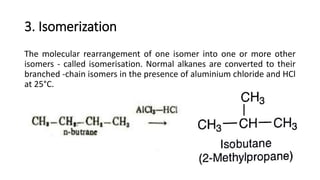

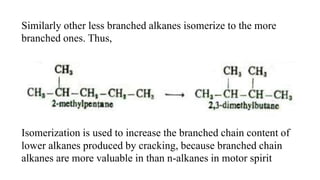

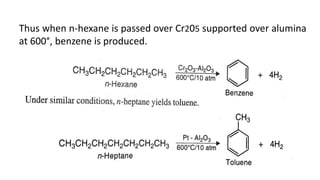

Alkanes can be prepared through several methods including hydrogenation of alkenes/alkynes, reduction of alkyl halides, decarboxylation of carboxylic acids, hydrolysis of Grignard reagents, and Wurtz, Corey-House, and Kolbe syntheses. Alkanes are nonpolar, colorless liquids or solids that are stable under normal conditions but undergo substitution and thermal/catalytic reactions. Substitution reactions include halogenation, nitration, and sulfonation, while thermal reactions include combustion, pyrolysis, isomerization, and aromatization.