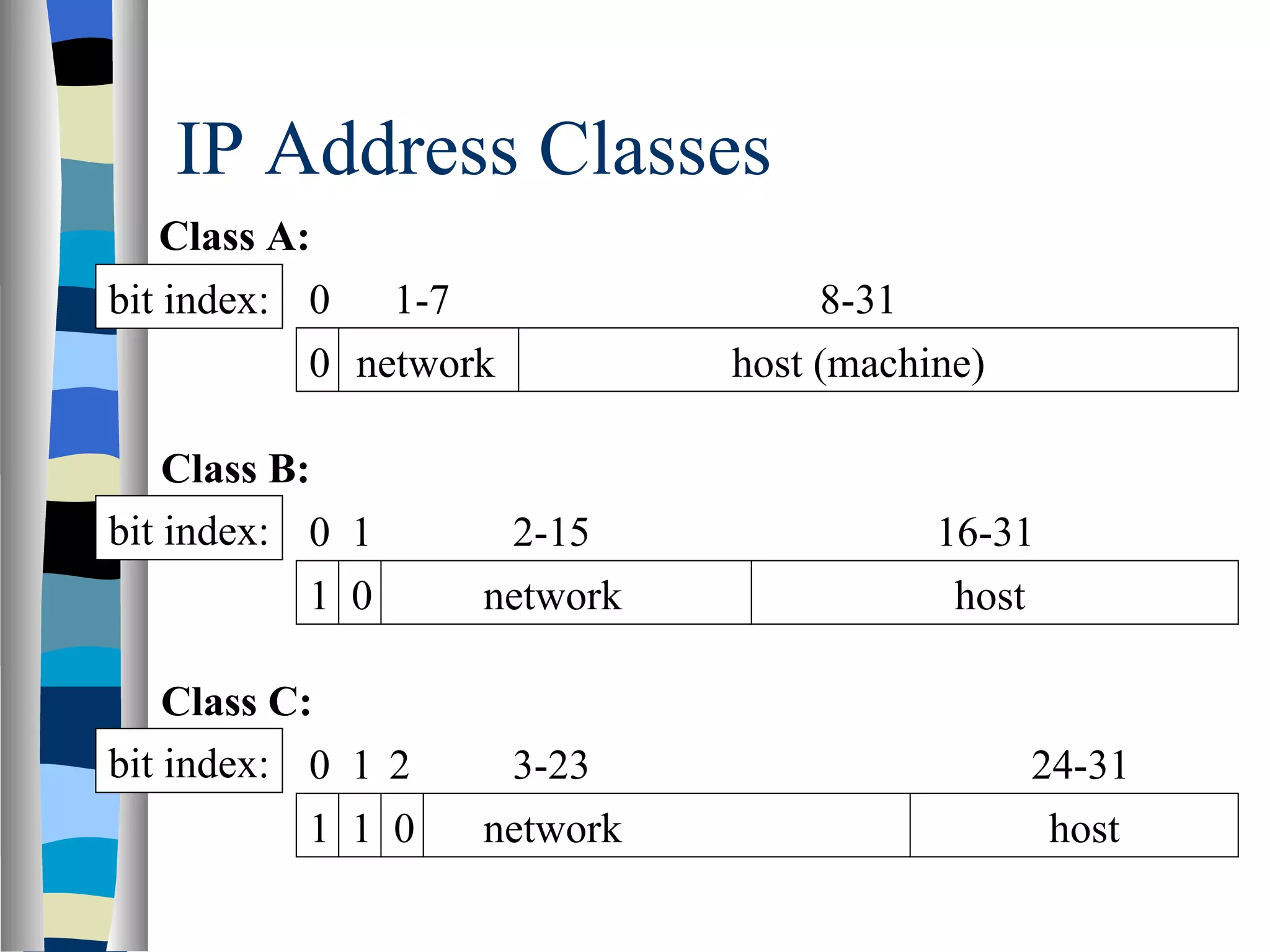

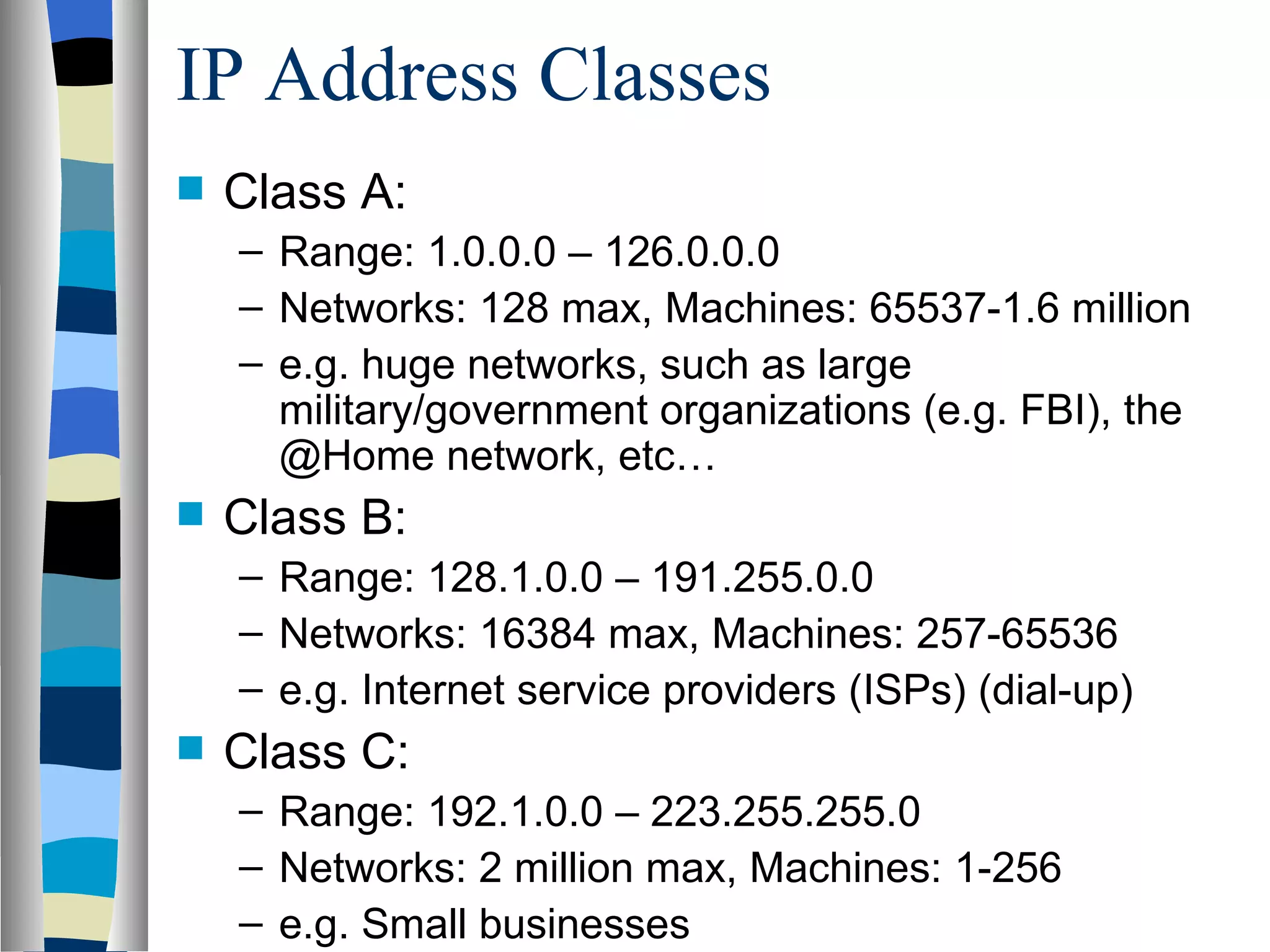

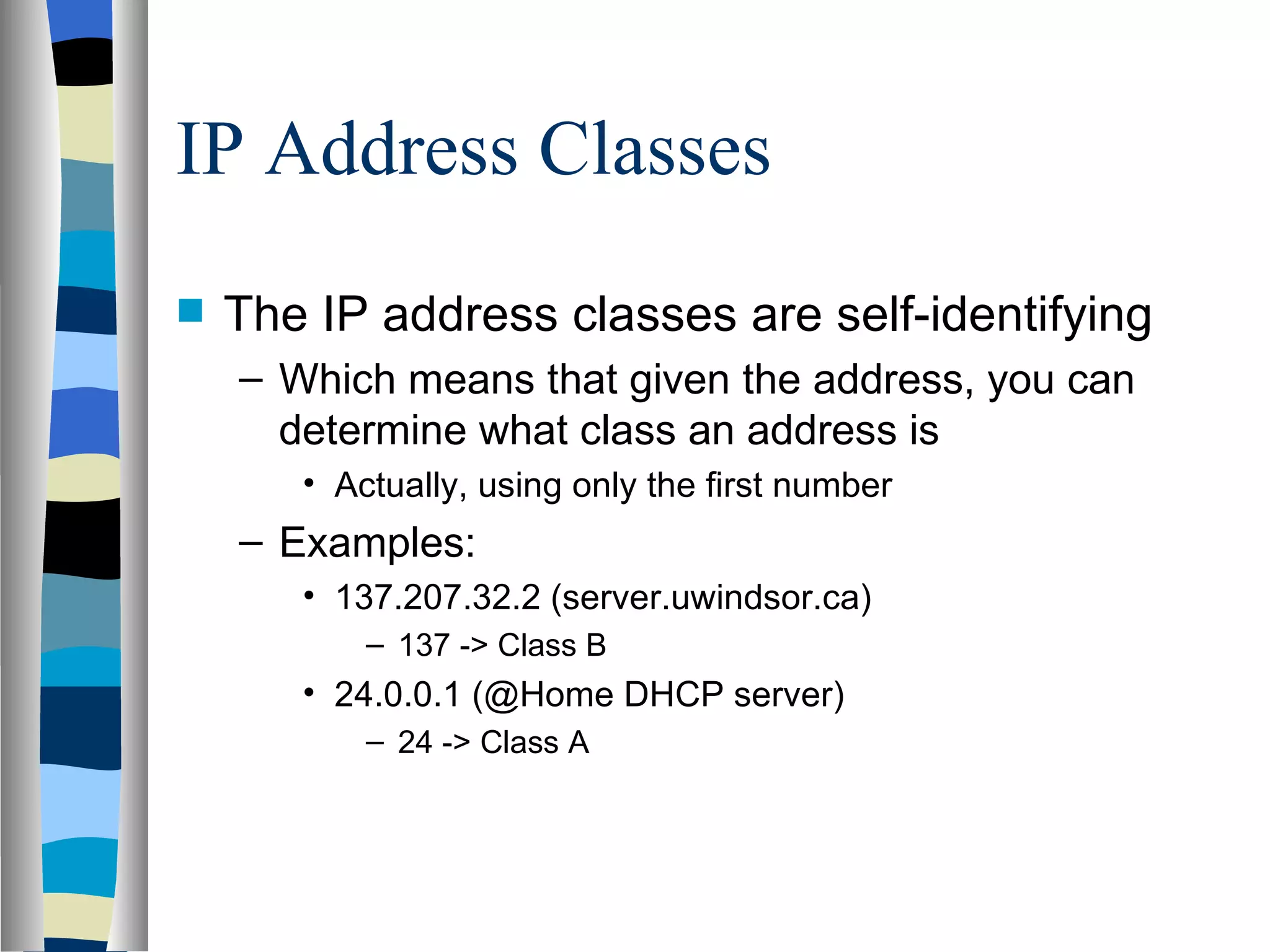

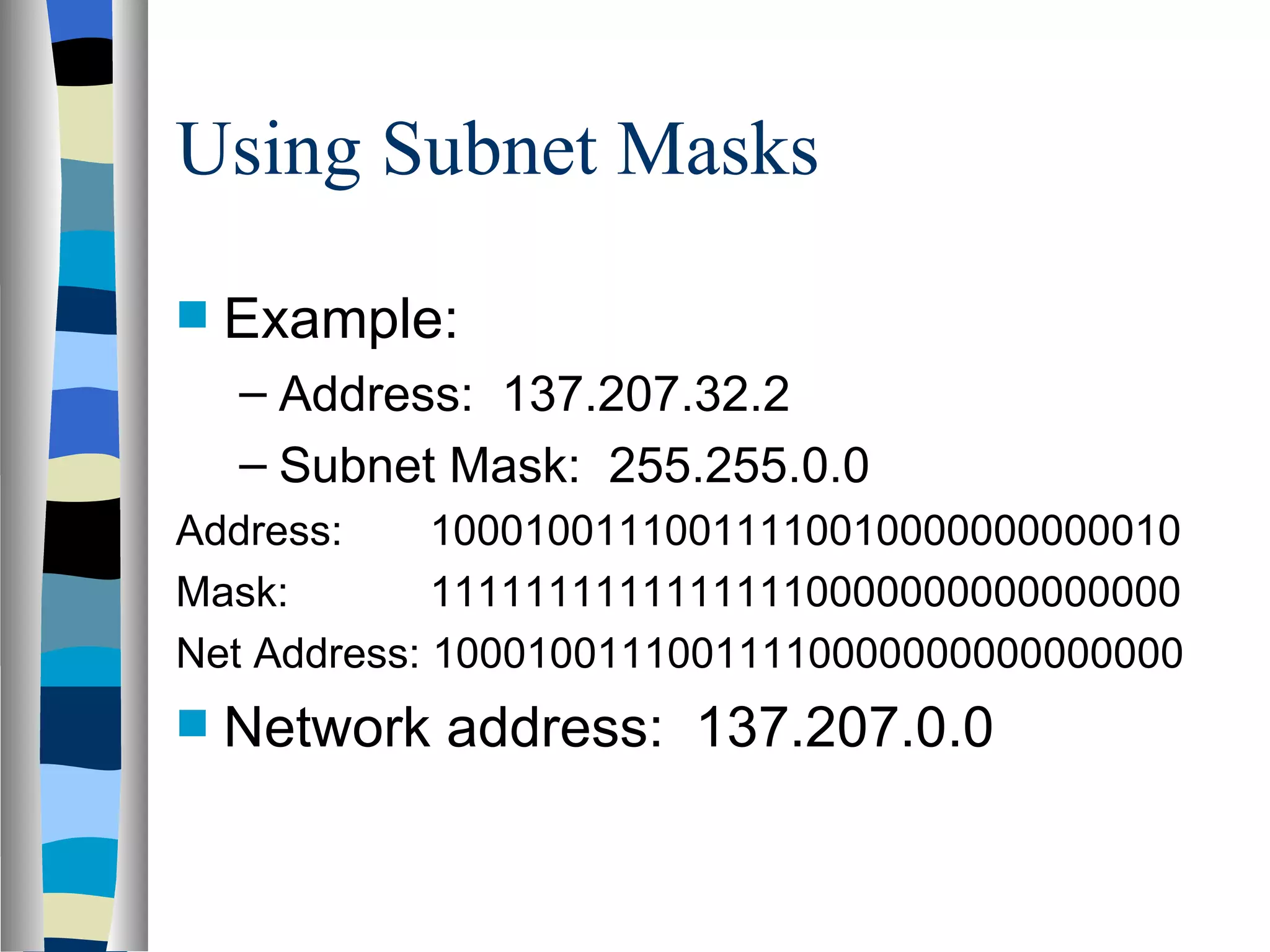

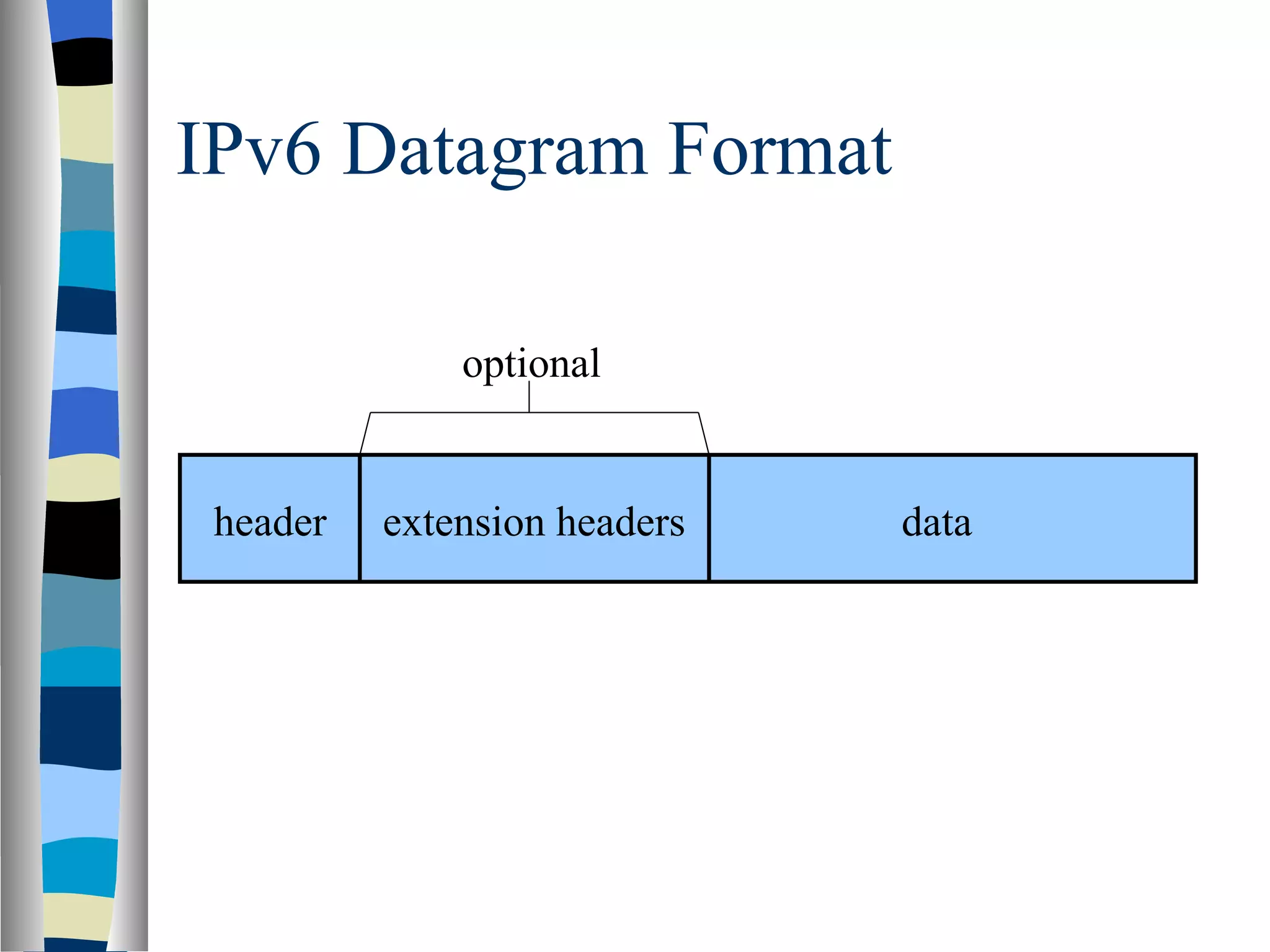

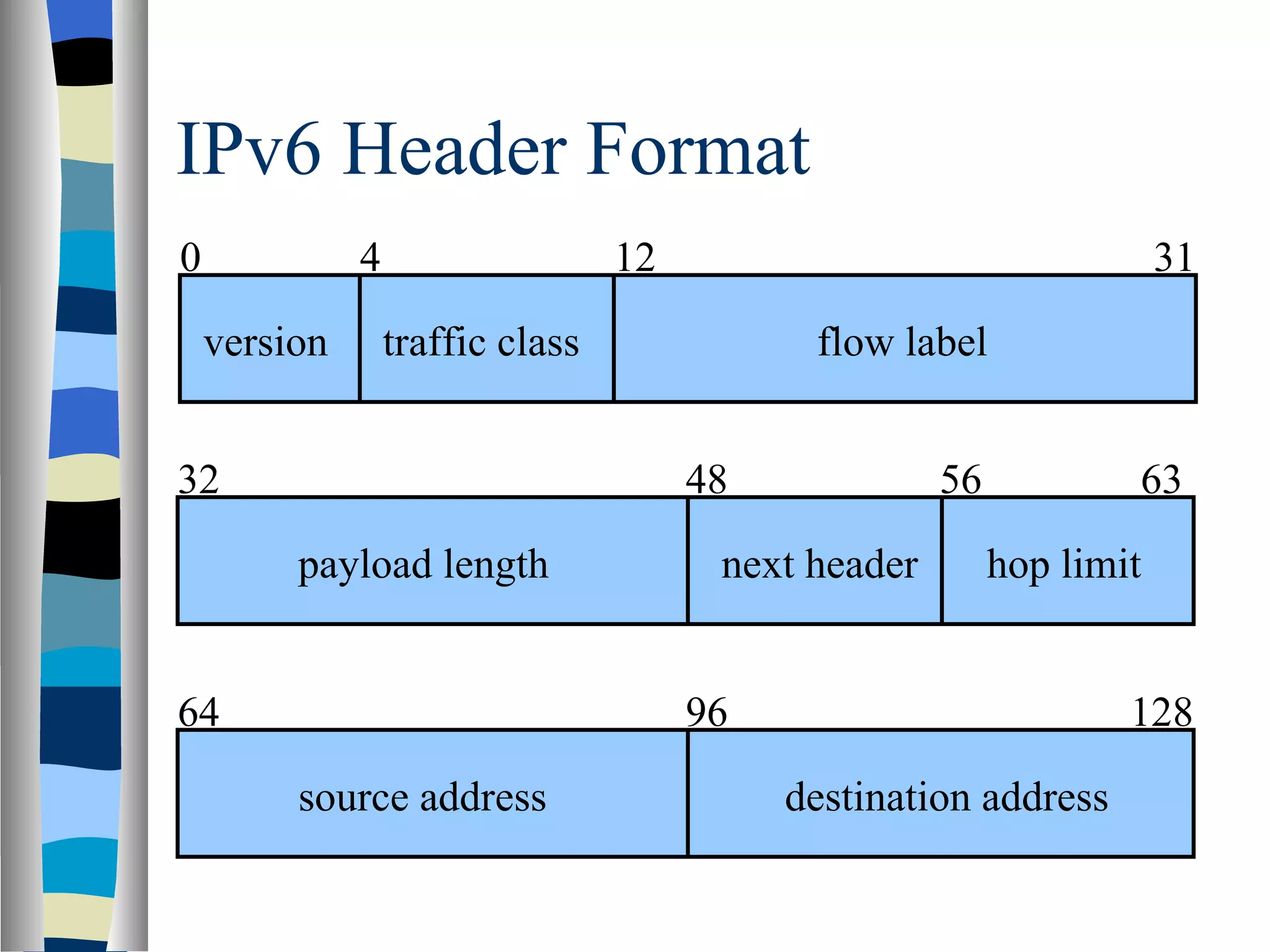

Addressing deals with uniquely identifying the location of an entity for communication purposes. It involves a name/identifier, address, and route. Addresses allow messages to be delivered to the intended destination. IP addresses in IPv4 are 32-bit numbers that identify devices on the network. IPv6 was developed to replace IPv4 and uses 128-bit addresses to overcome the address space limitations of IPv4. A transition approach is needed to integrate IPv6 since the internet cannot be abruptly changed over.